Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

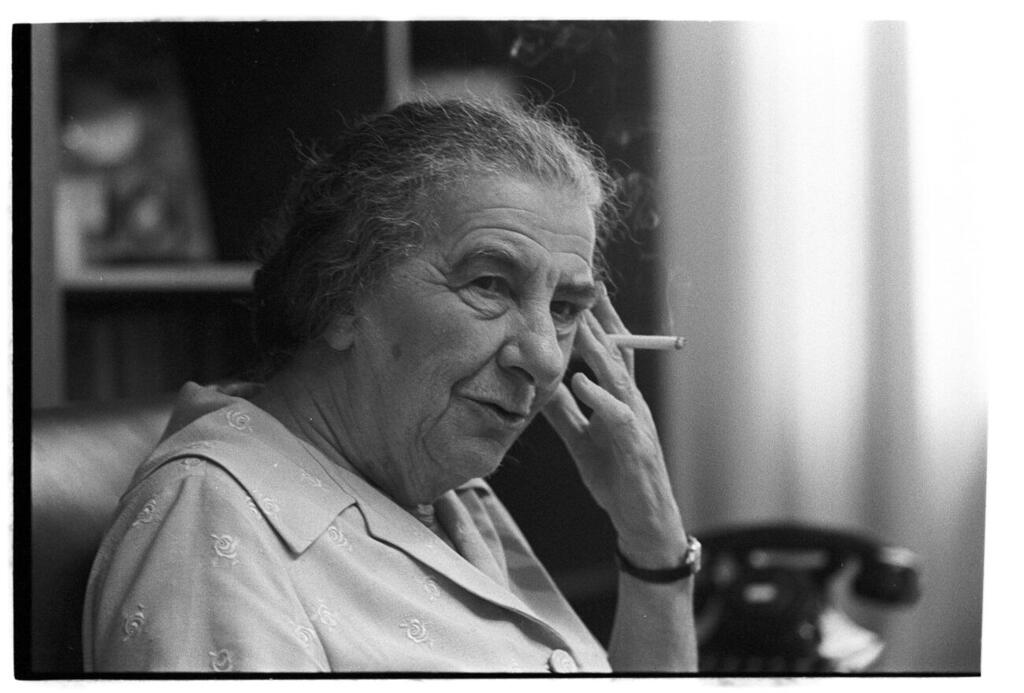

On the evening of September 25, 1973, Golda Meir arrived at a Mossad facility not far from Tel Aviv. Israel's prime minister, then 75 years old and recovering from another bout of cancer, the first woman in the position, and a towering figure in Israeli politics and public life for five decades, entered a small conference room, one of its walls made of one-way glass. Facing her on the chair sat Hussein bin Talal, the king of Jordan.

More stories:

This was not the first time the two had met. After the devastating defeat Jordan suffered in the Six-Day War, King Hussein changed his strategic approach and was willing to do anything to avoid another war with Israel, including maintaining secret contacts with its leadership.

"Hussein was in a precarious position," explains Moshe Shwardi, an intelligence and security researcher who has extensively studied the Yom Kippur War. "He found himself between a hammer and an anvil, or rather between a hammer and Sadat, the president of Egypt, who wanted to regain the territories occupied in the Six-Day War. To his north was Syria, which wanted the Jordanian army for its own defense and suppression. But Hussein wanted to preserve his kingdom. Therefore, he was willing to cooperate with Israel."

Since becoming prime minister in 1969, Golda had at least 12 personal meetings with Hussein, sometimes near Eilat and sometimes near Tel Aviv. The Jordanian king spoke fluent English to Israel's leader, who grew up in the United States, and both experienced statesmen established a friendly relationship.

The meetings between Golda and Hussein, held under a heavy cloak of secrecy, were supervised by the Shin Bet, which gave the series of meetings the codename "Operation Puppet." Reuven Hazak, then head of the operational unit in the Shin Bet and later deputy director of the agency, was responsible for the operation on behalf of the Shin Bet.

"Golda's meetings with Hussein always started with casual conversations, with Golda telling him about the tomatoes in Kibbutz Revivim (where her daughter, Sarah, lived)," testified Hazak as part of an upcoming research. "In meetings near Eilat and other meetings, we saw that she was not in good health. It was difficult for her to move, and we could see her struggling."

Despite her health condition, Golda stood firm for the meeting with Hussein, sharp as a knife. She knew from experience that the Jordanian king often arrived at their talks armed with highly classified intelligence. She was right.

On the evening of September 25, just a day before the eve of Rosh Hashanah in 1973, the meeting began with pleasant small talk. About an hour later, Hussein broached the central topic that had been troubling him on his way to Tel Aviv. He shared his concerns with Golda following a meeting he had two weeks earlier in Cairo with Sadat, the president of Syria, Hafez al-Assad, during which they discussed the possibility of war breaking out if there were no diplomatic moves toward Israel. A few days later, Hussein met with King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, who conveyed similar information.

And that wasn't all. Hussein provided Golda with sensitive intelligence from a highly reliable source in Syria, indicating that something dramatic was about to happen. "We learned from a very, very sensitive source in Syria... that all their units that were supposed to be in training and prepared to engage in Syrian action (against Israel) are now, in the past two days, in a pre-attack position," revealed the king.

"This includes their aircraft, missiles, and everything else, stationed outside, at the front lines, at this stage. Right now, it's all disguised as exercises, but based on the information we had in the past, these are pre-jump positions, and all units are in these positions. Whether it has any specific significance or not, no one knows, but I have my doubts. Nevertheless, no one can be sure. We must treat such matters as facts."

Golda had to take the implications seriously. "Is it possible that the Syrians will initiate something without the Egyptians' involvement?" she asked Hussein, who replied, "I don't think so. I believe they will cooperate."

This moment was etched in the memory of Reuven Hazak, who sat on the other side of the one-way mirror at the time. According to his account, it seemed that one intelligence officer, who also sat on the other side, was taken aback by Hussein's words. "I remember him jumping from his seat and saying, 'War!'," Hazak testified to Shwardi.

Zizi Kanizar of the IDF Intelligence Directorate and Golda reached the same conclusion. "When the meeting ended, and Hussein left, I entered the room where Golda was sitting, and Lev Kadar (her personal assistant and confidante) joined her," Hazak recounted in his testimony. "Then I remember Golda saying to her, 'This will be bad.'"

"The question Golda asked – whether Syria would go to war without Egypt – was the most professional question to ask Hussein at that moment," Shwardi said. "Although Golda claimed over the years that she was not a general, she had good instincts. She was the one who solved the puzzle, just like Intelligence officer Kanizar, who jumped and said, 'War.' Hazak's testimony about Golda's words at the end of the meeting also gives an indication of what Golda really thought fundamentally before the intelligence assessment analyzed her meeting with the king and corroborated Hussein's warning."

Intelligence experts indeed downplayed King Hussein's warning. At the end of the meeting, the shaken Golda updated her defense minister, Moshe Dayan, who verified the information with AMAN (Israel's Military Intelligence) and the chief of staff.

However, after military consultations, intelligence officials estimated that Syria's offensive capabilities were intended, in the worst-case scenario, for a limited operation as retaliation for an incident two weeks earlier when Israeli Air Force downed 12 Syrian MiGs.

Hussein's critical connection between Syrian preparations and Egyptian cooperation was completely omitted from the intelligence discussions. Kanizar's desperate attempt to influence AMAN's commanders failed. The widely circulated conspiracy theory was never substantiated.

Hussein's warning was dismissed to the point where Golda felt comfortable flying to Strasbourg the next day for the Socialist Parties' conference. Later, she even decided to extend her stay by one more day to meet with Austrian Chancellor Bruno Kreisky. Only upon her return to Israel on October 3rd did the prime minister hold a situation assessment, which ultimately led AMAN to adopt a low probability of war, burying Hussein's warning.

Three days later, the Yom Kippur War broke out. "An intelligence warning, from the moment it is received from the source until it reaches the end-users, is like an ice cube under the sun," summarized Shwardi. "Many ice cubes melted between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur of 1973."

However, not only Hussein's warning was dismissed by Israeli intelligence experts. Golda Meir's character and legacy were also tarnished due to the colossal failure of Israeli intelligence in the autumn of 1973. After the dust of war settled, the narrative was established, blaming Golda as the primary responsible party for the Yom Kippur fiasco, partly because as prime minister, she repeatedly refused Sadat's "outstretched hand for peace."

Meir was also accused of mismanaging the war, with allegations that she lost her composure during the hostilities. Consequently, Golda became repeatedly labeled, among others by some interviewees in this article, as the "worst prime minister in the history of Israel."

There is a significant degree of justification in the criticisms directed toward Golda, as she held the utmost responsibility for Israel's security as the head of government. Golda herself contributed to shaping her image when she resigned from the premiership after the Agranat Commission, which investigated the war's failures, absolved her of all blame. By doing so, Golda indirectly assumed responsibility for the Yom Kippur fiasco.

Even the historic peace agreement with Egypt, built on the battlefield of that war and remains a significant strategic asset today, did not alter Golda's public perception. The prevailing narrative remained intact.

However, now, on the 50th anniversary of the Yom Kippur War, with the recent publication of previously classified documents and new testimonies, other voices are emerging. These voices do not exonerate or "acquit" Meir of her responsibilities, but they do emphasize points in her favor. It is now evident that Golda not only had the ability to obtain high-quality intelligence from sources such as King Hussein, ask pertinent questions, and draw accurate conclusions, but she was also the one who most clearly opposed AMAN's misguided perception, which insisted that war was not imminent.

Perhaps this is also the reason why Golda Meir has recently experienced a kind of renaissance: a new Hollywood movie featuring Helen Mirren as her, directed by Israeli Guy Nativ, will hit theaters worldwide this summer. A documentary about her life, directed by Yariv Mozer, will soon air on Israeli television.

Historians and researchers also understand, over the years, that she was a complex figure - not angelically holy, but certainly not the demon that was firmly established in the Israeli consciousness. A multifaceted woman, much like life itself.

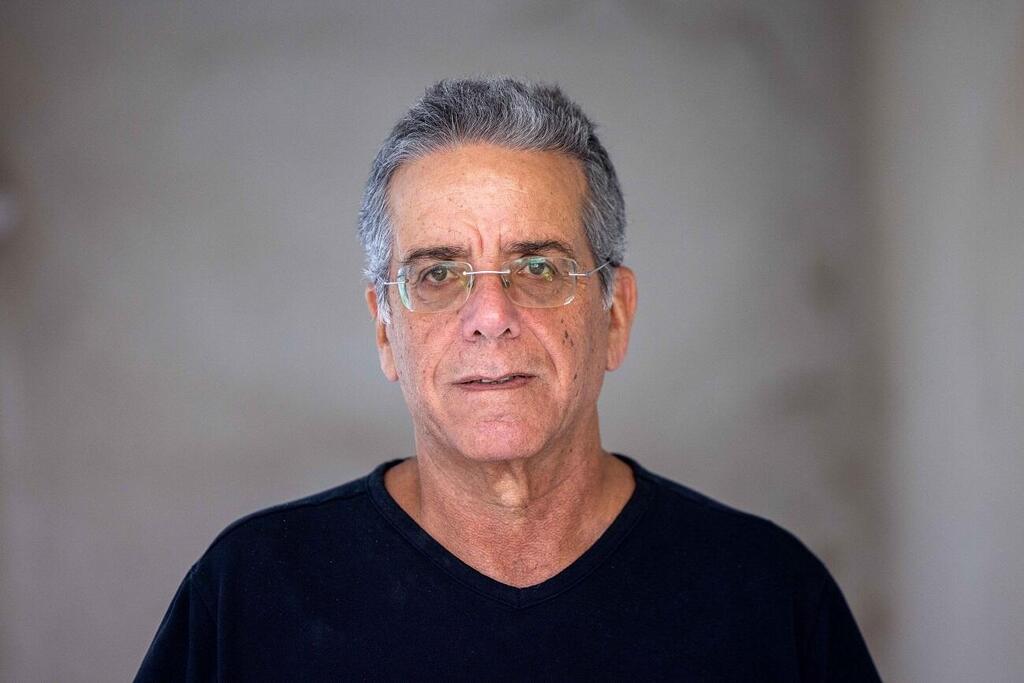

Shaul Rachavi, 66, one of the few people in the country who had real-time knowledge of Golda-Hussein meetings, is one who watches this renaissance of Golda with excitement. "We understood that such conversations took place, and there was excellent chemistry between them," Rachavi smiles. "We understood it from what grandma told us."

Rachavi is one of Golda's grandchildren and heads the Golda Meir Institute for Leadership and Society for her commemoration. "I have always been certain of her righteousness, but I am also biased," he says in a rare interview.

"However, in recent years, more and more official documents are being published that prove she was right. Later, she said she would never forgive herself for not listening to her heart whispers, but she faced people with rich security backgrounds, such as Chief of Staff during the Six-Day War Moshe Dayan, former Chief of Staff Haim Bar-Lev, and IDF Commander Yigal Allon (all serving in Golda's government shortly before and during the war), who reassured her that the IDF was well-prepared to repel any attack."

According to Rachavi, those who propagated the smear narrative against Golda were "hatemongering politicians from the left. They didn't like her because she was a political hawk, while they were doves, and it served their political agenda. They are not willing to acknowledge the fact that until 1974, Arab states refused any direct negotiations with Israel without prior conditions. The biggest injustice toward her came from parts of the Labor Party, and later from Meretz. It was a terrible injustice with elements of misogyny and character assassination. They treated her with disdain for many years."

The current focus on Golda's character, Rachavi argues, "is a correction of that injustice. From a distance of years and a bird's-eye view, it is possible to reexamine the war in a different light. The true heroes of the war are primarily the fallen soldiers, the wounded, those who fought, and those who led the military victory – and it was a military victory. But this victory was achieved in large part due to my grandmother's determination and the way she led the war cabinet and the strategic goals she set from the beginning, which were ultimately achieved through direct negotiations with Egypt."

Rachavi is admittedly biased, but his view gains support from the book "The Day Will Come and the Archives Will Open," published last year (Carmel Publications). Based on comprehensive research, relying on thousands of documents, many of which were previously classified, the authors, Dr. Hagai Tsoref and Dr. Meir Boimfeld, depict Golda Meir's tenure before and during the war and draw fascinating conclusions.

"I am a Yom Kippur War veteran, and like many war veterans, I had grievances about the leadership," says Tsoref, who worked in the national archive for years, where he came across numerous materials regarding Golda. "What I discovered based on thousands of documents revealed by the national archive for research purposes is that the commonly accepted perception of Golda being solely responsible for the war is not complete, balanced, or fair."

Tsoref and Boimfeld chose to title their book "The Day Will Come and the Archives Will Open," quoting their research heroine. According to Tsoref, "In early December 1973, when she was accused by the Labor Party leadership of contributing to the outbreak of war, she said, 'The day will come, and the archives will open, and everything can be published. There will be very important and interesting things that will surely prove that our path was for peace and that we did not prevent peace.'" And indeed, the documents discovered by Tsoref and Boimfeld tell a new story, not only about Golda but also about Sadat and his extended hand for peace.

The prevailing perception that has taken root is that Sadat attempted several peace initiatives before the war – including through the U.S. Secretary of State Kissinger and UN envoy Jarring – but Golda, arrogantly and stubbornly, rejected these moves. It appeared as though the Egyptian president had no choice but to resort to war.

However, it now turns out that in the years leading up to the war, Golda sent several envoys to Sadat and offered him to engage in secret peace negotiations, anywhere and at any level he chose. The Egyptian president rejected all these proposals, at least 15 in number.

"This proves that contrary to the allegations, Golda did not seek to preserve the status quo but was genuinely seeking order," says Tsoref. "It was not a stubbornly belligerent government; rather, it had a tough and cautious policy that offered an alternative diplomatic approach primarily safeguarding Israel's vital and existential interests during those years."

Why, in your opinion, is this narrative not ingrained in the Israeli consciousness?

"Golda is somewhat to blame for her own image. She was very discreet, never revealing anything, not in her memoirs or in interviews. She never spoke at all about the envoys she sent to Sadat. State documents remained classified for decades, and until they were declassified, these things were not revealed.

Additionally, the Yom Kippur War was a severe trauma for Israeli society, and they sought someone to blame. Golda became the scapegoat. Even today, when I present the research we conducted about her, people are unwilling to accept it. The older generation, no matter what you tell them, they are convinced that Golda is to blame, and anyone who claims otherwise is a revisionist historian."

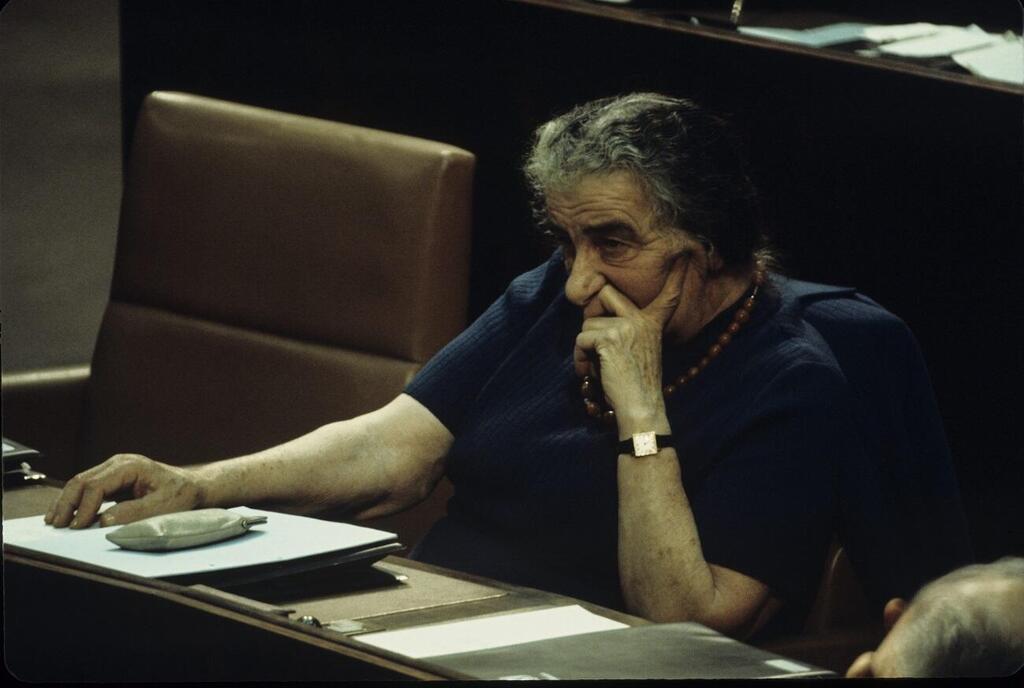

Even documents from the war's management, including a diary written by Golda's office manager Eli Mizrachi, serve Tsoref and Boimfeld to paint Golda in different colors than usual. "Golda was a determined force in the war," Tsoref asserts.

"She led the war, in its political aspects, with wisdom and determination, while relying on her senior ministers Dayan, Alon, and Galili, as well as former Chief of Staff David Elazar and Mossad head Zvi Zamir. What we learn from the documents is that Golda set clear objectives in the initial stage of the war, objectives that seemed entirely unrealistic given the situation in the first few days. But she managed the war while looking at the day after and wanted to achieve a position of strength in negotiations."

For instance, after the battles in the Golan Heights, Golda approves the IDF's crossing of the ceasefire line with Syria to occupy additional territory. On the southern front, she also insists on the success of the airlift to the Egyptian side.

During a government meeting held on October 21, while negotiations for the war's cessation were at their peak, one of her ministers confronts her, claiming that the territorial gains in Syria and Egypt involved significant losses. She calmly responds, "It is impossible and forbidden to calculate which action caused more losses. When shooting, there are losses, and it is inevitable to be otherwise. But in my opinion, these two decisions (to attack beyond the ceasefire lines in Syria and Egypt) saved losses and put us in a position that at least equals the Arabs (in terms of diplomacy)."

According to Tsoref, "These are precisely the type of decisive decisions a prime minister needs to make during an existential war."

Golda Meir, born Golda Mabovitch in 1898 in Kyiv to a Jewish family, immigrated to the United States at the age of eight, where she grew up and received her education. At the age of 11, she led a protest because some of her classmates couldn't afford to buy textbooks.

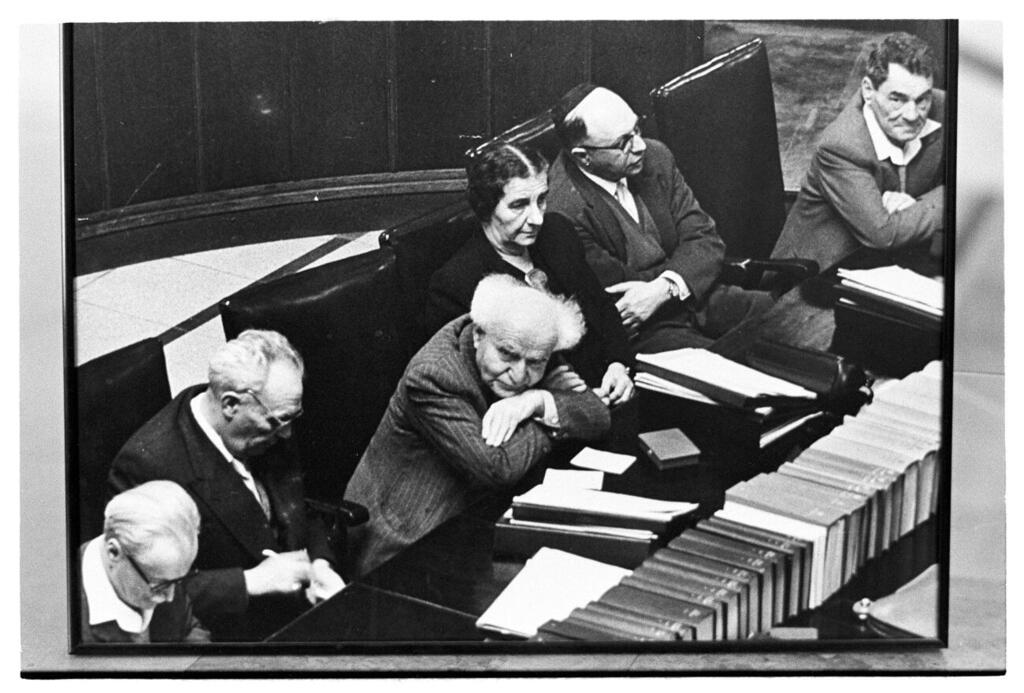

In 1922, shortly after her immigration to Eretz Israel, she was elected as the secretary of the Poale Zion Council. From there, she advanced in the political system and acquired more and more skills as a stateswoman. During the Independence War, she was sent by Ben-Gurion to the United States to raise funds for the war effort, and she succeeded in this mission beyond expectations. Afterward, she was appointed by Ben-Gurion to serve in the Labor Party.

Despite being the highest-ranking woman in Israeli politics during her early years, Golda discouraged women from competing for positions of power and opposed discriminatory laws against women. "The fact that she was a woman does not mean she was a feminist," says historian Avi Shilon. "She was a very cunning politician."

In 1956, she was appointed to the coveted position of foreign minister, a role she held for a decade. In 1966, after being diagnosed with lymphatic cancer, which she concealed from the public, she decided to retire. The disease was kept at bay, but it had an impact on her, causing pain and requiring her to take medication.

"After retirement, she thought she would take care of herself at home, but as soon as they convinced her to become Mapai secretary," her grandson Shaul Rachavi recounts. "She took up the task."

Golda also accepted the position of Mapai secretary after the death of Levi Eshkol during his tenure as prime minister in order to prevent an ugly succession war between the two main contenders for the throne – Yigal Allon and Moshe Dayan. The Labor Party decided to appoint her to the position. It is widely believed that Golda became prime minister unexpectedly, but after taking office and winning the 1969 elections, she shattered records of public support and admiration.

The contrast between Golda's image as a grandmother figure and her conduct as a prime minister was filled with a certain degree of determination bordering on cruelty. In the leader’s biography by Meron Medzini, she is described as "a political animal without restraints and with an iron will... Sometimes, tendencies toward ruthlessness were revealed in her. She could be embarrassing, annoying, stormy, passionate, and stubborn... She embodied the best qualities of the Jewish people, but at times, she also highlighted some of its worst traits."

From a political perspective, as prime minister, Golda found herself mainly contending with Sadat, who was determined to regain the territories and honor lost by his country in the Six-Day War. Golda chose to approach Sadat with suspicion, aligning herself ideologically with the more right-wing faction within the Labor Party. For example, she supported the "Galili document," which set the Labor Party's policy toward the occupied territories of 1967 and effectively whitewashed the settlement enterprise in them.

The dovish camp within the party never forgave her for this. "Golda was a rigid woman, with a limited vocabulary in Hebrew, responsible for tearing apart the Labor movement and the Eastern Jews, which we still suffer from today," says Boaz Applebaum, who was then chairman of the Labor Party's student organization and one of the staunchest opponents of the Galili document. "She was emotionless, egoistic, and said about the Arabs that she would never forgive them for forcing us to kill them. What arrogance! She was intimidating. Even her ministers were afraid of her."

Against the backdrop of this political and diplomatic context, the critical days of autumn 1973 unfolded. Outwardly, Golda displayed toughness not only toward Sadat but also toward her ministers and anyone who threatened her political standing. Behind closed doors, as it turns out, she sent envoys to the Egyptian president and attempted to reach understandings that would allow for the start of diplomatic negotiations. "Publicly, she appeared quite resolute and held firm positions, but in closed rooms, she was very pragmatic," says her grandson, Shaul Rachavi.

Naturally, there were also reports indicating an imminent and approaching war. "It's true that there was hubris in Israel at the time, but my grandmother was more anxious than euphoric," claims Rachavi. "She was anxious about the outbreak of war, and ironically, that was what they criticized her for. They said she was making a mountain out of a molehill."

Then came the morning of October 6. At around 4 o'clock in the morning, the prime minister's telephone rang. On the line was her military secretary, Israel Lior, who woke her up following the report from Mossad chief Zvi Zamir about his meeting with "The Angel," Ashraf Marwan, a senior Egyptian spy Israel had at the top echelon of the Egyptian leadership. The message was that war was about to break out at 6pm "Today, war will break out," he said. She replied, "I knew it would."

Golda got up, dressed, and headed to her office in the IDF headquarters, not far from her home in Ramat Aviv. She asked to immediately summon Dayan, Alon, Galili, and the chief of staff, who would form her war cabinet in the coming days.

Even this time, under genuine existential pressure and anxiety, the protocols reveal how Golda managed the situation skillfully and calmly. "In the morning discussions on the war, Dayan said things like, 'Based on Zvika's (Zamir's) information, we don't mobilize all the reserves,'" says Or Pialkov, a historian of the Middle East, terrorism and Israeli wars, and an active member of the "Center for Yom Kippur War Studies."

Head of Military Intelligence, Eli Zeira, shares a similar view and tries every morning to persuade decision-makers that war won't break out. On the other hand, the prime minister took the war seriously, and regarding the reserve mobilization, she said, “If there really is a war, we need to be in the best position possible."

According to Peliakov, "even later on, unlike Dayan, who became uncertain and spoke in terms of the destruction of the state, Golda entered the spirit of battle and made truly important decisions during the war."

Peliakov refers to an interview that Yigal Allon granted to Raudor Menor of the Davis Institute for International Relations at the Hebrew University before his death. The interview, given in 1979, was archived and published only 20 years later, providing a glimpse into Golda's psyche during those turbulent days.

"Golda was tormented by how we were caught off guard, and to her credit, it can be said that she did not try to evade her responsibility as prime minister," says Allon. "But she got used to thinking that she was surrounded by people who knew their job, that security was their profession. AMAN had international prestige, and we were almost prisoners of our own myth. An excellent chief of staff, a defense minister with a global reputation, and she took comfort in the fact that, after all, she decided in favor of a large-scale reserve mobilization and regretted not making that decision a day earlier."

Throughout October 6, the top echelons of the government failed to comprehend the scope of Egypt and Syria's military achievements. Only on the following afternoon, after Dayan returned from a tour of the southern front with a pale face, he and Golda recognized that Israel was on the verge of a catastrophe.

"I was present in Hadera when Dayan came to her with a gloomy expression," Allon recounted in the interview. "But she didn't break down... I didn't find a single situation where she collapsed. That is, in the sense that she stopped making decisions."

One person who understood well the dynamics between the prime ministers and the intelligence chiefs is Maj. Gen. (Res.) Amos Yadlin, former head of AMAN. "When the top military echelon presents a certain understanding to Golda, and she is supported by a defense minister who was also the chief of staff and an outgoing chief of staff, and in her government, there was also a chief of staff at heart, and others, and they all give her this assessment, she accepts it. She has no means to challenge it," said Yadlin this week.

"Since the Yom Kippur War, the prime minister challenges the military echelon, asks them many questions, tries to get additional assessments, etc. Prime ministers also insist on reading raw intelligence material and listen to other sources within the intelligence system, but that's all in hindsight. In the situation that existed then, it was almost impossible for Golda to act differently."

But not everyone accepts this narrative. Yossi Beilin, who was the Labor Party spokesperson in the years following the Yom Kippur War, argued that "Golda Meir was an Israeli patriot, but she was also the worst prime minister Israel ever had. She was not suited for the role, and she should not have been appointed to it. She could have prevented the Yom Kippur War, and she didn't prevent it. When she stood at the crossroads where she had decision-making power, she caused immense damage."

Beilin recalls a meeting that took place in 1978 at the Labor Party's advisory committee, of which Golda was a member even after stepping down from the premiership. "During that meeting, they talked about Begin and Sadat receiving the Nobel Peace Prize due to the Camp David Accords," Beilin recalls.

"Then Golda says, 'Maybe they deserve an Oscar, not a Nobel Prize.' It was one of the most foolish things she could say. Madame, you are responsible for the war breaking out, show some modesty. There's an Israeli-Egyptian peace for heaven's sake, the existential threat over Israel was removed. And you say they should get an Oscar? I heard this statement and was simply appalled."

According to her grandson, Rachavi, this remark by his grandmother was a satire at the expense of the pompous theatrical personalities of both leaders and reflected her sarcastic sense of humor. Perhaps it was another reason why she sometimes found it challenging to explain herself, thereby impacting her legacy.

"You have to be as naive as Yossi Beilin not to understand this joke," Rachavi says. "Already in the post-war days, I saw how the negative sentiment against her was building up," he continues. "I remember having arguments with my classmates about whether she should resign before the elections or not. I, of course, argued that she shouldn't."

And how did she cope with the years after the war?

"In her final years, she added more to her work, traveled abroad, and held diplomatic meetings on behalf of the government of Israel. She visited Kibbutz Revivim, where we lived. People saw her as a tired and sick woman who genuinely felt wronged, even by her friends, who suddenly turned on her. You could see the burden she carried, the load."

Golda Meir passed away on December 8, 1978. Two days later, Begin and Sadat received the Nobel Peace Prize.