Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

For two decades the combination of the words "Hamas Tunnels" has been considered a nightmare for Israelis. Such a tunnel exploded underneath the JVT outpost at the Philadelphi corridor in 2004, killing five soldiers. Such tunnels were used for the kidnapping of Gilad Shalit and the bodies of Hadar Goldin and Oron Shaul.

At Operation Protective Edge in 2014 Nukhba terrorists infiltrated Israel via such underground tunnel dug from Gaza into Israel, and they were recorded killing Israeli soldiers. On the morning of October 7, 2023, when hundreds of Israeli abductees were being dragged or marched into the Gaza Strip, all Israelis cringed at the thought that within minutes they would be led tens of feet underground.

A year has passed, and the horror has not faded. In some respects, and certainly after presenting videos of the dark tunnel where Hersh Goldberg-Polin, Eden Yerushalmi, Ori Danino, Almog Sarusi, Carmel Gat, and Alex Lobanov were murdered at the end of August, the fear has intensified.

And yet, since the onset of the ground maneuver about 11 months ago, we know much more about the massive underground network that Palestinian terrorist organizations have dug under the Gaza Strip over the years. This was made possible due to the countless hours of IDF soldiers operating inside it, but tragically more so, thanks to firsthand stories of hostages who have returned, helping to shed light on the life, if you can call it that, inside the tunnels. Here are monologues by five people who summarize what Israel knows about the most significant strategic asset held by the Gazan enemy.

I said to the terrorists: Maybe it's better to be down in the tunnel / Sapir Cohen

After a long walk, during which I stepped with my bare feet on nails and other unfamiliar objects, I was brought to a place that looked like a shelter, with concrete and thick walls, and I was ordered to enter the elevator. The "elevator" was a concrete block that somehow moved vertically. I didn't know I was in a tunnel because I entered straight into a space with porcelain paving, but I quickly learned that there are "tunnels" and there are "passages between the tunnels", through which one can cross from one space to another. A "passage" is, for example, the narrow tunnel where the bodies of the six murdered hostages were found at the end of August. These are the narrow, low, and arched passageways that Israelis know from the pictures.

After spending a few days in an underground tunnel, I climbed up using a ladder, and I was moved through the passages to houses located above the ground. All the houses I was held in were connected by tunnels. When I stayed in the houses I would hear terrible bombings and thought it would be better to be down, inside the tunnel; but when I told this to the terrorists, their answer was: "No. If there is a bombing you will suffocate down there." Still, after a short while, I returned to the underground tunnel.

Inside the tunnel, there is no light at all. Sometimes a terrorist would turn on a flashlight, but still, I could see nothing. There is no air either. One of the terrorists had an oxygen cylinder; there was this time when I had trouble breathing so he let me use it. However, when in the tunnel no one can hear you, so you can speak loudly, unless it annoys the terrorist.

There were some tunnels with electrical infrastructure, which sometimes worked and sometimes didn't. The senior terrorist who was guarding my group had some knowledge of electricity, so now and then he would fix it. Sometimes there were batteries available, and I also saw generators there, but it didn't help us.

The tunnels are damp, and you constantly have to wipe the water that drips from the ceiling onto the walls and floor. The five thin mattresses we slept on were also soaked. The humidity caused mold, and the smell was so terrible that it was impossible to fall asleep. When I went from the houses back to the tunnel I took a Q-tip I found there, and a day later it turned green. People developed skin diseases, and wounds started appearing on their bodies. They scratched because there were lice and fleas, and you couldn't shower. We looked pale, with dark circles under the eyes.

In the tunnel, there is nothing to do besides talking to the other hostages. Also, there is no sense of time. At first, I had no idea when it was morning or night because everything looked the same. But the terrorists prayed five times a day, so I was able to tell, roughly, what part of the day it was.

The main food you get is pita bread. When there were no pitas, we would eat nothing. Since every tunnel with hostages is located adjacent to a house, one of the terrorists would climb the ladder, take food, and bring it down. There was this time when the house near us was bombed and the children there were seriously injured by shrapnel, so whoever lived there did not allow providing us with any food at all.

There was a small refrigerator in the tunnel, but of course, it didn't work. There was also a tap with salted water, and it didn't always work either; so, if the terrorists didn't provide us water - we wouldn't drink. We tried to save food, but the pita would get dry and moldy after a day. Our tunnel had a gas unit, and when it had gas in it, we would heat the pita so it would be easier to bite.

We would try to find ways to take food without the terrorists noticing, to hide it and remove the mold from it. The terrorists held daily "meetings", they would go into a nearby room, so we managed to take pitas and hide them. Still, there were days when there was no light, no electricity, no gas, no water, and no food.

We were lucky to have toilets in our tunnel, which was unusual because other groups of hostages didn't have any at all, or they had ones that wouldn't flush. I know that this was the case in the tunnel where they held the elders. There was no medical treatment either. There was a hostage with me whose leg was injured and swollen, and he was limping. There was nothing we could do about it.

The tunnels in Gaza are so ramified that even terrorists had trouble finding their way around. You need to have someone who knows it well and can tell where to go and which turn to take. I heard from other hostages that they had to walk underground for hours because the terrorists who held them didn't know how and where to go.

Each group of hostages had several terrorists who served as guards. Some terrorists carried their weapons in public and some hid their weapons. Now and then we would hear a weapon being cocked, which is petrifying. We were mostly afraid that Israeli soldiers would try to rescue us because we knew that in this case, the terrorists would shoot at us.

All this time I knew I was underground in Gaza and was surrounded by terrorists, but I didn't internalize it. For a certain period, I lived in another world, disconnected, as if something happened to my body. But things change. I met hostages who didn't know what happened to their families, or those whose family members were murdered in front of their eyes, and I felt the need to put my problems aside and help them. I said to myself that no matter what, I would do everything in my power to help, bring them food, and talk to them. That's what kept me going. This has become my life's mission.

Sapir Cohen, 30,was abducted on October 7 from her partner's house, Alex (Sasha) Trufanov, in Kibbutz Nir Oz. She was released with his mother Yelena and his grandmother Irena Tati in the final swap deal after spending 55 days in captivity. Her partner Trufanov is still in captivity.

Other armies are already learning from us / Prof. Kobi Michael

In the Iron Swords War, the IDF was exposed to a different reality in Gaza from the one it once knew, or thought it knew, because IDF's last maneuver in the field occurred a decade earlier, in Operation 'Protective Edge'.

They knew that Gaza was networked with tunnels, but never imagined they would discover tunnels in such dimensions in terms of their scope, depth, system, and sophistication, including the connecting points between the various tunnels. They did not know that the underground network allowed Hamas terrorists to enter the tunnel in the Philadelphi corridor and end up above the ground in the northern part of the Gaza Strip. They did not realize that hostages could stay inside for a long period and did not know that they were connected to civilian infrastructures such as hospitals. The professional building of the tunnel network indicates that they used external help and expertise.

The IDF needed quite a long learning time to deal with the tunnels that were gradually unfolding, since entering the tunnels is complex to begin with – usually via hidden, narrow, and sometimes very deep shafts.

But over time they managed to deal with it, and could also tell the difference between tactical tunnels that were used for combat and attacks, and strategic tunnels that included equipped and advanced command and control rooms, which supported the tactical tunnels and were essential for Hamas activity.

The next challenge the IDF had to face was how to destroy the tunnels. After various strategies were examined, such as flooding, which was proved unsuccessful, other methods were developed, apart from the use of explosives. The IDF continues to this day to uncover the underground infrastructure, but it is complex due to the enormous number of tunnels and their ramified structure. Moreover, the tunnels must first be discovered.

The tunnel in Rafah where the bodies of the six hostages were found at the end of August, was unfolded almost by accident since its shaft was hidden inside a children's room in a residential building. Imagine how many more shafts are out there, especially in densely populated or ruined areas.

However, the IDF has already learned about the close connection between the civilian infrastructure, the population, and the tunnels. Not only do they know that Gaza citizens participate in the digging, but they know also about the critical importance that Hamas attaches to the symbiosis between life above and below the ground: there may be a shaft in every school and a tunnel under every hospital. The connection between the upper construction and the lower construction adds to the complexity.

As a result, the IDF has developed a new theory for underground warfare. There is no other army in the world that faces such a threat at such a level. And apparently, this is not over yet. Until the IDF leaves the Gaza Strip - if they ever will - they will continue to learn, improve, and develop capabilities and new fighting methods. Other armies worldwide are already learning from the IDF.

The bad news is that Hamas tunnels are not an unusual phenomenon among our enemies. We discovered the giant tunnels penetrating from Lebanon already in 2018, and only recently, underground routes - albeit short ones - were located in Tulkarm and Jenin as well. This will have consequences on the IDF's forces, which will require more engineering forces, expanding units such as the Yahalom (Special Operations Engineering Unit), and investing in the development of combat measures and methods.

Prof. Kobi Michael is a senior researcher at INSS and Misgav Institute

I crawled between the crumbling walls / Staff Sergeant D.

During the war I did everything in the tunnels - I scanned, destroyed, ran into combats, and even rescued bodies of hostages. On the one hand, fighting underground involves a greater risk, because if something happens you are in trouble: it is complex to get assistance from the outside, and the only ones who can help you are your comrades who are with you. On the other hand, it is a relatively quiet place, and if we reach it, it means that the odds of encountering the enemy there are not high.

It wasn't discussed much in Israel, but some fighting in the tunnels of the Gaza Strip took place already a decade ago, in Operation 'Protective Edge'. Based on this experience, among other things, we trained for underground activity long before the 'Iron Swords' war began. Did we know what we were getting ourselves into? We didn't expect everything we saw there this time, but the truth is, there was nothing we encountered that we couldn't handle.

Before entering the tunnels, there is excitement among the soldiers. I cannot define it as "fear", but we feel we were trained for a unique mission and know that we are ready for it despite the dangers involved. Besides, we had time to prepare ourselves mentally, because, in the beginning, we were mostly busy destroying the tunnels that were found. It took a while until we engaged in rescuing and encountering terrorists.

Before we enter the tunnels there is a preparation phase. We use technologies and intelligence to understand what is happening down there. Sometimes we know in advance where the rooms of senior officials are located. But still, we enter with caution. The danger is always there. You can always miss a booby trap or confront an ambush at any given moment.

I can't remember how many tunnels I entered, but there were lots of them. The sense of danger hovers above you all the time. You feel the sand falling on you, and you see that the walls are shaking. Most tunnels are about 27 inches wide and 5.6 feet high. I have also seen lower ones or ones that are crumbling. Sometimes I would find myself crawling between half-ruined walls that had collapsed inward. On the other hand, there are also large tunnels with rooms, showers, and running water. Once we were surprised to discover a tunnel that had nice toilets, air conditioning, and lots of water. They didn't build it for a week's stay but planned it for years ahead.

In the other tunnels the oxygen level is reasonable, and we were able to breathe during the activity, but it is impossible to stay there for a long time. They have mold, gases, and dust. We monitor the air quality when we are inside, and if the oxygen level is too low - we plan.

In most tunnels, we don't expect to find hostages alive. We focus on scanning and task completion. But as mentioned, there were cases when we entered and found bodies. Some were in such bad shape that we didn't recognize they were corpses. Once, at a depth of 82 feet, we found corpses in an advanced state of decay inside white sacks. The sight of it doesn’t leave you, especially when it's the first time you have to handle it, but today we are trained.

The only difference is the fighting inside a tunnel as compared to fighting outdoors, where you can see at a distance what's ahead of you and sometimes take cover. In the tunnel everything is limited. The terrorists can suddenly surface and strike. Therefore, the fighters who stand first in line know that they are at the greatest risk. If something happens - they get hit first.

We mainly engaged in destroying tunnels, one tunnel after the other, either by using explosives that we placed manually, or by airstrikes. But beforehand we do everything in our power to make sure there are no hostages inside; this can take days and thus delay the operation, but there is no other choice. The fear that there might be Israelis inside never leaves you.

We still ask ourselves if our operations destroy the tunnels completely or if Hamas can come after we're done, clear some rubble, and reuse them. As far as I can judge, considering my activity since the beginning of the war, we neutralize them completely. Whoever wishes to reuse these tunnels will have to dig and rebuild them. Yes, we discovered an elaborate underground tunnel network in the Gaza Strip, certainly more complex than we expected, but I think we can destroy it all. It's only a matter of time.

Staff Sergeant D. is a fighter in an elite unit.

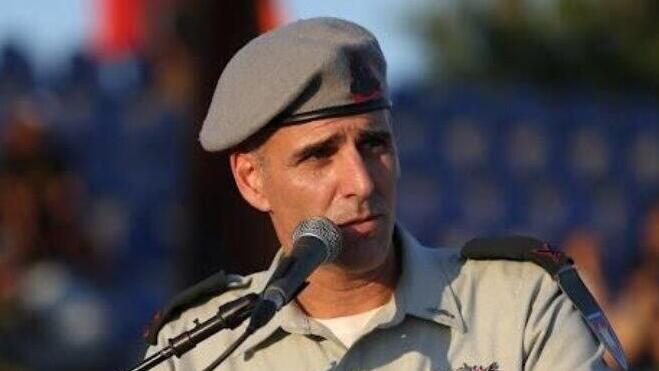

Like running up a descending escalator / Brigadier General (res.) Ido Mizrahi

Hamas is a sub-state terrorist organization that uses the underground to store its military and other assets. This is their only way to offset the absolute advantages of Israel and the IDF. As much as Israel enhanced its capabilities in technology and the air force - Hamas deepened its capabilities underground and expanded the "underground infrastructure". I use this term because it is important to clarify: These are not just tunnels. Many of the important assets and means of Hamas – military headquarters, production workshops, and storehouses - are underground.

Handling this subterranean complex requires a continuous learning effort. It is equivalent to running up a descending escalator: you can't stand still. As you level up, the enemy also makes its next move - deeper and more hidden. In the Iron Swords war, we learned how wide and deep this underground network of Hamas is really like.

At this stage we have very good control in the field - one should never say "absolute" - and we use it for learning. This is one of the most beautiful processes I've seen until I finished serving as Commander of the military's Combat Engineering Corp in January 2024; since then I have continued watching it from the outside: a military unit encounters a certain challenge, deals with it, learns lessons from it, the knowledge is passed on to the neighboring units, then to the entire military and civilian system, and then relevant solutions are offered to handle the problem. Sometimes it involves the top of technology and sometimes it uses medieval low-tech.

Since the main characteristic of the underground network in Gaza is concealment, it is very difficult to know what is under our feet; therefore, a great effort is invested in gathering intelligence, and technology and in locating and mapping the tunnels, long before the neutralization stage occurs.

To neutralize the tunnels, we tried almost every possible solution, be it technological or other, and every idea that came up was granted legal approval by international law. One of the solutions, which was also published in the media, was the "Atlantis" project, in which we channeled seawater into the tunnels. But the ground in the strip is too sandy and a large part of the water seeped through it. To make it work, you needed a substance that could move and not be absorbed. I will not go into details about how long we tried it and to what extent it eventually helped us.

Fighting underground requires unique training. It is not suitable for every soldier. As in many fields in the IDF, here too there is a wide range of skills. That is: some units have undergone a few weeks of basic training in underground warfare, and there are units such as Yahalom (Special Operations Engineering Unit), whose soldiers train for months for tunnel warfare. The training is carried out in special training facilities that simulate an underground infrastructure.

In the field, one of the most significant challenges in underground warfare is that once you send a force into the tunnel, it is very difficult to communicate and know what's happening. Fortunately, we are the army of the "Startup Nation", and after presenting this problem to the defense industry, they came up with a solution, in an impressively short time. This is not a case of "fire and forget". Still, this is a very risky fighting, compared to a classic ground operation, but everyone who enters the tunnel is provided with communication devices that enable them to portray a situational picture and also keep the troops safe.

We are still using all the knowledge we have accumulated until October 7, 2023, but there have been developments and changes in tactics since then. Every team that has operated underground since then has learned lessons of do's and don'ts. Some of them are tactical, and some are at a higher level, which requires building a new capability, a new technology, to gather new intelligence on a scenario we haven't encountered before. Learning lessons during a war is not obvious. The IDF does it impressively.

Brigadier General (res.) Ido Mizrahi is the former Commander of IDF Combat Engineering Corp.

No one can tell if the damages caused by the tunnels are reversible / Prof. Silvana Fennig.

Many of the returned hostages that were treated by us spent most of their captivity time in houses of families, and they went underground only when bombings were taking place. The time spent in the tunnels must have been terrible for them, partly due to a lack of stimuli and light. The sense of claustrophobia and the lack of air make it difficult not only physically but mainly psychologically. The long-term damages are also mainly mental.

Despite the deficiencies and the weight loss, the children did not experience anything physical that might be irreversible, however, the psychological damage is not always reversible. I cannot tell what the future holds for them, but generally speaking, children who suffer post-traumatic stress disorder might experience anxiety and depression even years later. The terrible fear of death may affect one's personality fundamentally.

They suffer a complex trauma because they were taken to captivity after experiencing a previous trauma. They were hiding for hours in terrible fear, and after they were pulled out of their hiding place they witnessed murder and horrible sights; with these images in mind, they were taken to Gaza. Everything adds up.

Their coping depends on how they spend their time in captivity. If they were with a family there, then the situation is completely different than being alone. The children who were there with their parents experienced a certain sense of security, and this is also true for the adults who went through it along with someone close. This is very helpful for survival; we know it for a fact from both research on the Holocaust and the experience of Yom Kippur War captive soldiers.

When the hostages returned, after the celebration and all the excitement around them, they returned to a shattered community, as evacuees, without a home. The gap between the collective joy of millions of Israelis and their individual story is not simple. They continue their life routine while they are no longer in the news headlines, and they are no longer the heroes. We took this into account when we decided to reduce stimuli - including limiting the number of visitors, even the happy ones - because transitions are not easy.

We usually operate by evidence-based study rules and techniques with worldwide supporting scientific evidence, but there are no guidelines available for treating children who returned from captivity during a war because it is extremely rare. We knew that we would have to 'learn on the go'. Professionals base their treatment on past studies and professional literature, and here we had nothing to base our work on.

In total we received 26 people, 19 of them were children. We built an inpatient care ward for both young and adults, away from the media, to reduce damage. It was a quiet, sterile, and remote area, with as little stimulation and noise as possible. We had to act at their pace, follow them step by step, respect their routines and rituals, and hear and listen, without pre-built formulas.

Beyond the obvious physical medical needs, it was important, psychologically speaking, that they return to a place that can provide professional help. But we knew that our help was only temporary. We were debating whether it was right to bring them back home directly from captivity. Unfortunately, most of them didn't have a home to return to, anyway. They were evacuated from their homes.

Prof. Silvana Fennig is a pediatric psychiatrist and Director of the Department of Psychological Medicine at Schneider Children’s Medical Center.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: