Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Ex-Ambassador David Friedman, who served as U.S. envoy to Israel under former President Donald Trump, is opening The Friedman Center for Peace through Strength at the Simon Wiesenthal Museum of Tolerance in Jerusalem later this week. He sat down with The Media Line’s Felice Friedson in his beautiful home in Jerusalem to share his vision of the center and to reflect on the Abraham Accords and his defining moment as U.S. ambassador to Israel — opening the American Embassy in Jerusalem.

He also shared his perspective regarding Jerusalem and making the city accessible to the Muslim world, saying: “The road to peace runs through Jerusalem.”

Friedman spoke about what he says is the stagnation in the process of signing up more countries to normalize ties with Israel and his take on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the peace process.

The son of a prominent rabbi, Friedman was a corporate attorney before serving as the U.S. Ambassador to Israel from May 2017 to January 2021.

In the last year, he has simultaneously written a memoir on navigating outside the constraints of the political world, titled Sledgehammer: How Breaking with the Past Brought Peace to the Middle East, due to come out on February 8, 2022, and completed a documentary, The Abraham Accords, which will be screened at the gala dinner introducing The Friedman Center and honoring former U.S. Secretary of State Michael Pompeo.

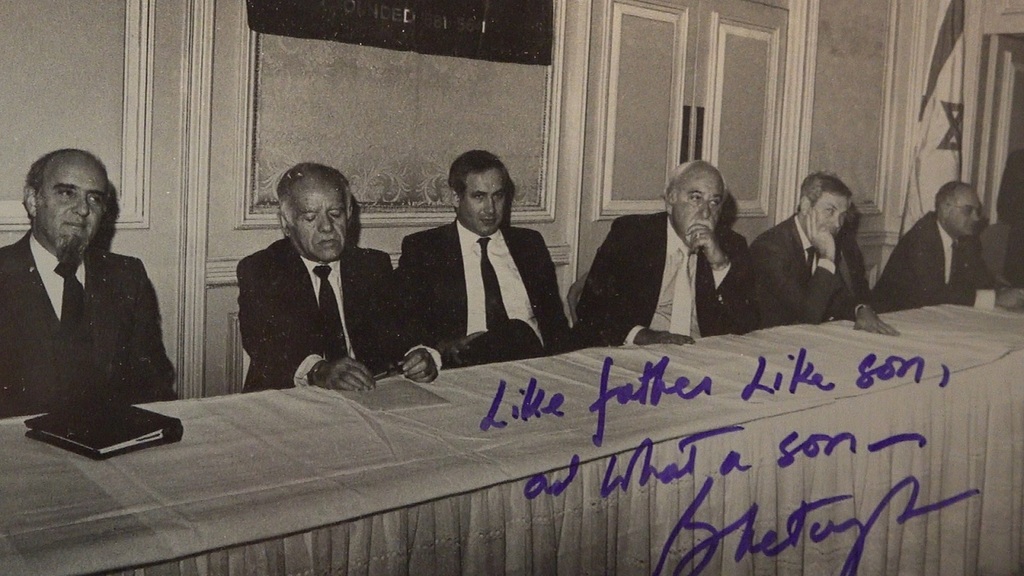

Friedman shared his trophy room, a trove of letters from President Trump, and photos of his father. A photo of his dad with young Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is signed by the former PM: “Like father like son, and what a son!”

The Media Line: Ambassador Friedman, thank you so much for joining me to talk about the unveiling of The Friedman Center.

Ambassador David Friedman: Thanks, Felice! Welcome to my home; our home!

TML: Well, it’s a pleasure to be in your beautiful home.

Friedman: Thank you!

TML: The words “Abraham Accords” are taking their seat in history. There are normalization agreements that have been signed between Israel and the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain. Now you are unveiling The Friedman Center. What was the catalyst?

Friedman: Well, in the documentary that I produced with TBN, I think we settled on one word to describe the catalyst, and that’s trust. We developed over a four-year relationship with Israel and with our allies in the Gulf enormous trust, and I think the best manifestation of that was the extraordinary surprise that the announcements drew on August 13 when we announced the first normalization with the UAE. This is being worked on for a long time and it never leaked, and it never surfaced in a way that could jeopardize the negotiations. And that’s because this was negotiated with a small group of people in Israel, the United States, and the UAE, and Bahrain that trusted each other. And I think that’s really the catalyst.

TML: Did you envision that it would end up where it is today?

Friedman: You know, this was our aspiration from early on. It really began very early on in the administration, just a couple of days after I took my post when President Trump flew to Saudi Arabia and spoke to 50 Arab nations, and then flew directly from Riyadh to Tel Aviv. The first-ever flight from Riyadh to Tel Aviv. The prime minister, at that point, expressed his desire that one day he’d be able to fly from Tel Aviv to Riyadh. Then it just sort of began to move from there.

It began, in the first instance, with America standing with Israel on Jerusalem, on the Golan Heights, on its security on Iran, and then that relationship with Israel grew to a point where other nations that were similarly situated wanted to be inside that circle of trust and that circle of peace. So, it expanded from there, but it really began with unprecedented support for Israel.

8 View gallery

Amb. David Friedman speaks with The Media Line’s Felice Friedson at his home in Jerusalem

(Photo: The Media Line)

TML: On a historical note, your gala event is the first at the Simon Wiesenthal Museum of Tolerance.

Friedman: Yes!

TML: Share. Tell us a little bit about this.

Friedman: Well, you know this is a magnificent building, and I had tours of it throughout its construction phase while I was ambassador. The potential was always apparent. I walked through it last night. We have a spectacular Grand Hall for the dinner, and then we’ll walk across the hall to a 400-seat theater which is really state-of-the-art and spectacular. So, this is a beautiful venue, and I’m really proud to be the first to use it — the first organization to use it. It’s a great honor for me, and I hope that it’s the first of many successes at the Museum of Tolerance. It’s a spectacular building right smack in the center of Jerusalem.

TML: What is the most important element of why you have created The Friedman Center? You have been involved in many things throughout your career — an attorney, and we know you ended up an ambassador with many roles. Why now? Why this?

Friedman: Look, the big goal is to end the Arab-Israeli conflict. I think it’s endable. I think it’s resolvable. I think what we’ve started is going to continue, the pace of which depends upon a lot of factors including support from the U.S. administration, but we are on a glide path, I believe, to end the Israeli-Arab conflict. I want to be a part of it, just a part of it. I mean, there are many, many, many people who contributed to the Abraham Accords. Many organizations have formed that now are seeking to enhance the Abraham Accords, including the Abraham Accords Peace Institute that was begun by my dear friend Jared Kushner.

So, we’re all working in the same direction to get to the same place. My perspective on this is really to focus on Jerusalem. I think that making Jerusalem accessible to the Muslim world to see the care and respect that Israel gives to the Muslim holy sites, or the Christian holy sites, and of course, Jewish. I think seeing that firsthand will go a long way in removing the residual levels of mistrust that exist between the nations or the peoples, more likely, because there have been hundreds of years of false rumors beginning really most significantly in 1929 when the massacre in Hebron began with false accusations on the mosque and it continued through my term as ambassador.

People need to see the mosque. It’s the third holiest site in Islam. There’s 2 billion Muslims out there, and I venture to say that a very tiny, tiny fraction have ever been to Jerusalem. The paradigm for peace that is sort of universally recognized is across from the United Nations on the Isaiah Wall right where “Nation will no longer lift up sword against nation, or study war anymore.” Well, that vision of Isaiah begins with his recipe for how to get to that point of peace. It’s that all of the nations of the world will come to Jerusalem, because Jerusalem is the wellspring of all of their values upon which God will resolve their differences and “Nation will no longer lift up sword against nation.”

So, at least according to Isaiah, who is a prophet respected in all of the major faiths, the road to peace runs through Jerusalem, and in practical terms in the 21st century, I agree. I think that this is such an important place that being able to show that Israel is the right guardian of the religious faiths that are embedded in the Abraham Accords will go a long way to diffusing the forces of extremism, which by the way, I think, are the enemies of the Abraham Accords. That’s what we’re fighting.

8 View gallery

Former PM Benjamin Netanyahu with U.S. Ambassador to Israel David Friedman examining a map of the West Bank

(Photo: U.S. Embassy in Jerusalem)

TML: How do you plan to get that message out? A lot of it is about message.

Friedman: Right! So, messaging is difficult when you don’t have the ability to distribute your message effectively to the audience that you want, which is why, to me, if you look at the peace plan that we wrote in the early part of the administration and released in January of 2020, we have a provision there that speaks directly about Muslim tourism to Jerusalem, which was endorsed at the time by the Israeli government.

I think seeing is believing. I think we live in an environment, in a world today, where words are cheap. They are very cheap currency, but seeing really matters, and so I think that the most important thing is to begin to show the Muslim world that the third holiest site is well taken care of by the Israeli government, and that Israel is the solution, if you will, to many of the problems in the Middle East; not the problem. It’s a solution for respect for human rights, religious tolerance, obviously security, health care, [and] obviously technology. Israel is a solution, and not a problem. I think that message is something that we can generate effectively.

TML: I’m going to have you just elaborate. I’m not going to ask you another question.

Friedman: So, we are going to use the opportunity of being in Jerusalem to meet with as many groups from the United States as we can, and to encourage and meet with as many groups from the region as we can, whether from Egypt or Jordan, or from the Gulf and to really emphasize, I think, the openness and respect that Israel has for the Muslim faith.

I had a very interesting conversation this past summer with the foreign minister of the Emirates, and he said something to me that really resonated. He said that the conflicts of the 21st century are really not between nations. They’re really between ideologies, and primarily between the ideologies of extremism and moderation. And you have that conflict really everywhere in the world. The Emirates has it. Israel has it. The United States has it. We’re trying to empower the forces of moderation.

Religious extremism is a very dangerous form of extremism. We want to try and tamp that down by showing that between the religions, between Christianity, Islam and Judaism, there is no conflict. That, to me, if we can get that message across and reduce whatever conflicts remain — the political conflicts, I think we really have gone a long way to advancing, as I said earlier, the end of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Political differences could be complicated, but they usually get resolved. It’s the religious differences that really are the most challenging and that’s what I think we want to bring an end to.

8 View gallery

Then-US Ambassador to Israel David Friedman visits the home of the family of an Israeli Druze border police officer killed in a shooting attack at the Temple Mount in July 2017.

(Photo: Courtesy)

TML: Not many ambassadors spend their time working their old beat. What’s prompting you to do so?

Friedman: Well, I think my predecessor also stayed on, so I don’t think I’m blazing a new trail here. I’ve had a home in Jerusalem since 2003. I love this city. It speaks to me. I have deep love for Israel, as I do have for America. My greatest love is for the relationship between the two, and I tried to advance that as ambassador. It’s something that motivates me greatly. I have no intention of replacing the role of the ambassador, when he takes over. He’ll be the ambassador, but I want to do what I did before I was ambassador to continue to work on the Israeli-American relationship from a private perspective.

TML: Last week’s inaugural flight of Egypt Air. I think it’s an interesting timing as well. It recalls the post-Oslo Accords period when Israelis flocked to Egypt, but the Egyptians — they never came. So, what’s different now that fuels your belief that a new mutual acceptance in the making?

Friedman: Well, the historical relationships on the one hand between Israel and Egypt, but on the other, Israel and the Gulf, are very, very different. Obviously, Israel was never at war with the Emirates or Bahrain or Morocco or Kosovo in Europe. Sudan, I think, is a more complicated example. It’s all the more important that Sudan normalized as well. You can see the warmth between the countries. It’s not one way. A lot of the travel is restricted now by COVID, so the rules change almost monthly on travel.

When I was in the UAE and Bahrain, I found the people there who warmly welcomed the Israelis, and there are both Emiratis and Bahrainis that are here, and they are here [in Israel] now. There’s a group that I was going to speak with this morning. The plans got a little bit complicated, but there are groups that come here, and there will be more. When COVID is over, you’ll see significant (numbers of) groups coming.

TML: So, I brought up Egypt which has had a cold peace [with Israel]. Do you feel that the Abraham Accords helped to shift the paradigm here? What is going on?

Friedman: I think that the Abraham Accords will bleed into Egypt and Jordan as well. I think it was an icebreaker that resonates throughout the Arab world. So, as to Egypt and Jordan, which already had peace agreements with Israel, those will become warmer. As to the countries that normalized, that will grow tremendously. As to the countries that have not yet normalized, I think they will. So, I think it’s just going to expand in all of those directions. I wish I had a better sense of the timing. I know what the timing would have been had we remained in office. It would have continued to grow rapidly, but I still think it’s going to grow.

TML: Saudi Arabia is an interesting, different country, because when you look at what’s happening, they are having meetings with Iran. It’s raising flags in terms of what does that mean, and yet there’s a sense to want to somehow do business with Saudi Arabia. We also know that business is even done with Israel behind the scenes. What’s your take on it?

Friedman: Well, Saudi Arabia is right across the Strait of Hormuz from Iran, and it’s a significant issue for them, and when they feel insecure in the sense that they don’t see the United States standing up strongly against Iran, they have to come up with a Plan B. So, I think a lot of those discussions are the Plan B. It’s really an inferior plan to Plan A, which is to unite resolutely against the Islamic Republic of Iran and to weaken them to the point where we can make a good deal rather than a bad deal, but that’s not their perception right now. And I think they’re accurate.

There is a perception in Saudi Arabia, and all around the world, all of America’s allies are looking at America now and scratching their heads and trying to figure out what is the new foreign policy at large. How strong a leader will America be on the world stage? If people perceive America as retreating into a more insular role in the world, they are all going to be looking for other ways to protect themselves. It’s only natural, but it’s unfortunate, because a strong American and a strong Israel coupled with other strong allies, I believe is the only way to make this world a safer place.

TML: On that score, in recent days the House Foreign Affairs and Senate Foreign Relations Committees have through an overwhelmingly bipartisan voice sent their respective versions of the Normalization Act to be voted upon. It’s not just a resolution saying “very nice” but it’s going to become a law requiring the American government, and the State Department in particular, to strengthen and expand the achievements of the Abraham Accords. It’s quite a tribute to something very few saw coming. Looking back on your tenure as US ambassador to Israel, does it get any better than that?

Friedman: Probably not. It was the highlight, certainly, of the work we did. It was a vindication of a strategy that we had from the beginning which was that the Arab-Israeli conflict was not as insoluble as people thought. That the desire of Israel and the Arab nations to become closer to each other was palpable, and that we did not risk that process by standing with Israel. In fact, by standing strongly with Israel, and at the same time signaling that we would stand resolutely with Arab nations who joined us in good faith, I think we sent the right message which ultimately history has borne out that we made the right call, and it’s very gratifying of course.

TML: In the early days of the Biden Administration, some feared the new team would try to throw out the Abraham Accords along with some other Trump signature pieces. Word circulated that the title itself would not be used. What were the elements of the Abraham Accords that were so strong that they could survive even the most rancorous transitions of government in history today?

Friedman: Well, I think that the whole phrase “peace in the Middle East” is sort of like used in the context of a royal flush, or an inside straight, or a total eclipse of the sun. I mean, these things just don’t happen [frequently], so when they do, I think that people from around the spectrum of politics embrace them. The refusal to use the phrase earlier on I think was just pettiness, and I think that the Biden administration realized that that was really unpopular and petty, and ultimately now we all use the phrase Abraham Accords. I think it has become socialized into the vernacular of the Biden administration.

But let’s face it, there hadn’t been a peace agreement between Israel and an Arab state since 1994. We achieved five normalization agreements with five Muslim countries — if you include Kosovo within a period of four months, and that momentum needs to be nurtured. I don’t know anybody, frankly, who is against the Abraham Accords. I mean, in a world that is so hyper-partisan, and so hyper-political, the fact that Americans on both sides of the aisle, I think Europeans, I think of all the traditional critics of Israel, I think they are still in favor of the Abraham Accords, with the exception of the small groups that I don’t think anybody expects to act alongside the United States.

TML: The Biden administration wants to increase the number of countries that have signed normalization acts with the State of Israel. Why do you think it has taken a bit of a hiatus? There is a lull right now.

Friedman: Because ultimately, the Abraham Accords deals are all bilateral agreements between Israel and an Arab country, with the United States standing strongly behind both of them. That strength can be manifested in different ways, whether it’s from a security perspective, or an economic perspective, or a political perspective, each one of these deals has their own characteristics. But they all begin with a strong United States taking a bold position on the world stage, and whether you are looking at Afghanistan, or you’re looking at Iran, these countries now have reason to doubt whether that’s the approach that the United States will take in the future.

I think if that gets reversed, I mean, if America returns to its position of strength, that will be the switch that needs to be turned in order to revitalize more Abraham Accords deals.

TML: You’ve been quoted as talking about when it comes to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the train is leaving. You have stated that in the past to me as well. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is on hold for numerous reasons. Do you think despite this that the Abraham Accords will continue no matter what, and that the Palestinians are still kind of sitting in a state of not knowing where to go? What is really happening from your perspective?

Friedman: Look, I think what happened is it’s been a dose of realism for the Palestinians. They don’t have a veto on progress. They don’t have a veto on peace. At the same time, I think all of the nations that we’ve dealt with would like to see progress made on the Israeli-Palestinian front. They view it, I think as I said earlier, as a political issue. They want to continue to discuss it as a political issue, but they don’t see that political issue as being a bar to progress — bilateral progress — between Israel and the particular Arab nation. So, what the Palestinians I think need to understand is that people would like to help them. People would like to see a political resolution, but they need to sort of get off the idea that they can continue to threaten and coerce the nations of the world to stop acting in their own interests waiting for them to become more realistic.

TML: In speaking to many Saudis, which I do, many feel that the whole issue of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has to be solved first, and then they will move forward with a normalization status. Do you feel that there is sort of two versions of this happening, that some things are said on a private level, as opposed to on a diplomatic level?

Friedman: Yes.

TML: Critiques of Prime Minister Naftali Bennett accused him of omitting the Palestinian issue when he spoke at the United Nations last week. Did the Trump years create a pathway to the region through the Gulf states and without peace with the Palestinians?

Friedman: Well, I think that what we have is incremental peace in the region, but not yet peace with the Palestinians. They don’t come at the exclusion of each other. We’ve made incremental massive steps forward, but we still have a way to go, and I think that there’s huge problems with the Palestinian leadership. I think that, obviously, half of the Palestinians live under the control of Hamas. The PA has more problems than we have time to talk about, so there are leadership issues there that have to get sorted out in a way that enables discussion. The difference between now and the past is that that blockage doesn’t keep everybody else from continuing to do what they think is in their own best interest.

TML: Moving the United States Embassy to Jerusalem, it was supposed to be cataclysmic and, interestingly enough, also the American recognition of Israeli sovereignty over Jerusalem and the Golan Heights. Why wasn’t it?

Friedman: Because the reality is that everybody knew that Jerusalem is the capital of Israel. Everybody knew because that’s where the prime minister is located, where the president is located, where the Knesset is located, where the Supreme Court is located. It’s the city that the United States voted overwhelmingly, going back to 1995, to recognize as the capital of Israel.

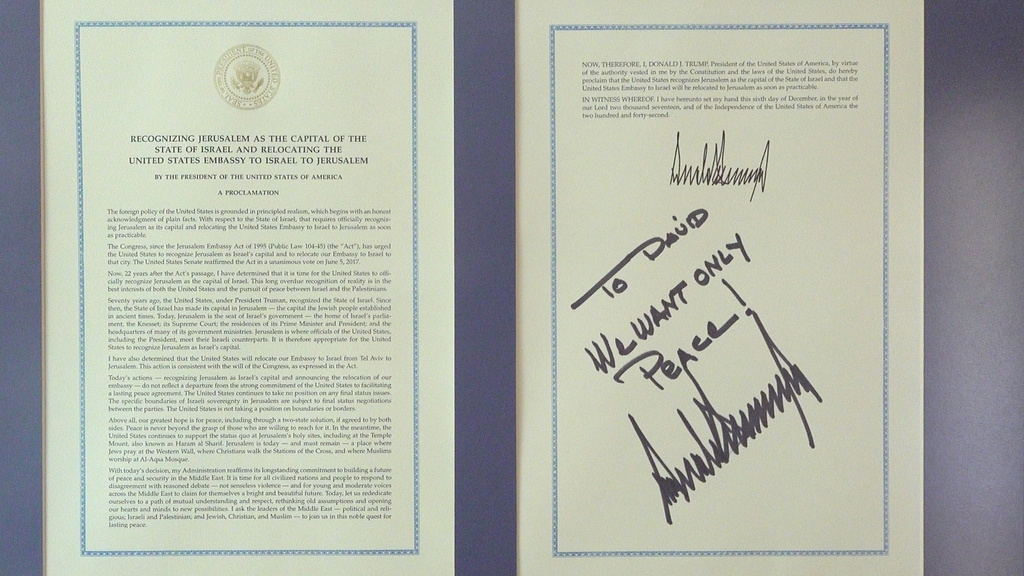

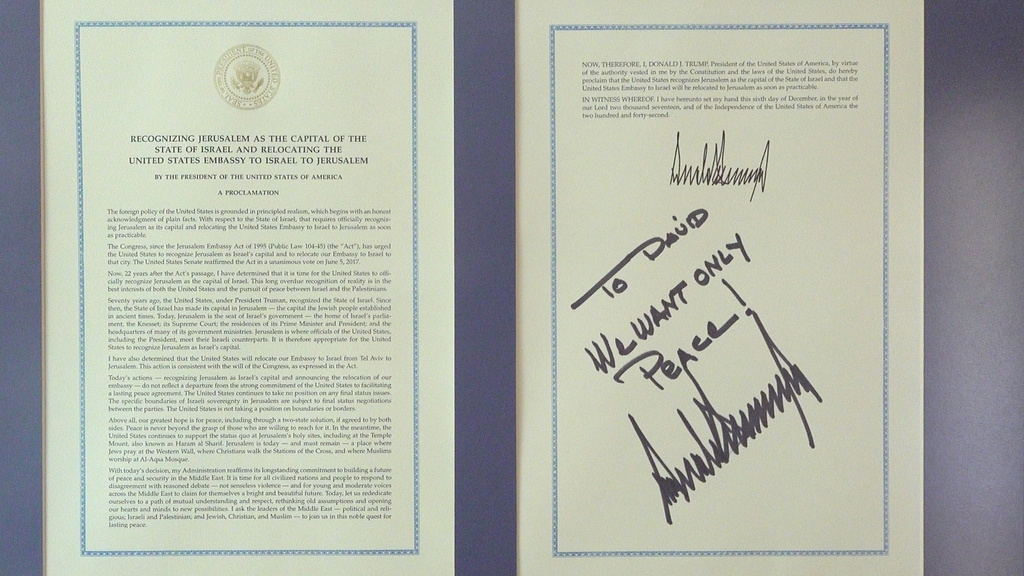

8 View gallery

Proclamation signed by former U.S. President Donald Trump recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and declaring the U.S.’s intention to move the embassy to the city

(Photo: Courtesy)

It’s just when you do something that everybody knows is true and everybody expects will happen one day, it’s just not as big a deal as people would expect. This issue would be studied very, very closely, and we took extraordinary precautions just to be safe, and not, God forbid, to be sorry. But a lot of us thought that this would go forward without any cataclysmic actions. The same thing with the Golan Heights. I mean, who had a better claim to the Golan Heights? [Syrian President] Bashar Assad who gasses his own people? Who the United States targeted with 70-some odd Tomahawk missiles after he used chemical weapons on his own people. I mean, this is not a meaningful debate as to whether Israel should keep the Golan Heights which it needs critically for its own security, which it has the better claim relative to Syria. So, at the end of the day, these types of diplomatic issues were held in abeyance by a lot of petrified politicians who just did not want to touch the status quo. We weren’t afraid of changing the status quo. We were convinced it was good for Israel, and good for the region, and would not result in violence, and that was our approach.

TML: Ambassador Friedman, is there one single achievement that you think defines your legacy?

Friedman: Well, I would say moving the embassy to Jerusalem. I would say that is something which I set as my goal before I took office. If you go back and look at the press release, I think it was on December 15th of 2016 that I announced my appointment, that I announced my nomination, I was quoted as saying, “I hope to be working out of a US Embassy in Jerusalem.”

That was certainly the goal that I set for myself to work on. Not to the exclusion of everything else, but that was important.

I also think that its effect was enormously important to the Trump administration’s foreign policy, which shows that the president is willing to stand with his allies, our allies, [and] that the president is willing to keep a campaign promise. The president is not going to flinch from the threats of rogue nations. I think doing that, moving the embassy, I think it resonated in Iran. I think it resonated in North Korea, and I think it resonated with our allies as well. I think their view is, well, we see how America is willing to stand with an ally, we also want to be an ally. We want to be an ally like Israel and get the same benefits and work within that same circle of trust and circle of peace. So, I think that, in addition to it being a personal achievement that I am very proud of, I think that it served the entire foreign policy efforts of the administration.

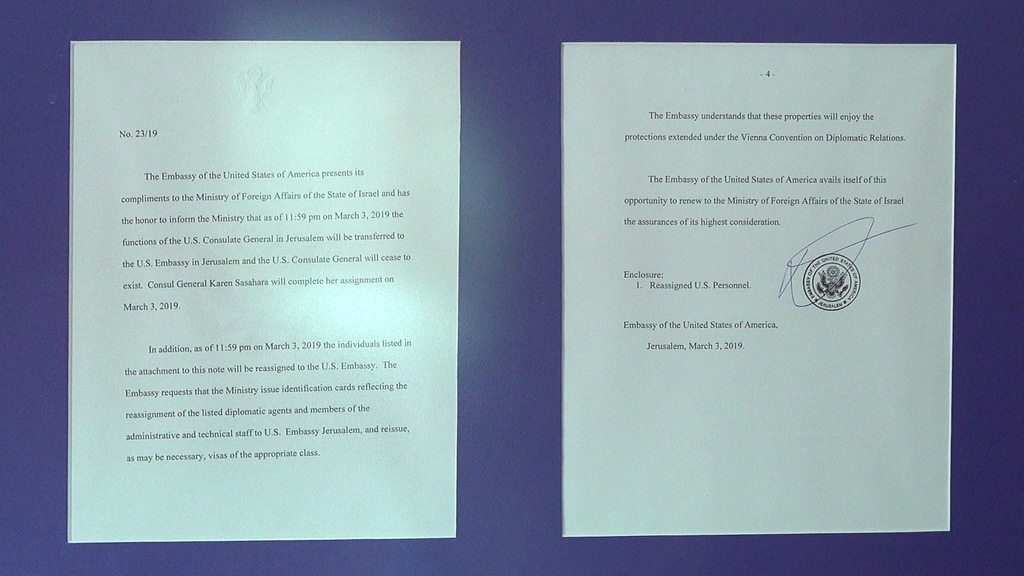

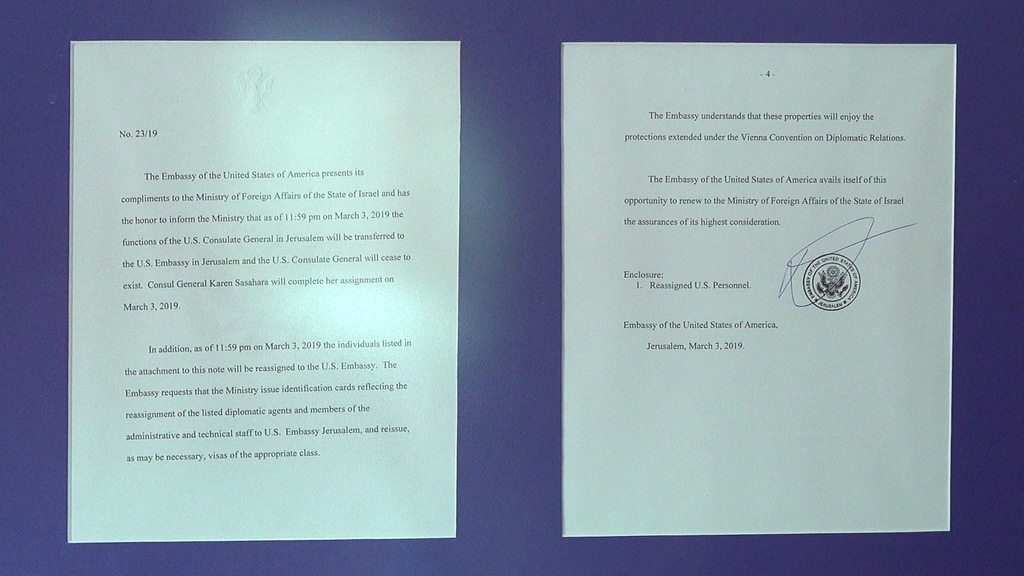

8 View gallery

Memo informing the Israeli Foreign Ministry that the U.S would close its consulate in Jerusalem and move its embassy to the capital

(Photo: Courtesy)

TML: It’s interesting how you shifted over the years and are now spending so much time in the Arab sector. It’s not just a business deal, is it?

Friedman: Oh no, not at all! Certainly not. To me, the value here is not in the commerce. There was lots of commerce before, and that doesn’t get me up in the morning to see people doing business with each other, although it’s obviously important. It’s about changing the hearts and minds of a generation of people so they come to see each other as human beings subject to respect, religious tolerance and human rights. I mean, it’s all about changing the way Jewish people and Arabs, and Arab-Israelis and the entire region begins to look at each other in a way where they can coexist. And more than coexist. It’s not just about tolerance. I remember one of the Arab leaders, and I won’t mention his name, said to me, “I don’t know why everybody is so hung up on tolerance. It’s a pretty low bar. You tolerate a headache. You tolerate a pain in your foot. Why can’t we elevate this to loving each other? Why do we have to just tolerate each other?”

It moved me greatly. It really did, and the relationships here are honest. They’re sincere, and I think everybody wanted to get to this place. It was difficult to do so, but I think one of the leaders of the UAE said: “Look, we needed the help of the United States to help us get there. We didn’t know how to close the deal.” And now that we have, I think that everybody just feels really good about it.

TML: You have a documentary and a book coming out simultaneously. I think it was in one year that you put this together.

Friedman: I wrote the book in January and February of 2021. It’s coming out February 8, 2022, so it’s about a year from putting pen to paper to being released. The documentary started the same time. It’s going to come out a little earlier. We’re going to screen a 38-minute condensed version at the launch of The Friedman Center on Monday night. I’m very proud of both. I hope they are well received. I really enjoyed writing it, and producing it, and narrating it, and scripting it. All of these things are new to me.

TML: Are they similar?

Friedman: No, they’re not really. I mean, the book is a memoir. The book is my story of sort of going from outside of the political world coming in, what I found, how I navigated through it.

How I worked with the leaders of the United States and the rest of the world to try and get from Day One until the Abraham Accords. The movie is really told through the voices of all of the participants, so we went around the world and we had long conversations with the president and the vice president and the secretary of state. With Jared Kushner and with Avi Berkowitz, with the foreign minister of Bahrain, and the prime minister of Israel, with Ron Dermer, with Benny Gantz, with Gabi Ashkenazi, [and] with many of the leaders of the Arab world, with [UAE Ambassador to the United States] Yousef Al Otaiba. We had all of these long conversations, and we let them tell the story. It’s their story. Not my story.

TML: What are the titles?

Friedman: Well, I think the movie is called The Abraham Accords. The book has a little bit more of a colorful title. It’s called Sledgehammer: How Breaking with the Past Brought Peace to the Middle East. And that’s kind of my sort of having to cut through the inertia, the ice, the reticence of the foreign policy apparatus in America to get to the point I got to.

8 View gallery

Amb. David Friedman and his wife, Tammy, center, visit the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi

(Photo: Screenshot from the documentary The Abraham Accords)

TML: Your father was a prominent rabbi. What would he be thinking today?

Friedman: Well, if there is a question that could bring me to tears, you’ve asked the right question. It’s the greatest disappointment of my life that my father didn’t live to see this, because he loved this whole world. He was a wonderful man, committed to the Jewish people, committed to the State of Israel, extraordinarily successful, very good at what he did, tall – much taller than me, dignified looking, white hair, kind of looked like Moses or what people thought Moses looked like. In the latter years of his life, when I was a lawyer, we spent a lot of time together. We talked about my activism for Israel, but it was nothing compared to being an ambassador. He didn’t live long enough to see my nomination or my service, and my mother was too ill as well to really appreciate what was going on.

So, as someone who grew up real close to their parents, and craved their approval, engaging something which undoubtedly would have garnered that approval and not having them there to share it was deeply disappointing. If he were alive today, he’d be, I think, over the moon with happiness and pride.

TML: In our conversations, you mentioned deconflicting Jerusalem. Can you describe what deconflicting Jerusalem means?

Friedman: Yeah, sure! I mean, Jerusalem needs to be one city in peace. It needs to live up to its name, right? It means City of Peace. That means, externally, helping to, as I said earlier, helping to bring thought leaders and people who have never been to Jerusalem, who have misconceptions about it, who can come and see, as I’ve said, Jerusalem, how Israel and all of the authorities in Jerusalem respect the religions of all major faiths.

Inside the city, and I think this is something I’ve had many conversations with both Mayor Barkat and Mayor Leon, and they’re continuing, and I’m very happy with what they’ve done, to get to a point where every resident in Jerusalem, just like every other resident in Jerusalem, if you want to have an undivided city, and the United States has recognized Jerusalem as an undivided city, of course the State of Israel recognizes Jerusalem as an undivided city, and I certainly do, you must get to the point where it’s truly undivided. Not just geographically, but also in terms of the residents how they see themselves, how they participate in the city.

I’ll give you an example. Toward the latter part of my time as ambassador, I saw a couple of new schools that were built in the Arab sector of Jerusalem. I got a tour of them. I met with some of the parents. They used the Israeli curriculum, not the Palestinian curriculum. The students there are thriving and the parents there came to me and said that this is a game-changer. Our kids are going to be doctors, and engineers, and lawyers, and scientists just like the ones that go to the Israeli schools.

That process, it’s not over yet, it’s not complete, but I do believe it is the goal of the Israeli leadership, and it should be accelerated. Because that, to me, is the sure-fire way internally of making Jerusalem a place that is not a city of conflict. That’s something that I don’t really have much influence on. I’m more focused on the external perception of Jerusalem, but I think both have to go hand-in-hand.

TML: Your role as ambassador brought your family into the political realm. Your wife Tammy has been involved in many of the things that you’ve done, and I’m sure some of the other family members. How have you seen the growth through the lens of your own family?

Friedman: Well, I don’t think I could have done this if I didn’t have the support of my family. There is nothing more important to Tammy and I than our kids’ welfare, their safety, their security and their happiness, and so I didn’t really know when I started whether this would be something they would embrace, or whether this would be something they would run from, because you don’t know. Fortunately, my kids were old enough and mature enough to understand what the job entailed. To understand the level of tension that would be brought upon us as a family. I think they loved it. I think they’re all proud of us. They are proud of Tammy and me. We’ve done everything we can to include them in as many events and to have them participate. Again, they’re all old enough to appreciate what’s going on. I think it’s been a great ride for all of us, so I think we’ve come out of this on the other side, thank God, intact, and we’ll look for the next adventure.

TML: Thank you, Ambassador Friedman, for your time in your lovely home, and I wish you good luck!

Friedman: Thanks, Felice! I appreciate it.