Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

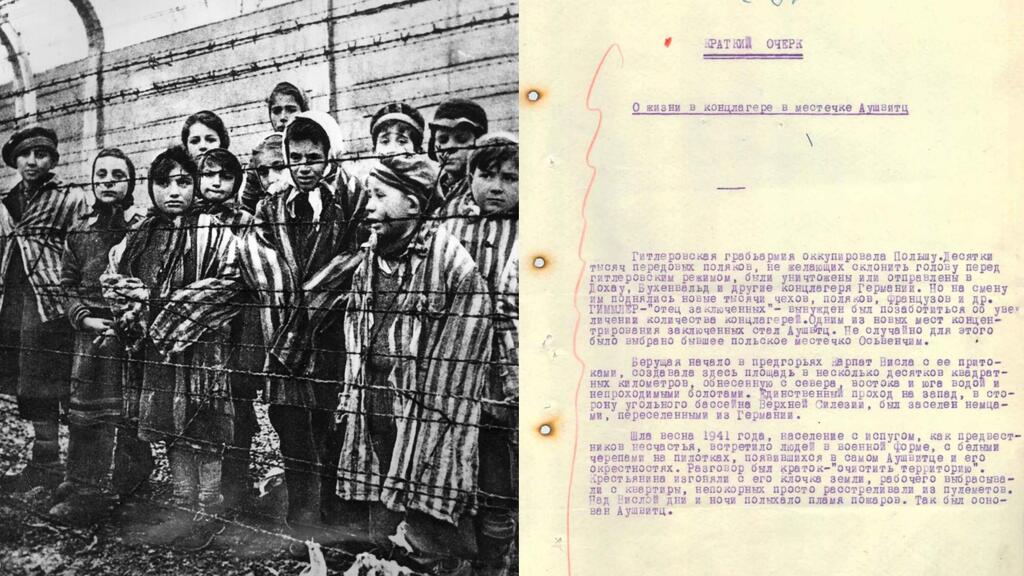

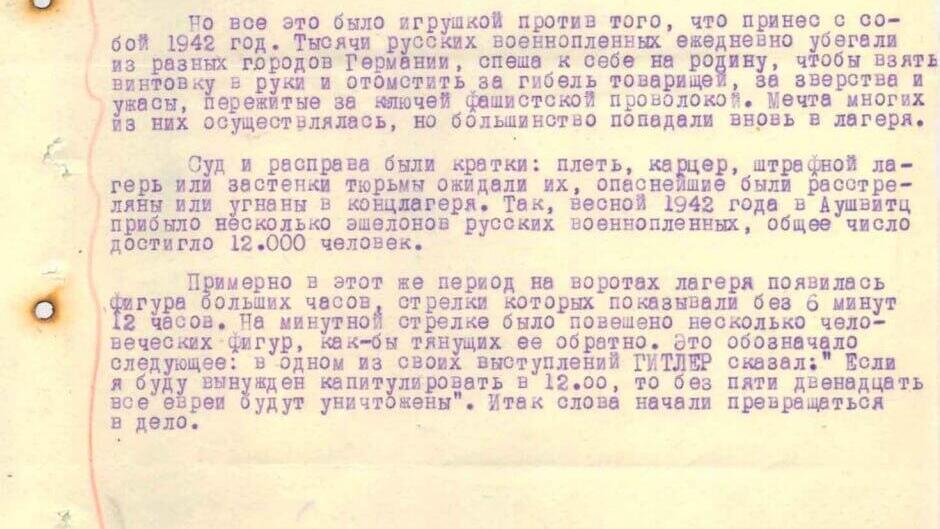

Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) recently declassified an 80-year-old document containing the blood-curdling account of a Soviet prisoner of war who was imprisoned in the infamous Nazi death camp Auschwitz-Birkenau and managed to escape.

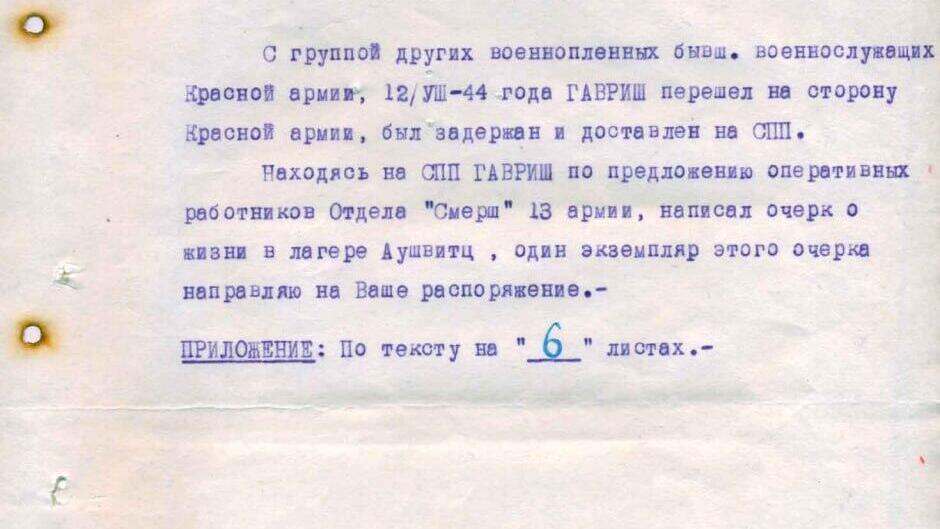

The Soviet officer, Senior Lieutenant Pavel Gavrish, said in his memoir that he directly witnessed the horrors unfolding in the camp and was asked by counterintelligence officers to put his experiences in the camp into writing in the form of a short essay penned on September 8, 1944, under a "top secret" classification.

Gavrish was born in 1917 in modern-day Dnipro, Ukraine. According to his writings, he arrived in Auschwitz after falling captive to Nazi forces.

He details how new arrivals at the camp had serial numbers inked on their bodies: prisoners of war on their chests and other civilians on their hands.

"Together with political prisoners, robbers, murderers and pederasts were thrown into the concentration camp, who were instructed to maintain internal order in the camp," he wrote.

According to Gavrish, the camp’s commanders would appoint Polish and German prisoners who were serving sentences for banditry, murders and robberies to maintain order, doing so with unusual cruelty.

The camp's leadership set its goal on the mass extermination of the prisoners. Some 12,000 famished prisoners were forced to partake in the construction of the facility under harsh conditions, hundreds of them perishing every day. Only 140 survived.

“Only some of the prisoners were tasked with the construction of the camp, the rest of the jobs were completely unreasonable. Each kapo (prisoner functionary) was tasked with exterminating a certain number of prisoners. When they returned to the camp each team would lead a funeral procession of 50-100 bodies," he wrote.

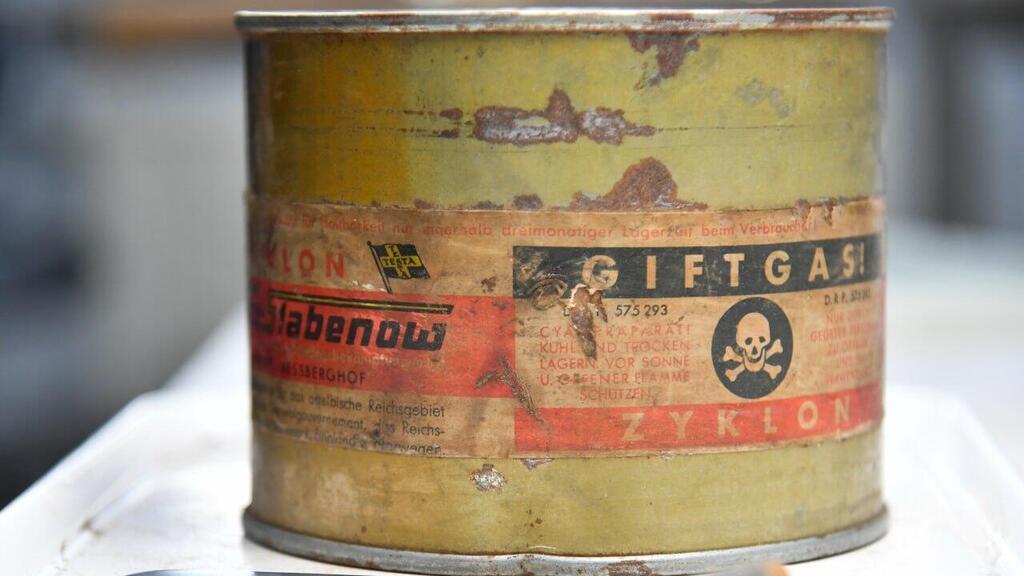

"The stench of burning bodies was vile"

Gavrish noted the kapo and the Poles were most eager to get rid of the prisoners. Whoever did not work or was sick was sent to the crematoria. He added that the camp had a hospital to which hundreds of prisoners were sent every day, but only a few ever returned. “At the edge of the camp, there was a house next to which ditches were dug out. On top of them were placed thick metal wirings.”

“They’d place people inside of the house, and kill them with gas,” he wrote. “Not everyone was able to fit in the house, because it wasn’t big enough, and the number of people that arrived there was great.

“Whoever wasn’t able to enter was murdered outside with axes and shovels. They’d place the bodies on the metal wirings and burn them in the pits day and night.”

Gavrish further wrote that the stench of burning bodies was vile. “Those who worked there would be replaced every two weeks due to the gruesome sights. It lasted until about late 1942, when the construction of the crematoria was finally completed.” The Soviet officer notes that three-four bodies would be stuffed into a single burning chamber at once.

"Murderous orgies"

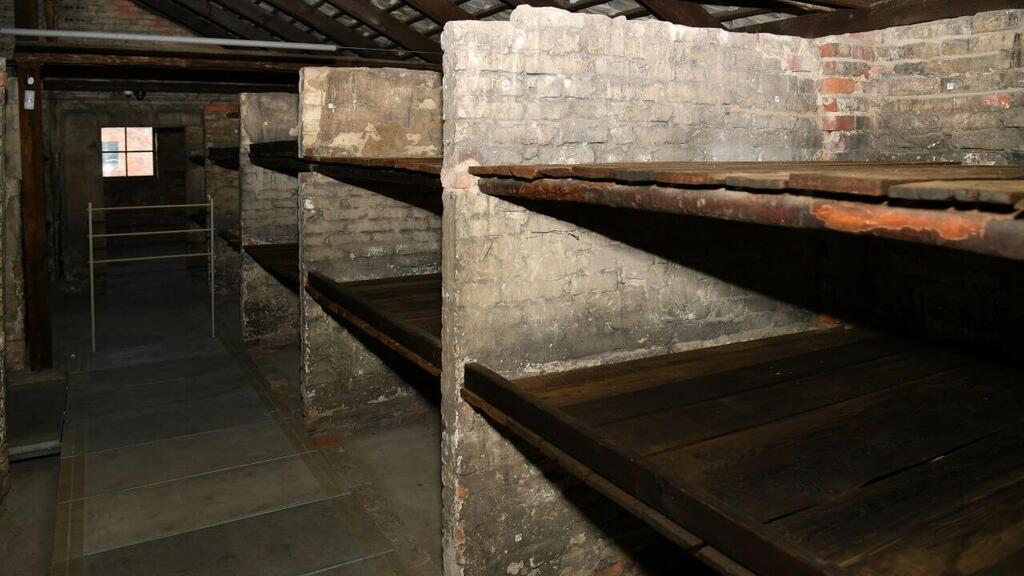

Gavrish also describes how he would wake up each morning to find some 20-30 prisoners hanging in each one of the camp’s cabins, and that whoever killed more prisoners were treated better by the commanders.

The prisoners were subjected to endless torture and bullying by the Nazi officers who would whip them for sports. Intoxicated SS officers armed with machine guns and whips would embark on "murderous orgies", surrounding a cabin and killing half of the prisoners in it.

Gavrish also described how Nazis would select which prisoners to kill. “Naked prisoners were hauled into cabins and inspected by an SS doctor who picked the scrawniest and weakest of them. They would then be sent to other cabins where they were held for 3 or 4 days without food or water.”

“Later they would open the cabins and place the prisoners onto trucks like firewood and transport them to the crematoria,” he wrote. “They would do so to groups of 3,000-5,000 people each time.”

The Soviet officer also described how prisoners would be sent to “penal cabins” for the slightest infraction from which only a few ever returned.

In one of his horrifying accounts, he details a massacre that took place in the camp on Christmas of 1942. “The Germans love to celebrate holidays. The whole camp was carrying rocks from one place to another. Back and forth, running, on both sides of the road. An SS officer would stand about a meter or two away with a club in his hand. Whoever did not run fast enough was beaten. Over 3,000 people were killed or injured on that holiday. Hitler’s birthday was marked by the murder of ten Jews and one soldier.”

Gavrish also described: “Around that time (spring 1942), a big clock was placed on at camp gates showing the time at 6 minutes to 12. Human figures were hung on the minute hand, preventing it from hitting 12. Hitler said that were he forced to surrender by 12pm, all of the Jews would be annihilated five minutes prior. His words began to turn into actions in Auschwitz.”

Russian revenge

Gavrish’s fate remains unknown. In 2014 his granddaughter resumed the search for him in different forums but to no success. After giving his testimony, he was likely recruited to a Soviet penal unit — as happened to many prisoners of war who returned to the Soviet Union and were suspected of surrendering or treason — and died in 1945. Information about his fate was never relayed to his family.

Gavrish stressed in the document the functionaries at the camp were German and Polish. Reporting on the document, Russian media chose to focus on the reports of Poles being involved in the horrors of Auschwitz. However, historians note that the release of the documents wasn’t done in pursuance of historic justice, but rather as an attempt to take revenge on Poland for its persistent support for Ukraine in its ongoing conflict with Russia and for sending tanks to its war-ravaged neighbor.

Academic institutes who work to collect records of the Holocaust say that “Russia is unwilling to talk about war crimes of countries who are cooperating with them. Russian archives are the hardest to enter in Europe, so they didn’t release the report to encourage research and discussion.”

Alex Tenzer, a social activist and descendant of Holocaust survivors, says that “ever since the begging of the invasion of Ukraine Russia is releasing documents in order to prove the Polish and Ukrainians as pariahs. It’s upsetting that Russia released this document only now and is using it out of political necessity.”

Tenzer demanded that “Russia should every testimony it has. We can’t allow the memory of the Holocaust to become a political game. The arrival of Russian testimonies to Yad Vashem will aid in studying the Holocaust and allow thousands of families to know the fate of their loved ones.”

Yad Vashem archive manager Masha Pollak-Rosenberg, warns that the Russian officer’s testimony should be read “carefully.” She adds that Soviet prisoners who were captured by the Nazis were interrogated and often suspected of aiding the enemy. “Many of them were sent to the gulags or to penal battalions, who were used as cannon fodder.”

She adds the testimony could have been an attempt by the officer to save himself. “Testimonies from captives and prisoners don’t add any new information. Soviet inquires also detailed details from death camps and testimonies of captives held there.”

Pollak-Rosenberg also explains that Russia had released a statement to the Allies detailing the death of Jews by the Nazis, even naming Babi Yar, where thousands of Jews were killed. “Does this change history? No, the West saw this statement as a Soviet move in order to begin an offensive on Germany.”

According to Pollak-Rosenberg Jews in the U.S. have also pushed for the U.S. and UK to get involved, however, the greater aspects of the war led Allied forces to ignore the murders, not launching a front in Europe before 1944.

“Are the Soviet Union and others aware of it? Yes. Does it change their priorities? No, the war is fought only in strategic positions marked by the Allies.”

She adds that Gavrish’s testimony adds to the list of Nazi camp prisoners who survived. “There are many similar testimonies that are published for many years. We need to contextualize published material by Russia over the last year with the current event and ongoing war.”