In the early morning hours, the first group of immigrants arrives at Jacumba Hot Springs, a small town on the Mexico-California border 75 miles from San Diego. The famous border wall that was supposed to stop illegal immigrants from entering US territory stops right here at the edge of the mountain on land belonging to Jerry Shuster who immigrated himself from Yugoslavia in 1969.

In recent months, thousands of immigrants have crossed the border over his land, leaving in their wake a great deal of trash, water bottles, torn passports, and papers. He has complained to both the border patrol as well as the sheriff’s office about the immigrants lighting fires and destroying fences but has been told that nothing can be done. In the past, immigrants would secretly sneak in, carefully evading the border patrol. Now, they know no one’s going to throw them out.

This is a 180° turn for the border patrol. Whereas in the past, they were supposed to protect the border from infiltrators, arrest and deport them back to their countries of origin, they’re now obliged to receive them with open arms. This reception includes hotels and absorption centers where they receive three meals a day, diapers for their babies, medical treatment, clothes, and anything else that might need to ease their acclimatization

After a four-and-a-half-hour journey from LA in heavy morning traffic, I get to the town just in time to see how, like a well-oiled tour operating company, the Mexican smugglers drop off the immigrants on the southern side of the fence, and are then off again to bring the next group.

This is a very lucrative business earning the Mexican cartels millions. How lucrative you ask? $1 billion per month from smuggling goods, people, and drugs. They use the money to buy more sophisticated guns to consolidate control over their territory in Mexico and beyond, produce Fentanyl, market it from China, or sell it in the US. Everyone knows this business’s days are numbered and that the party will be over one day. Until that day comes, they want to make as much money as possible.

A group of 20 migrants with backpacks was making its way along a sandy path to the camp on the edge of the town. From a distance, they look like a group out on a trek. The border patrol vehicles and officers accompanying them on foot say otherwise. Five minutes later, they reach a makeshift camp – an open space surrounded by bushes and a great deal of trash left by previous immigrants. They’re handed fliers in every possible language reading “Welcome to the USA.” They diligently read them, trying to understand what’s next for them.

A feeling of total confusion prevails among the immigrants. Except for two young men from Georgia, hardly any of them know any English. They come here from across the globe – Ecuador, Peru, Mexico, Honduras, Brazil, and even a woman from Italy. It’s unclear how she might get refugee status, but it’s worth trying. Vanessa, with long orange hair who was donning a woolen hat, came from Brazil with her husband Pedro. She immediately tells me she’s pregnant and, maybe to prove it, raises her shirt revealing her belly.

What month are you in?

“Eighth,” she says with a big smile. “I told them I’m pregnant, so maybe they’ll take us out first.”

Then, in a mixture of Spanish and Portuguese, she tells me that she and her husband set off on their journey 15 months ago and that they paid $15,000 to get to the US. They don’t specify who they paid exactly but, in all likelihood, they mean the “coyotes” – as the smugglers are colloquially known. Coyotes work in collaboration with the cartels transporting immigrants in their territory along the border.

Wasn’t such a long journey hard for you? And you’re pregnant.

“Yes, but I was treated very respectfully and they helped me a lot.”

Vanessa and Pedro sold everything and got help from their parents to obtain the money needed.

The rates the smugglers charge are subject to the country of origin. Most pay $7,000 - $15,000 per person, depending on which country they’re coming from. Those coming from other continents, such as China, pay more – sometimes up to $50,000. The price is also determined by the chosen “package.” You’ll get food, transport, and a place to sleep if you pay more. Those without such a budget make their way by foot, mainly until they reach a place from which their “tour guide” takes them to the border. Those crossing the Texas border via the Rio Grande are given colored bracelets helping the cartel keep track of how many thousands of dollars they still owe.

5 View gallery

Trying to figure out exactly what is going to happen with them. Migrants with the flyers they received after the border crossing

Some of the immigrants don’t have the whole amount to pay the smugglers, so they pay a deposit and agree to work and pay the rest after reaching their destination. If they don’t pay, they risk murder or kidnapping. Horrific tales of rape and sex trafficking of women and children unable to pay their debts are plentiful. Cartels also take hostages demanding ransom fees from their families.

It's not just the cartels dangerously standing in their way. In the summer heat of June 2022, smugglers were transporting migrants in a closed truck with no air vents. After crossing the border, the truck was abandoned in San Antonio, Texas and the lifeless bodies of 50 immigrants were found in the truck. A further 16 were found unconscious and hospitalized.

Ecuadorian brothers Raoul (33) and David (29) made their way by bus, boat, and then on foot. “It is dangerous, but staying in Ecuador is more dangerous. We saved up for three years to make the journey. We have family in Connecticut, so we’re hoping to go there.”

Alejandro (31) from Peru was trying to keep warm by the bonfire. There was a cold wind blowing and there weren’t enough tents for everyone. “I hope they’ll come to get us before nightfall,” he says. He couldn’t afford to bring his wife and children, so he made the journey alone. He doesn’t know when he’ll next see them but hopes to start earning soon to bring them to the US. “My children are little and the journey would be hard for them now, but it’ll be easier in a few years when they grow. I’ve heard of children who died on the way or got sick. It’s scary.”

When I ask him if he wants to live in California, he asks quite innocently “How far is that from here?”

He’s not alone in not knowing where he is exactly. They just know the smugglers helped them make it to the United States.

5 View gallery

If they don't pay, they risk kidnapping or murder. Migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border

A group from Georgia was trying to reconstruct a tent left behind by earlier immigrants. Matta (28), a bearded young man in sunshades tells me he was a boxer in Georgia. “I sold my apartment to get here” he explains via a friend serving as interpreter. “I now have nothing, but I’m happy to be in America. My dream is to become a boxer and make lots of money” he says. “In Georgia, I couldn’t leave the country for matches. I felt I couldn’t move forward.”

His friend adds “The Georgian government is very corrupt and life is very hard financially. There’s no work, and even when there is, you can hardly make a living. We had no other way of getting here. We couldn’t get visas, so this was the only way and it was very expensive. I got here with nothing but this bag, but it was worth it.”

At around 1 pm, the day’s second group of immigrants arrived. Like the first, it included many from Latin America, Turkey, Georgia, India, and China. Except for the Chinese, who didn’t want to be photographed, they all happily agreed to be interviewed and for me to take their pictures. In 2021, only 342 Chinese immigrants came across this border. This year, it’s up to 37,000.

Using a translation app, Chan from Beijing tells me he learned where to get into the US from by watching videos uploaded to TikTok by other immigrants. It’s not just the Chinese who’ve been using TikTok to figure out how this business works.

Maybe due to language issues, maybe due to fatigue, the immigrants don’t talk to one another – even those from the same country. Some sit by the fire trying to warm up a little. The first to arrive move into the tents as the others hang around waiting to see when they’ll be picked up.

They’re doing much better than those arriving two or three months ago who had to wait several days in the camp before buses came to collect them. At its height, 700,000 immigrants were showing up each day. They built tents and small wooden tarp structures now being used by the new wave of immigrants. In December 2023, there were only two portable restrooms here. Now there are four sinks with soap and a huge water tank.

Before dark, by which time it’s already very cold and windy, a bus arrives to pick them up. The relief on their faces is clear. They line up and get on the bus to the absorption center where they’ll register. Those not remaining in California will probably fly on to sanctuary states such as New York, Chicago, or Colorado.

The most recent wave of immigrants at the border will become a central electoral issue and may well decide it. Many Americans, even Democrats, would be only too glad to finally see an end to mass migration across the border. The Biden administration is expected to unveil a series of executive orders securing the US’s southern border. In so doing, the administration will transfer responsibility to Republican support for legislation redressing the troubled immigration system.

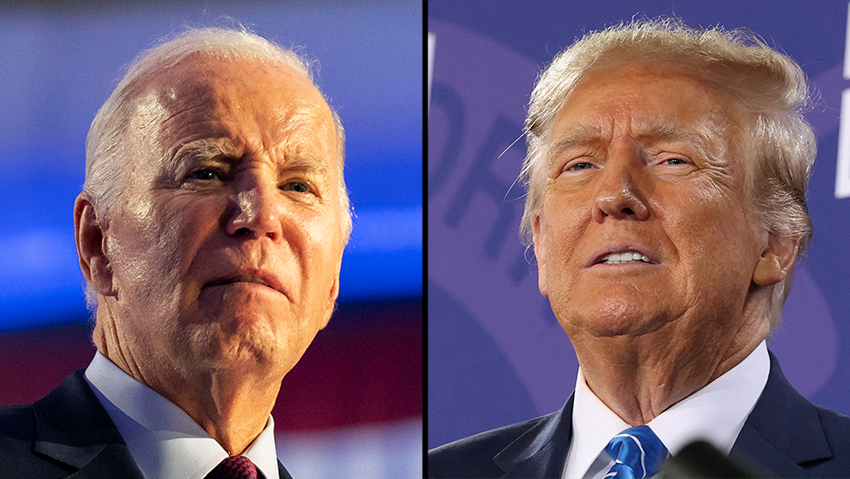

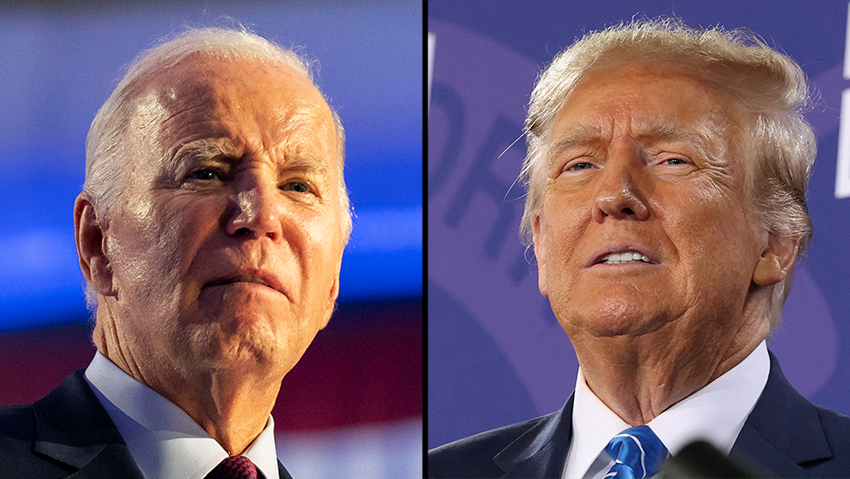

5 View gallery

Immigration is one of the main issues on the election agenda. Trump and Biden

(Photo: Alex Brandon/AP, Stephanie Scarbrough/AP)

If elected, Donald Trump has promised to launch “the largest domestic deportation operation in American history” using the military to round up undocumented immigrants into camps and implementing large-scale deportations. Republicans claim that Biden’s policies are responsible for criminals, drug dealers, and even spies entering the country. Trump further claims that the Democrats are encouraging immigrants to freely flood the country so that they can vote in the 2024 elections. He said that most of the immigrants don’t speak a word of English and that the Democrats register them anyway.

Meanwhile, the completely open border is working in favor of several interests: Employers wanting to employ immigrants on low wages; government contractors scoring contracts to house and transport, and; service providers such as hotels and restaurants charging particularly high rates.

The economic burden on asylum cities in which the immigrants end up is huge. In New York, in high demand for immigrants, hotels (including the historic, former 4-star Rosevelt Hotel in Manhattan), have been turned into emergency shelters. Mayor Eric Adams provides immigrants with meals costing $64 per day and plans granting every immigrant family food stamp cards to the value of $1000 per month. Reports claim that New York City pays $200 - $310 per night to various hotels. DocGo, a company providing health services, won a $432 million tender from New York City to supply meals and services to 4,000 immigrants. The whole story is costing the city billions of dollars.

Last year, the city paid $4.3 billion on providing food and accommodation to immigrants and, by the end of 2024, is expected to spend $12 billion on funding accommodation for 173,00 illegal immigrants whose numbers are expected to rise. City residents will be paying the price. Adams announced he'll be forced to cut budgets for schools, police, and seniors as the city is collapsing under the burden.

It's no better in other asylum cities. Shelters in Chicago are full of illegal immigrants. Left with no choice, some slept at the airport until they found a place. Denver has taken in tens of thousands of immigrants, filling the centers as American homeless sleep on the streets. Texas governor Greg Abbott is sure to bus the immigrants across state lines to Chicago and Colorado. As 300,000 illegal immigrants crossed the border into Texas in December 2023, Abbot announced the state was in a state of collapse and described it as an invasion. When the mayor of Chicago impounded the buses from Texas to stop sending immigrants, Abbot said “No problem” and flew them there instead.

Oh, and in the United States, they don’t call them “illegal immigrants” anymore but rather “asylum seekers” or “new immigrants.” President Joe Biden was rebuked for his State of the Union address in which he referred to an immigrant from Venezuela who murdered American student, Laken Riley, as an” illegal.” He later corrected himself saying “I shouldn’t have used the term illegal. It’s undocumented.”

Meanwhile, in Jacumba, they’re troubled by the fact there are many criminals among the immigrants. The border fence runs a few short feet from Jerry Shuster’s neighbors, Barbara and Robert’s yard. “What worries us mainly is who these people are. We don’t know if there are drug dealers among them, how many of them are wanted criminals in their own countries, how many are terrorists” says Robers. “Most look like straightforward, regular, good people, but you can’t tell. One immigrant from Africa connected to a terrorist organization has already been caught. There were also murderers and people traffickers among them.”

5 View gallery

Eric Adams. New York City spends a lot of resources on behalf of immigrants

(Photo: AFP)

In the town’s only grocery store, I met Aleen Brown who moved to the town with her husband 38 years ago. “What worries me the most is where does the country have money to fund this immigration from. Some of these people are wretched and are entitled to refugee status, but a lot aren’t, and they’re a burden to the US. Our taxes go to fund immigrants, not to infrastructure or to our towns that need help. I immigrated here myself, but I did it legally and I didn’t get any gifts. “

Jacumba is a poor town. The town’s young folk have left and most of the population is older. The town’s only school closed a few years ago as there weren’t enough children to fill the classes. Until a few months ago, no one had heard of this small town in the middle of nowhere. When the first wave of immigrants started arriving at the end of last year, journalists and TV crews flooded in along with charity and humanitarian aid workers offering the new immigrants food and water. They’ve stopped coming and all that’s left are the empty water bottles strewn among the bushes.

Not all immigrants cross the illegal border. Some, mainly those with small children, cross at the official San Ysidro border in Dan Diego and fill out application forms for refugee status. Perhaps they can’t afford to pay the smugglers or are wary of the difficult journey. The problem is that some are forced to wait six months, in which time they sleep in tents in Tijuana on the Mexican side of the border, before receiving permission to enter the promised land.

By both American and international law, anyone arriving in the United States can apply for asylum. They’re screened to decipher whether their fears of persecution in their home countries are founded. Their cases are then transferred to the courts for a decision as to whether they may remain in the US. This process, however, can take years and until that happens, they’re free to operate freely within the state. If they suspect their application will be denied, they simply don’t show up for their court hearing and remain in the state illegally.

Before leaving, I returned to the camp at 8:30 am the following morning. There’s already a new group of 15 immigrants, including a couple with an eight-year-old girl and a ten-year-old boy.

When did you get here?

“An hour ago,” Carlos responds in Spanish.

How long have you been walking?

“Seven hours. We walked all night.”

A woman of about 40 dressed in a coat and hat covering her hair and eyes, complete with false eyelashes, approaches me. She tells me she’s from Brazil and that she made the journey alone, with no friends or family. Her eyes are shining, perhaps from fatigue, perhaps because of the wind. “Do you know when they’ll come to pick us up?” she asks, warming her hands at the bonfire. “In a few hours,” I say enthusiastically. “Welcome to America.”