Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

It's midweek at a military base in central Israel. Prior to the evening, trucks arrived at the base's gritting facility, carrying thousands of hard drives and disk-on-key devices containing highly classified information from the prestigious Unit 8200. The mission: to delete and destroy any piece of information existing on these chips.

More Stories:

Those in charge of the mission: seven soldiers with special needs responsible for the destruction of classified materials in the 8200 branch, overseen by Chief Warrant Officer David (not his real name), in a unique and particularly moving collaboration.

4 View gallery

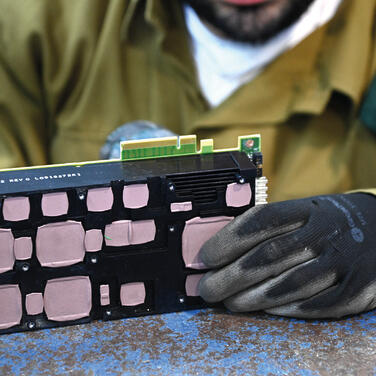

Seven soldiers with special needs are responsible for the destruction of classified materials in the 8200 branch

(Photo: Yair Sagi)

"We are the storage facility for the entire Unit 8200," declares David, pointing with his hand to the factory behind him, where heads are bent, hands are busy and the sound of drills fills the air. "We also receive the equipment purchased by the unit, store it, and transfer it to the various units' branches. But our main task is to conduct the scrapping process for equipment that needs to be decommissioned and destroyed."

"When I arrived here as a child in '87, I was also assigned to the scrapping chain. When classified equipment arrived, we would take the equipment south and bury it there. With time and advancement, and with the need to care for the environment, the IDF was asked to find a smarter solution. The additional solution was to outsource the scrapping process to external companies. However, as the intelligence and equipment became more problematic and classified, they wanted to keep everything within the IDF, including the destruction process. So, what do we do? Store it? Try to destroy it ourselves? There was always a lack of manpower. Initially, I and a small team from Unit 8200 did everything with old machines. We would work tirelessly, finish late and the machines would often break down. Eventually, while we were thinking about a solution, the NGO Akim came with a request to the IDF: to integrate people with special needs into army units," David explains.

Love to disassemble things

The pilot for integration set off 10 years ago. "We worked hard to succeed in integrating them here. Today, I have an amazing team, of professionals, friends and family. Soldiers who come here independently or with the help of their families and contribute everything they can to the army," according to David. And then he gives us a very emotional and secretive glimpse into the "Equal in Uniform" project's activities.

We follow David through the gates of the scrapping factory. Piles of shiny equipment pass by us behind huge signs labeled "Classified" and "Top Secret." Behind the stack of equipment, in a modest and particularly noisy room, the soldiers sit in David's office . They are very excited about our arrival but they don't stop working for a second.

I take a hard disk drive in my hand and start going through the the intricate dismantling process, one by one. "Nice to meet you, I'm Shai, 33 years old from Tel Aviv," a volunteer on the autism spectrum, holding a large screwdriver, introduces himself. "I live with my mom and dad. I really love taking things apart, and that's why I love being here, and I also love playing on the computer, which goes along with what I do here. Come, let me teach you. First, we need to remove all the screws from the computer drive and search for the hard disk that contains everything we're not supposed to keep."

What do you enjoy the most here?

"I love learning new things. I want to be like all the soldiers in the army, at the highest level. My memory is very good. And what I love most about myself is that I'm determined. No matter how many computers they bring me to dismantle in a day, I don't get discouraged. I've been here for seven years, and I enjoy coming every day. The secret to doing a good job is that you don't have to exert any force. And I love listening to music, especially Eyal Golan's songs."

After we finish opening up the computer, we move to L., a 20-year-old from Herzliya, who is also a volunteer in the IDF, waiting for us before starting to dismantle another part of the computer.

"I have a big brother who served in the Combat Engineering Corps in the south, and I wanted to enlist like him. I've been here for almost two years. I was in a different unit before, but I didn't find myself there, and then I transferred to another unit, but I didn't fit in there either until we decided together that, for me to be happy, it's better for me to come here, and since then it's been a whole different world. I come to work with a smile, I enjoy it and have fun. I love the people, I love my commanders, my friends, and even the work. I learned everything here from my friends and my commander David. Before I came here, I had never seen a computer open up like this. I learned how to disassemble everything, computers, servers and monitors. I dismantle everything quickly."

What is most important in such computer dismantling? In such classified and important work?

"To be attentive and to look everywhere to find another hidden pin or another screw that can be dismantled. Concentration is necessary, and I have a lot of it."

Working odd hours

E. is the assistant of David. He didn't want to enlist in the army at all, but he ended up spending a day at the factory alongside the determined troops, and since then he decided that he not only wants to enlist and serve but also hopes to stay and work as a civilian employee in the IDF in this place.

"I'm 22 years old from Alfei Menashe," he says. "I have two younger brothers, one of them is also in the army, in the Golani Brigade. At first, I didn't want to enlist, my plan was to get out after the first month. I didn't like it, I didn't find myself. But then they told me to come here and look around, and I fell in love. I stayed, and it's been a year after my discharge date, but I'm getting a salary, and I still have more time here, I believe. There's an amazing feeling here, a sense of family. I come here at odd hours, and I leave here at odd hours because that's my joy. It's what makes me calm the most, more than anything, and the people here keep me company. If you tell me to sit at home on the computer, I'm not capable, but the dismantling here makes me feel good. I arrive at 7:00 a.m. and leave last. I dismantle everything that can be dismantled. I understand the meaning and know my role in this place. I am the last line of defense in the IDF, and if we are breached, the classified information could be leaked, and I won't allow that to happen ever."

Give me an example of a problem that arose during one of your dismantling processes.

"One of the problems we had was the hard disk with a lot of information on it, but it was damaged and difficult to destroy. We thought about how to deal with it. It wouldn't fit in the paper shredder, so we realized that we needed to grind it in a special machine that we brought specifically for that purpose. Over time, things just become smaller and more problematic. We find hard disks in devices that no one even knew existed there. It's the strongest defense and the greatest satisfaction it gives each of us. And we learn everything on the job. Every day I can be surprised by something else."

Next to E. stands B., a deaf-mute person whose parents searched for a suitable framework for him in the army for a long time until they arrived at the factory and knew it was the right place for him. "I feel everything," B. writes to me via a WhatsApp message. "I feel the drill even though I can't hear it, I find a way to communicate with the guys here despite being mute. We have strength together."

David adds: "There are many things we rely on each other for. For example, B. can't hear the drill, and if the drill grinds the screw, it can't be removed anymore. You can only understand that through hearing. So we know to alert him, in time and for safety reasons, he always works in a team as well."

The last two in the chain are A., who sorts everything they've dismantled so far into recycling, waste, and scrap, and then passes it to R., who is also the only woman in the factory and is in charge of the most important grinding machine in the chain.

"I'm from Ra'anana, and my dad is also a lieutenant colonel, and I wanted to follow him to the army and volunteer," says A., 20. "I enlisted in Unit 8200, and since then I've been dismantling, assisting with machines, but mainly sorting, doing what needs to be done. I contribute to the country, I take care of the soldiers, and they measure things there. That's what I wanted to do the most. I enlisted, put on the uniform, received a beret, and I'm so happy to be like my dad."

R., a resident of Netanya, inserts the hard drive she received from A. into the advanced and particularly noisy grinding machine. She waits for the correct sound before inserting the next one. "I arrive alone on the bus at 7 a.m. and stay here until 4:30 p.m. I was one of the first in the recruitment program 10 years ago, and here I am for about a year. I'm already a civilian working for the IDF, the first with special needs. And this is my machine where I dismantle sensitive items. Once it goes in, there's nothing we can do with the material or even identify what it is."

"Look at the size of this hard drive, and look at this," she shows me one small and one exceptionally large. "These are from the past, and these are from today. I've seen it all. And our machine dismantles everything. I insert them at my own pace, one by one, making sure nothing gets stuck, and move on to the next. Because the machine can get stuck. That's the most important thing. On the other side, everything gets shredded into pieces. And everything goes for disposal to the recycling corporation responsible for recycling in Israel. Patience is required."

David interjects, "B. also operates the machine even though he's deaf. He puts his hand and feels when something comes out from the other side. He replaces me when needed. Yesterday, there was an operation with thousands of hard drives that arrived, and after two days, we finished dismantling everything without any issues."

From the small but significant factory, David and his colleagues primarily want to convey an important message: "There is no shortage of work in all areas of the army," explains David. "We need more manpower, not just for ourselves but for the entire army. These soldiers here teach us and assist us in an exceptional way, and I call upon and ask every family that is undecided about sending their children to the army, to send them to us. It will be very helpful and will be good for everyone's well-being."