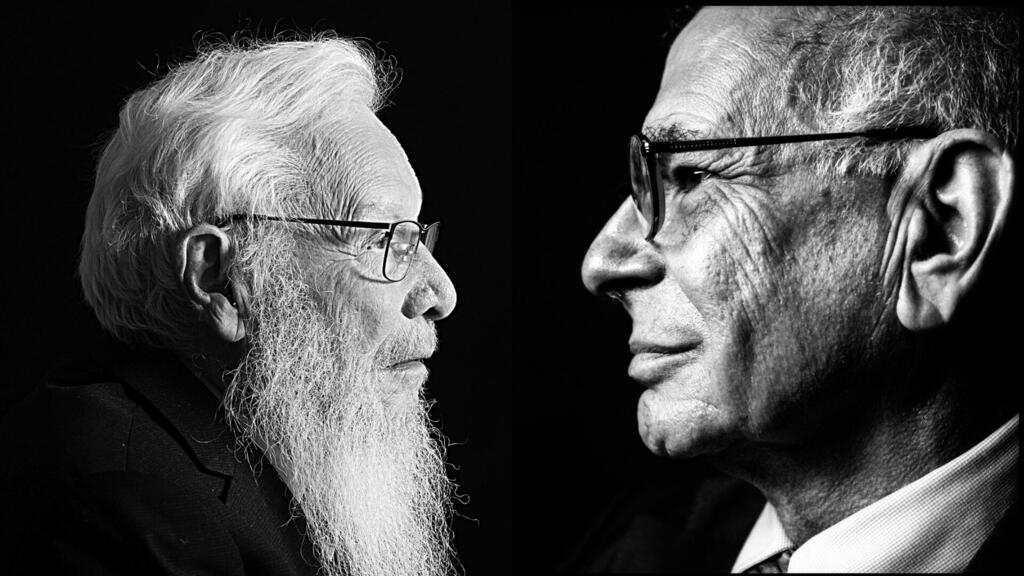

They compliment each other, but the only subject that Nobel laureates in economics Professors Yisrael (Robert J.) Aumann and Daniel Kahneman agree on is that there is nothing they agree on.

Other stories:

To me, they are like a modern version of Hillel and Shammai, the two great sages who debated almost everything almost 2,000 years ago. While the disputes between Hillel and Shammai were for the sake of heaven, the arguments between Aumann and Kahneman can get heated. Let's hope this time the story will end differently.

8 View gallery

Professors Yisrael (Robert J.) Aumann and Daniel Kahneman

(Photo: GettyImages, Alex Kolomoisky)

The disagreement between Kahneman and Aumann starts with a disagreement on the nature of human beings and expands from there. Prof. Kahneman received the Nobel Prize in 2002 when he showed (with the late Prof. Amos Tversky) that we are not rational creatures, and Prof. Aumann received the prize three years later when he showed (with the late Prof. Thomas Schelling) that we are actually much more rational than claimed.

Kahneman is a psychologist, Aumann a mathematician. Kahneman is an atheist, Aumann is a religious person. Kahneman lives in New Jersey, Aumann in Jerusalem. Kahneman is on the left, Aumann is on the right. They both express their opinions strongly, and both agree that this is a "struggle for the soul of the people".

The only identical answer I received from them was on the question: Are you optimistic about the future of the country? They both said no.

Kahneman is 89 years old and Aumann is 92, which means they have seen a thing or two, or 50. Both experienced the rise of Nazism in Europe; Aumann's family fled from Germany to the United States just three months before Kristallnacht, while Kahneman grew up in Paris under Nazi occupation. Kahneman made Aliyah to Israel in 1946, and Aumann a decade later. Both studied and taught at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Prof. Aumann still goes to his office on the Givat Ram campus almost every day, while Prof. Kahneman sits at Princeton University. Both have experienced fear, migration, and loss alongside tremendous achievements.

Although each of them learned a different lesson from history, the story of the two and their life paths is a source of pride and honor for every Jewish and Israeli person. When I tell them this and express my excitement at meeting Nobel laureates, it's like meeting the cream of the crop of human intellect and heart; only 989 people in the world have received the Nobel Prize to date (13 of them Israelis), and this is much more significant to me than any other meeting, certainly more important than the opinion of a random model or singer on the situation - they dismiss it with humor and ask not to make a big deal.

Despite their age and hearing aids, they are sharp and full of joie de vivre. If there is one thing that connects them, it is the thought of what their grandchildren will say about the article and the concern not to embarrass them. It's wonderful to me.

The two knew, of course, that I would interview them face to face, but they preferred to be interviewed separately. In general, Kahneman told me that he wouldn't advise any older person to put themselves in a position where they have to think quickly and have no control over the conversation. I talked to Kahneman via Zoom and met Aumann at his home in Jerusalem.

Prof. Aumann, can you understand the other side? The concern about Israel becoming undemocratic?

Aumann: "Look, any country can become undemocratic, right? But I don't understand the other side. They are disappointed with the [election] results, and I understand that. The left sees that a right-wing government was elected and they are not willing to accept the decision of the voter. I was driving on Begin Highway and there was a huge advertisement that said 'We need to resist dictatorship' in a threatening font, with a raised fist above it. It's scary. One of the slogans of the right that I sympathize with is 'They are stealing our elections'. Democracy is the rule of the people, you can't ignore that. My children don't think like me, they go to protests against the reform, but my grandchildren are more on my side now.

"If we are talking about a dictatorship, I strongly condemn the reserve soldiers who declared their refusal to serve. The army is not a business that you can come and go. Part of the thing about the army is to follow orders, it's not a voluntary association. If you volunteered, then you volunteered, from that moment on you are a soldier. It worries me very much, much more than the constitutional crisis. It's breaking the rules. You are talking about dictatorship? This is the direction toward a military dictatorship. It means: ‘I am the army and I can influence the decision-making through military action.’ No, no."

Kahneman actually sympathizes with the refusniks: "What has happened so far is legitimate, I think that's clear. There are people who volunteer and risk their lives for a country they believe in. Do you still believe in Israel? Part of the protest is actually saying that if this comes to pass, if Israel becomes like Turkey, it's no longer my country. Many people have this feeling and they will express it in different ways."

One of the arguments on the right is that the other side threatens to refuse service and immigrate whenever something that they don’t like happens.

Kahneman: "Right. Right. There is a limit. Until now, there was no agreement, but everyone lived with something they weren't satisfied with. It's not that the secularists were happy with supporting the Haredim, but they coped with the situation. This government tried to change the rules of the game and they cannot accept that. There were rules to the game. Now they have broken the rules. That's the story."

On the other hand, Aumann spares no punches for those who threaten to immigrate. "Those who leave are not Israelis," Aumann declares.

"I actually understand the other side," says Kahneman. "Although it's not one side, there are different sides to this issue: the ultra-Orthodox are very easy to understand. They have a different law and certainly don't want the law of the secular. A compromise must be made with the ultra-Orthodox. I think we need to reach a situation where they integrate into society in one way or another, especially economically if not in the military system.

I also understand the settlers. It's clear they are stopped by the Supreme Court. I also understand the racists, it's not complicated and we have enough experience with it. In my opinion, we also have no difficulty understanding the confusion regarding what democracy is. That is to say, if democracy is majority rule, then what do they want?

But democracy is not just majority rule, it is majority rule with safeguards that ensure, among other things, that the majority will not be perpetual. Once the majority also controls the judicial system, the temptation to use their power to perpetuate their rule is a temptation that no one can resist. So everything is understandable here."

It seems that the two have completely opposite perspectives on every issue. When we talk about checks and balances, for Kahneman, it’s simply tools that the judicial system has to control and stop the government - tools that the reform is trying to break up. Aumann, on the other hand, holds the opposite view. According to him, the reform is trying to restore them.

"I am very much in favor of a system of checks and balances," he says. "Today there are checks and balances on the Knesset, but there are no checks and balances on the judicial system. In the U.S., there are checks and balances in both directions, the judicial system on the legislative branch, and vice versa. Today we have a monarchy: there is no check on the judicial system, it does what it wants. We need checks and balances - in both directions. Reform is not a threat to democracy, on the contrary - the judiciary in its current form is a threat to democracy."

Is there a possibility of a compromise between the sides?

Aumann: "I'm not saying it’s all or nothing, certainly not. There are definitely things that can be discussed. The issue of the balance of powers, for example, I think there needs to be balance, but it should be within the judicial system. That is, not that the Knesset will overpower the annulment of a law by the Supreme Court, but that it will be more difficult for the Supreme Court to overpower the Knesset.

Now the situation is that a panel of three judges can annul a law with a majority of votes – that’s no way to go. I would say that it is funny if it wasn't sad. I suggest that the annulment of a law be done by a full panel of judges with a special majority. I would be in favor of 13, others say 12 or 11, there is something to talk about. But the principle of a special majority of the full panel must be preserved."

"On the other hand, I think that appointing judges is a key issue. There can be no compromise on this: I think it would be good if we had something similar to the U.S. Judges cannot appoint themselves. I am in favor of canceling the committee for appointing judges. The justice minister or the prime minister propose a list of judges, and then they go to a special committee or hearing, as in the U.S., and the person is examined. There must be a clear and strong reason to annul the appointment.

There is also the issue of attorneys general who are appointed by the Justice Ministry, not by the minister because he is a 'politician'. In general, the word 'politician' has become a derogatory term."

You can understand why.

Aumann: "But this is democracy. These are the people's representatives. I don't understand why it's derogatory; after all, we elected them. If we found them unworthy, we wouldn't have elected them."

Politicians think short-term, they have interests, coalition loyalty, and so on - isn't it better to rely on judges?

"No, no, no," says Aumann firmly. "This is actually the crux of the matter. Judges should judge according to the laws, whether you are breaking the law or not. They should not determine values and ideology, and interfere in issues such as settlements, illegal migrants or drugs - it's none of their business.

For example, [Finance Minister Bezalel] Smotrich suggested that we rely on FDA approval and the parallel body in Europe to approve drugs - and the attorney general forbade him from bringing it up for discussion. What's it to her? It's really out of place. Even if there is logic in her words, she has no right to interfere in the matter. Judges should judge according to the law - not say what is right and what is not, what is reasonable and what is not reasonable. Politicians are public servants, judges are bureaucrats. They are not elected, they are appointed. I prefer politicians who are elected by the public. I don't think everything is justiciable."

"I'm generally pessimistic about the progress of the reform," Aumann says. "I don't see anything happening and I'm not sure how [Prime Minister Benjamin] Netanyahu is responding to this, the Knesset returned from a break weeks ago and still nothing has happened."

They say this is a tactic.

Aumann: "Maybe we really need to take it slow. I would be happy if something happens."

Regarding a compromise, Prof. Kahneman doesn't sound like he's relying on it too much either. "Regarding whether there will be an independent judicial system that is capable of checking the government and that the government cannot control," says Kahneman. "This principle cannot be compromised. I don't think the protest will give in. There may be compromises on all sorts of smaller things on the sidelines, but the principle is too important to compromise on.

In the end, everything is in the details, right? If there are nine or 11 members in the committee, if there is an override clause with a regular majority or supermajority - but the question is whether a compromise is even necessary. There was an internal logic to the reform - to eliminate the Supreme Court as a floodgate. That's the principle. On that, there is no compromise, there can't be. Because once they take over the Supreme Court, the way back is very difficult.

You see it everywhere. It is very prominent today in the elections in Turkey. What was about to happen here was worse than in Turkey."

"It's clear that there are things to fix in the judicial system. But this reform is an overhaul. I think they know it on the other side, they're not hiding it."

Do you really think you can see Israel becoming a dictatorship?Kahneman: "Easily. It has stages and a fixed script, and we're already seeing glimpses of it. The script begins with taking control of the judicial system. The second stage is taking control of the media. Then it's organizations that interfere and annoy, and then it's individual rights. It's all heading in that direction. We have seen such attempts in relation to the media, individual rights, and organizations that are not favored by the government. It has already started. But there are still barriers, there are still those who will defend. It is clear that when these obstacles disappear, we will see the whole phenomenon.

It's not dictatorship in the classical sense: it's illiberal democracy. This process is taking Israel out of the free world, the Western world. It's happening and has happened in Turkey and Hungary, and is about to happen in India. Poland can currently allow itself various things because it helps Ukraine.

In other words, we see these processes. Netanyahu and [Justice Minister Yariv] Levin did not invent it. It's a process they are joining. Even the obstacles are, in a certain sense, just tactics. They are not sorry or regretful, they simply cannot achieve it at the moment. It's all tactics."

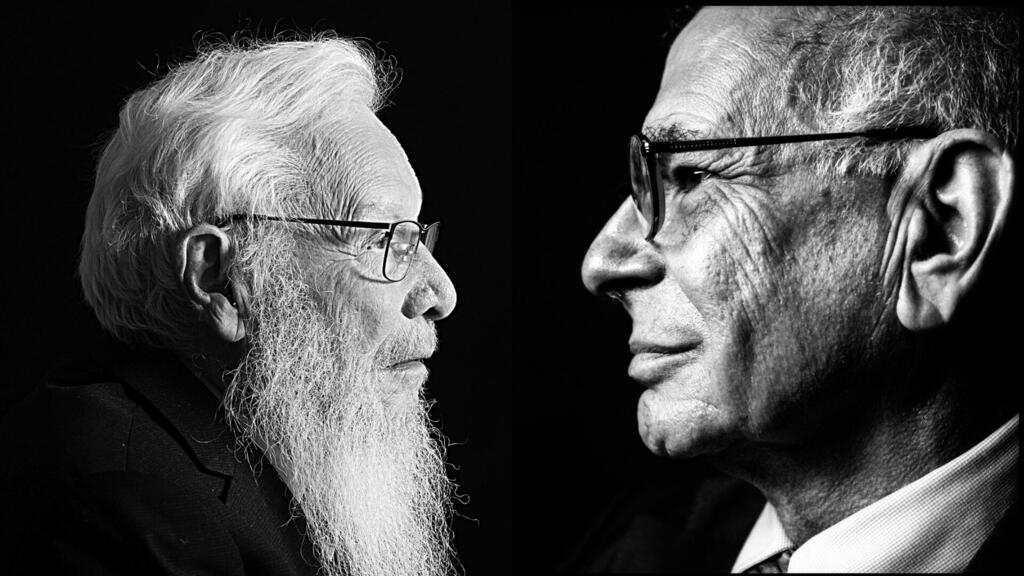

8 View gallery

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Justice Minister Yariv Levin

(Photo: Alex Kolomoisky)

Aumann: "One cannot say that Israel will not become a dictatorship; such a thing can happen to any country. But it will not happen because of this reform. On the contrary."

We are talking about the worst-case scenario, which is reaching a situation called a "constitutional crisis." What does it actually mean?

Kahneman: "Such a thing is a disaster if it happens. In a constitutional crisis, all the burden is placed on security forces, the army, and the Shin Bet. They will ultimately determine. Power will prevail. It is highly undesirable. It is also not a given at all that the entire army will stay united as a single unit. Someone will be forced to yield, or there will be a civil war. And that's a nightmare."

Aumann: "When can a constitutional crisis occur? If the government passes an override clause in its original form, with a majority of 61, and then passes a law that the Supreme Court nullifies, the Knesset overrides it, and the Supreme Court nullifies it again—then who will the army and the police listen to? I hope it doesn't come to that. I think there is consensus on the right that the majority needs to be larger."

There are already voices discussing national divorce and civil war. I think it is a moral travesty and also practically impossible. What are your thoughts?

Aumann: "Anything can happen. I really hope we don't reach that point. In any case, I will not participate in such a thing."

I'm glad to hear that. Neither will I. And what about the divorce between Israel and Judea?

Aumann: "It's good that people still remember the Bible. That was truly a tragedy. Anything can happen. But I don't think it will happen, and I don't see it on the horizon."

And we can find some agreement here too. "A civil war is a nightmare," says Kahneman. "It seems distant and impossible, partly because the external enemy is so close. A civil war is national suicide. So I don't believe it will come to that. But a constitutional crisis? One misstep is enough to cause it."

A misstep?

Kahneman: "I think the leaders of the overhaul did not imagine what is about to happen, so their foresight has been proven imperfect. They can make another mistake. They may think that if they simply ignore the Supreme Court or if there is a constitutional crisis, they will win. I don't trust them to have wisdom. Of course, there are different degrees of distrust, and I trust Netanyahu more than Levin or [Constitution, Law and Justice Committee Chair Simcha] Rothman or [National Security Minister Itamar] Ben-Gvir."

And national divorce? Such voices are rising. The State of Israel versus the State of Judea.

Kahneman: "That's a solution where both states are only for Jews," he laughs. "It's not possible. Among other reasons, because Judea is so dependent on Israel and cannot exist without it. The protesters represent a public that essentially supports the other side. They are not the majority, but they pay much more in taxes and fund what is happening. I don't see divorce happening."

Let's talk about the impact of the reform on the Israeli economy.

"The reform is a disaster not only in ethical terms," says Kahneman. "It will have tangible consequences on the economy. Heavy damage has already been done, and it will be difficult to repair. The future of investments in Israel is at risk. Investors perceive the political risk, and what the judicial overhaul has immediately caused is a significant increase in the political risk of investing in Israel. Capital is fleeing from Israel, it's already happening. You don't need to be an economist to see that."

"The danger," says Kahneman, "is that Israel will no longer be regarded as a democracy in the eyes of the world. The reform aligns Israel with countries like Hungary and Turkey that pretend to be democracies but are not. This is already being discussed today in the United States and Europe. There is no doubt that it will have an impact on investments. Even the high-tech sector will not remain in Israel."

As early as January, Kahneman signed a petition with hundreds of economists from Israel and around the world, opposing the government's steps to weaken the judiciary.

The letter warned against harming the Israeli economy and downgrading Israel's credit rating, as has happened in Poland and Hungary since Moody's downgraded their rating forecast, and other warnings are being realized.

Is the process reversible?

Kahneman: "It will take time. The damage that has been caused will last for years. What will Israel be like in a few years? If there was a constitution, there would be something to rely on, but I don't exactly see at the moment what can make Rothman and the politicians agree on a constitution."

Prof. Aumann, Moody's has downgraded Israel's rating forecast, economists from around the world are sounding the alarm, capital is leaving. Are they all wrong?

"The answer is yes. They are all wrong. Economics is a very sensitive matter. People invest when they think it's worthwhile. It's essentially a prediction about the future. But when economists say things will be bad, investors hear it and refrain from investing, and the prediction becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

I have serious grievances against my economist friends - of whom I am one - that they acted very irresponsibly. They didn't look into the specifics of the reform, they just listened to the cries from the left. Most economists themselves lean to the left, and they didn't need to do that. I truly don't understand them. These discussions are fueled by a lot of emotion. Ideology has overshadowed expertise."

"The damage has already been done," says Aumann. "An economic crisis may occur due to the self-fulfilling prophecy."

Is it reversible?

"In the end, I believe that the markets will recover and realize that the situation is not so terrible, despite the prophecy, and people will jump on the opportunity to buy cheap and return to investing. As Roosevelt said, we have nothing to fear but fear itself."

So, is this prophecy coming because everyone dislikes Netanyahu?

"Yes."

And perhaps it comes from a fear of becoming a country like Hungary or Turkey?

"But we don't want to be like Turkey. They say 'Turkey! Hungary!' without looking at the details - we want to be like the United States, where the president appoints the judges. We want to move closer to that."

Even the United States is against the reform.

"That's because they want to overthrow the government, and that could happen."

But there have been right-wing governments in Israel for decades. Netanyahu himself is no Johnny-come-lately either.

“It is due to the strong opposition of the left. [U.S. President Joe] Biden and his advisors don't delve into the depth and details; they just hear the outcry from the left and say, 'We stand with the left.' The reform doesn't bring the country closer to dictatorship."

Aumann spoke at a Knesset's Constitution, Law, and Justice Committee hearing but does not participate in protests.

While Kahneman resides in New Jersey, he joined the protests in Tel Aviv during his visits to Israel. "The prominent thing for me was that it was a joyful protest," he says.

"People didn't come out of a sense of obligation. They came because they wanted to be there. There is a feeling of unity, fraternity, a very special group. It's not the entire nation, but people discover that there are others like them. The issue of flags is significant. Symbolically, it represents unity around the flag. It carries a lot of meaning. There is no doubt. The flag has almost become a symbol of the right. Now it's clear that they are fighting for the soul of the people. It's a joyful protest. Much more than angry."

The question is whether this is a good thing. Perhaps joy brings about less change than anger.

Kahneman: "It's a good thing. Joy promises perseverance, and it stems from people truly believing in what they are doing. And it has been going on for so long that there is a feeling it won't fade away. If it were out of a sense of obligation, then it could have faded. But it doesn't fade. It's very impressive."

It doesn't fade, but there is a feeling that it's somewhat diverging. The protests began against the judicial overhaul, and now they're shouting about the constitution, equal burden, and more.

Kahneman: "I estimate that the further it moves away from the judicial overhaul, the less participation there will be, and it will be less joyful. There's no doubt. The public that is caught up in the issue of judicial overhaul is not entirely united on other matters, mainly regarding equal burden. It's quite natural. However, there is less urgency in this matter compared to the legal issues. It's a less passionate subject, no doubt."

"It's a struggle for the soul of the people," says Kahneman. Even in this regard, Aumann agrees: "He says wise things. But even if there is a culture war, it should be conducted in a civilized manner. Democracy requires that the majority rule the Knesset, not turning the streets into the Knesset."

One of Aumann’s most controversial positions relates to what many on the other side see as the main motivation for the reform: Netanyahu's legal woes.

"I think we should be like in the United States," says Aumann. "It is impossible to conduct a criminal process against a head of state like against any citizen. It should go through a political process like impeachment, with a large majority, and then to court.

The founding fathers of the American nation understood that it is impossible to separate a criminal process against a head of state from political considerations. Therefore, approval from an elected body is necessary. Here they accused the head of state, and it is impossible to separate it from politics, and then everything got complicated. I already hear people saying, 'Reform in exchange for justice' - that is corruption on a much larger scale than any accusation against him. They mixed up the justice system with politics, and that is forbidden."

Prof. Kahneman, we discussed international pressure. In that regard, one of the great hopes of the resistance to Israel’s presence in the West Bank was that international pressure on Israel would cause it to stop. Now we are seeing a sort of reverse effect, that international pressure on Israel will cause it to resist or halt the reform. Aren't we relying on something that won't happen here?

Kahneman: "I think the pressure regarding the reform is immediate. There is a sense of irreversibility, something that has never been seen before. In the case of the two-state solution, we never had to take immediate action because otherwise, it would never happen. The current crisis mobilizes many more people because it is irreversible."

So, are you saying that global pressure will help in this case?

Kahneman: "There are politicians in the country who are not bothered by international pressure, and they are not few, because 'who cares what the gentiles think.' But in Israel, there are many, even on the other side, who see Israel as part of the Western world, and they will have a significant impact."

Do you see this in your field, in academia? Do you encounter pressure?

Aumann says no. Kahneman says the opposite: "I can talk about what is happening in the United States. I imagine it's similar in Europe. The image of Israel has gradually and negatively changed for at least 20 years. What used to be the stronghold of the far left, the sympathy for the Palestinians and the hatred of the occupation and so on, today it seems to me that it is true among the majority of students at leading universities and within the Democratic Party. It is partly a conscious result of Benjamin Netanyahu's decision to rely on evangelicals."

In your opinion, what would be considered effective international pressure?

Kahneman: "Well, what will happen is mainly a decline in the reputation of Israel. Being Israeli used to be a matter of pride. Regarding the occupation, it becomes complicated, and you can't be proud everywhere. But if the reform were successful, being Israeli would be something to be ashamed of. In academic circles I know, they expected an Israeli to want to leave and not live under such a regime."

"If he is ashamed," Aumann interjects with a smile, "he is welcomed to return to Israel."

"I remember times when saying 'I'm Israeli' was something you would say with pride," says Kahneman. "Losing that is a great loss. In my opinion, this feeling is part of what drives people to protest, so the protest is joyful: people are rediscovering what it means to be a proud Israeli. Just as they reclaimed the flag, now they are reclaiming national pride."

Looking ahead, to the future, are you optimistic about the country's future?

Kahneman: "I am genetically pessimistic, about everything. Even my mom was pessimistic. I don't see, and I don't think anyone sees, a good forecast on this matter. Hope is something else. I don't have much hope. I haven't heard anyone with a realistic idea for a good ending to this story. There is no vision."

Aumann: "No. I am naturally pessimistic. The situation is very severe. The current period is difficult, but come on, I'll give you a glimmer of hope: we have already gone through much harder things. I think in 20 or 30 years, we will look back at this period and say, what were we complaining about? About attorneys general?"