Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

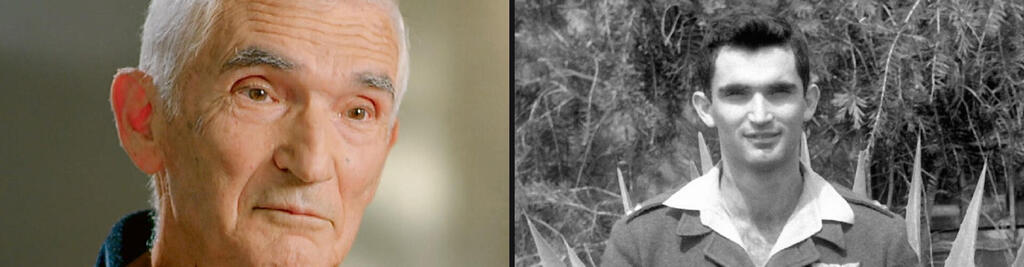

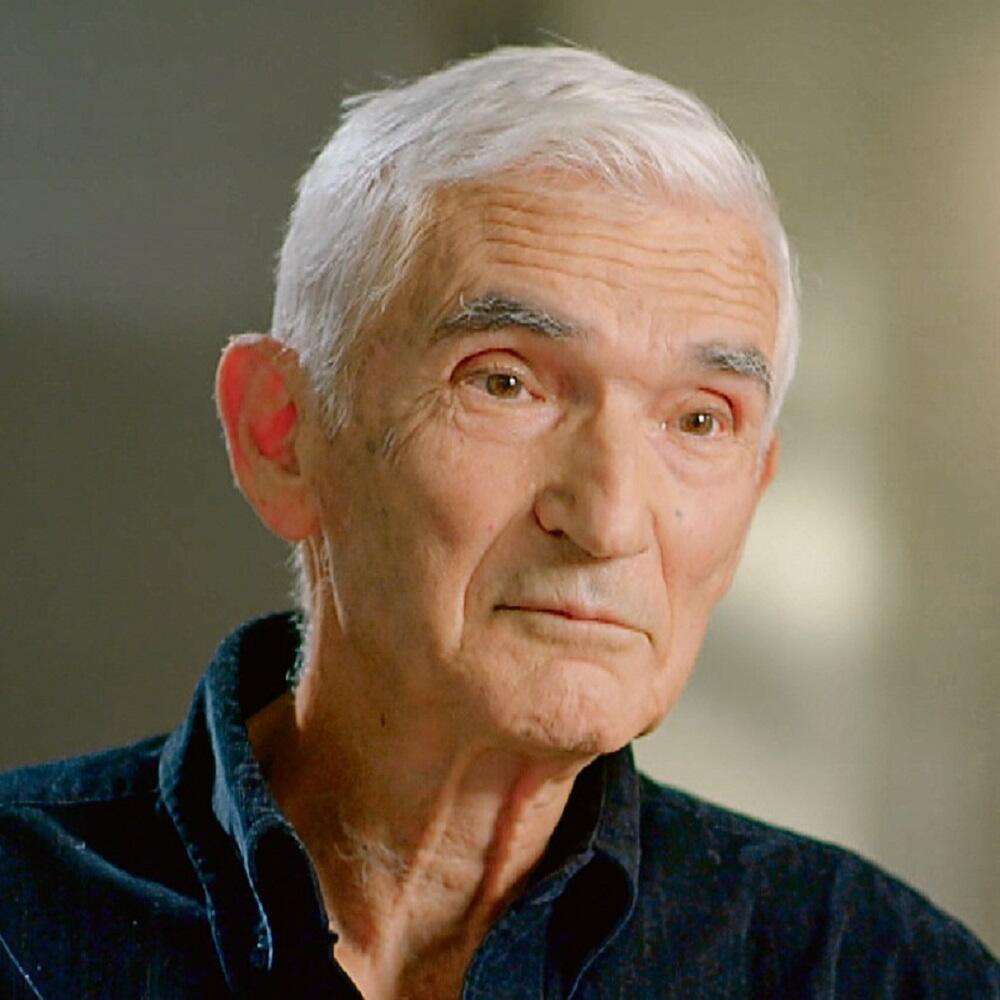

"For 50 years, I haven't talked about this thing. Until today. 50 years," an elderly man, in his ninth decade of life, steps onto a small stage in the heart of the hall. In the audience sit several dozen people, among them his wife, children and grandchildren, who have come to a conference of the Israeli Association for Military History held a few months ago. It is precisely there that he chooses to speak openly for the first time about his involvement in one of the most traumatic events in the history of the Air Force and Israel as a whole.

Read more:

"For many years, security services advised me to keep a low profile," he continues. "The only person I confided in was my wife, who has known since day one. While serving as a pilot for El Al, I faced numerous restrictions and flew under an assumed name due to intelligence warnings about potential kidnapping threats.

“Over time, specific intelligence indicated that terrorist cells had acquired information about me, obtained during the Yom Kippur War. We had several prisoners in both Egypt and Syria captured who were subsequently tortured to extract information about my identity. After the war, one of these prisoners told me, 'Faced with escalating electrical torture, I disclosed your name.' My response was, 'I hold no grudge against you. I've never experienced such torment or anything remotely like it. I'm in no position to judge you, nor do I harbor any negative feelings toward you’."

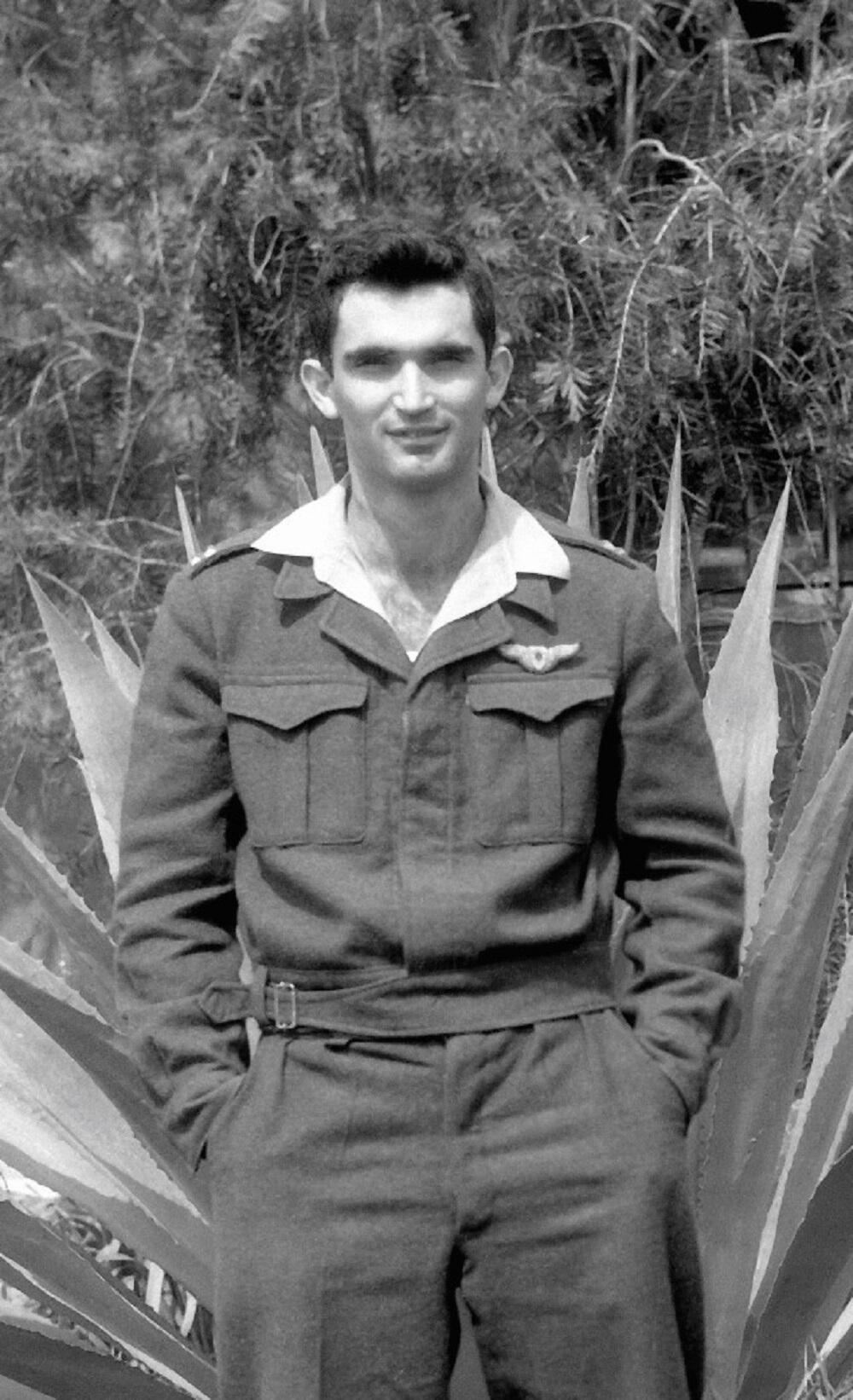

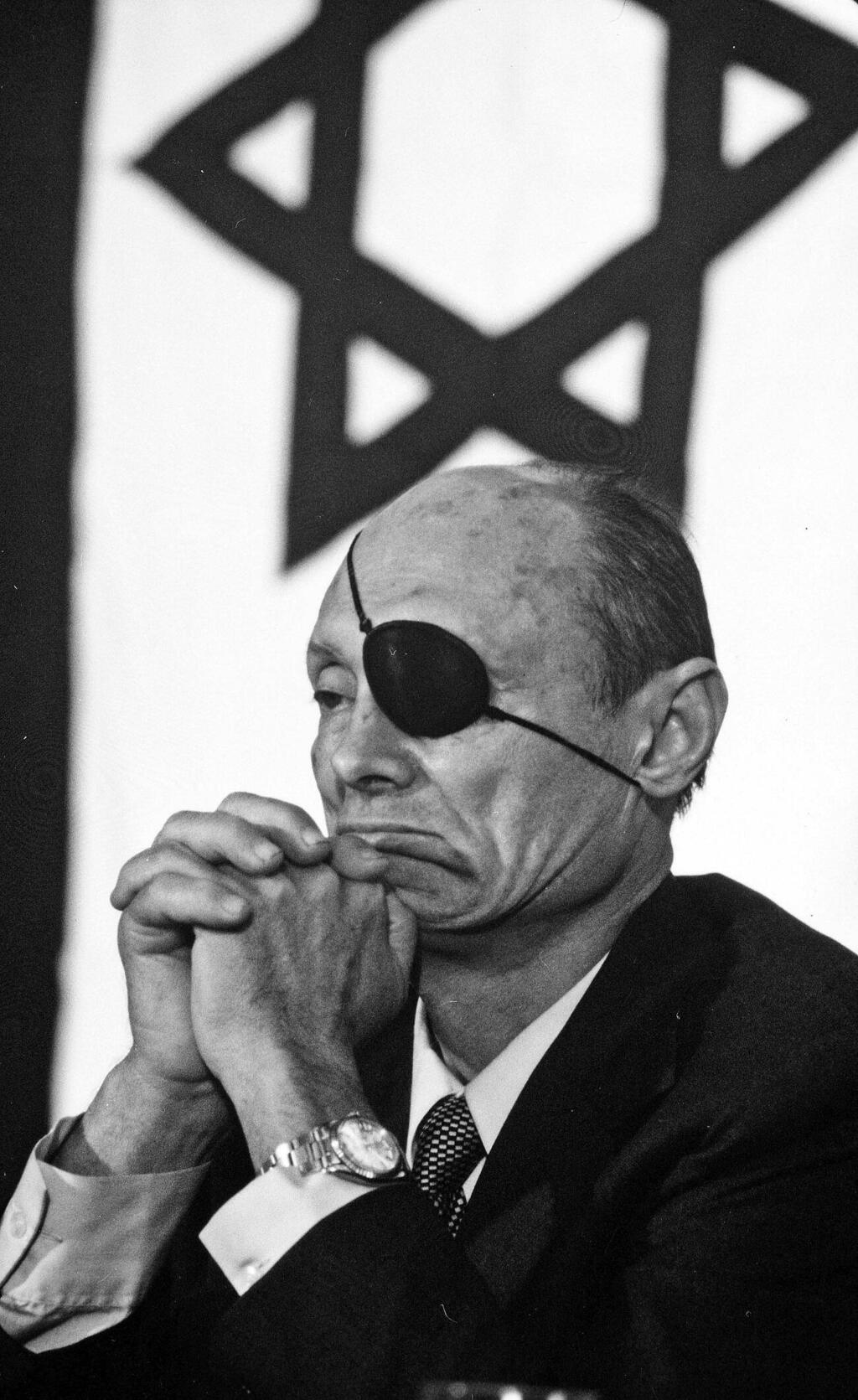

In 1973, Lt. Col. Yiftach Zemer served as the commander of the 201st Phantom Squadron, known as The One, considered the spearhead of the Air Force. On February 21, 1973, due to a series of coincidences, a chain of mistakes and bad luck, Zemer and another pilot shot down a civilian aircraft from Libya.

At that conference, for the first time in 50 years, he publicly said six words: "I shot down the Libyan plane." Even his eldest son, age 53, heard for the first time his father's extraordinary story.

A command called 'Nightmare'

A heavy fog prevailed at 12:40 in the afternoon on a Wednesday, when a Boeing 727 that took off from Benghazi in Libya to Cairo, the capital of Egypt, lost its way and accidentally entered Israeli airspace.

Two Air Force Phantom jets were scrambled toward it, trying to divert it, fearing it intended to strike a strategic target like the Dimona reactor. Due to the extreme weather conditions, the pilots struggled to identify the passengers on the civilian aircraft, as all its windows were fogged up. They signaled twice to the Boeing pilot and fired warning shots near him, but to no avail.

11 View gallery

Yedioth Ahronoth front page; February 22, 1973; Co-pilot of Libyan plane: 'We saw the Israeli planes, but decided to flee due to regional tensions'

Then, Air Force Commander Major General Moti Hod gave the fateful and controversial command: "Shoot it down!" 108 innocent civilians were killed. Five were seriously injured but survived.

The disaster made headlines in Israel and around the world, but only now, 50 years later, are unpublished details about the tragedy being revealed. In the new documentary series The One by Yedioth Ahronoth journalist Sima Kadmon, marking the 50th anniversary of the Yom Kippur War, the chilling monologue delivered by Zemer is presented here for the first time. In it, he describes the dramatic chain of events that shook his world and scarred his soul for the rest of his life. The series is airing these days on public broadcaster Kan11.

"On February 21, '73, a wind blew that I had never seen before," Zemer recalled. "A terrible sandstorm, in the middle of day. Suddenly, a siren sounded. We were on standby at the Refidim base, the planes were 50-60 meters in front of us. When we ran frantically to the planes, we couldn't see anything.

“We are the men of the 201st, Phantom planes, and of course, each plane has a pilot and a navigator. There are four of us. The controller says to me, 'A plane has penetrated the Suez Canal airspace.' I ask him, what's the situation at the airports? He checks and says, 'All the fields in the center of the country are red, closed.' And what about the fields in Sinai? He tells me, 'Sharim is open.' Great, so in case we take off, whatever the weather, there will be somewhere to land."

“There was a crosswind, wild in a way that wasn't expected. I said to Doron, my number two (the other Phantom pilot): 'Take off close to me, five seconds after me.' And that's how we took off. We ascended to an altitude of around 7,000-8,000 feet. In these conditions of wind and dust, visibility at low altitude is disastrous, but as you climb, it improves. Not good visibility, but reasonable visibility.

“First thing, I tell my navigator to keep an eye out. Since we knew the terrain well, I knew the heights of the hills in the area. I told him to make sure we don't go below 3,000 feet, as that's dangerous and we could collide with the mountain peaks.

“Very quickly, I see on the radar the suspected aircraft flying north, and I slowly approach it, matching its speed. It's flying slowly by our standards. Throughout this event, by the way, we're both at the same speed, 250 knots (about 460 km/h). I'm flying behind him, 100-200 meters, it's hard to say. I see a fuselage and two engines on either side. I don't see the third engine in the tail. It looks like a Boeing 727 to me. I get alongside one side of it, everything is in Arabic, then I move to the other side and everything is in English.

"Here begins a series of instructions I receive, sometimes confusing, to persuade him to land. Fortunately, about six months earlier, the Air Force had established commands for what to do with a hijacked passenger plane. Usually, it would be a hijacked plane, right? A passenger plane that comes over a country, drops ordinance or crashes into it. I spent about two weeks with the Air Force commander, learned what I could about the instructions, and wrote the command. They told me the computer picks the names, but by chance, this command was called 'Nightmare.'

"My good luck, in this sense, was that I knew the signals. I begin to signal to him to land. Basically telling him, follow me for landing. You go close to him, very close, in front of him so he can see you, lower the landing gear, give a few nods—all under the assumption that you don't have radio contact with him, which was the case—wave, and start a shallow turn. In the command, I wrote that in passenger planes they turn up to 30 degrees of bank, no more.

"The plane continues in the same direction and doesn't follow me. At this point, when we are in the area of 3,000 feet, we see the ground unclearly. I didn't know where I was, because there are dunes and hills, and I try to signal to him to land for the second time."

"We're heading north, and he starts a turn left-westward. I'm on his right side, close to him, and my goal is to signal the pilot to descend, with hand signals. Then he aligns westward on the road (toward Tasa and Ismailia), as if he planned it. And I signal to the pilot like this (pointing down), and the pilot does this to me (pointing straight), like that two or three times. And again I move in front of him, landing gear, waving, follow me, nothing.

"What to do? I go in a third time, saying, now I'll get even closer. I pass in front of the wing and sit on it as close as you can before colliding with the pilot. And we see each other. We didn't see the passengers; I don't know if it's because of the curtains.

A worrying gut feeling

At 13:52, the time he was supposed to land in Cairo, as later emerged from the black box recordings, the three cockpit crew members of the Libyan Boeing tried to identify where they were, wondering if something was wrong with the instruments. “It's ticking terribly,” said the flight engineer. A minute or two later, the Cairo air traffic controller came on the communication network: “Approach Runway 23,” he told him, and a moment later added, stunned, “Your location is missing, your location is missing."

In the meantime, Zemer is trying his best to avoid carrying out the dreaded order, which he was part of drafting. “All of this is happening in the afternoon. I fly once on the right side of the plane, and once on the left, switching sides. I get in close, a centimeter, so that he's constantly looking at me, and I fire two or three bursts from the gun—not at him, but straight ahead. I'm firing bullets. You can see the bullets. I saw that you could see them even in the cockpit, even in this haze. You can see the bullets glowing. There were different colors. It was very clear.

"Later on, when there was a commission of inquiry by the International Pilots' Association, I received all his recordings. He's screaming at the controller in Cairo, 'The MiGs are firing at me, get them off me. The MiGs are firing at me.' And then there's the voice of the Libyan co-pilot. He apparently understood; he's also the only member of the crew who survived."

"In short, I'm firing, and once or twice they tell me on the radio, 'Shoot him down, shoot him down.' And I say, wait. The controller from 511 (the aerial control unit in Umm Hashiba) is speaking with me. He is on the phone with the Air Force Command Center, which is giving him instructions to pass on to me. So, I hear him say 'Shoot him down' one of the times when I'm circling around the plane.

"The second time he tells me, 'This is an order from the Air Force commander.' There's a code word for the Air Force commander that all pilots know. The same term is used to this day when the commander gives the order to shoot down. And I say, 'Wait a moment. Wait. Wait, wait.' I have a gut feeling that I can't explain, that this is a mistake, it’s one big misunderstanding.

"The navigator starts to pressure me, and rightly so; it's his job to do that: We’ve got to be done with it immediately and return because we are already halfway (between Refidim and Ismailia), and that's where the enemy is located.

“There was an alert system on our planes that could detect and display the 2-SA missile, a huge electric pole with a long engine that could fly up to 70,000 feet. Its launching station includes a ground radar that scans the entire sector. We have the ability to know when the radar is active. When this radar spots an enemy craft, it locks onto it and stays locked. It was already locked onto us, and the navigator started to shout at me. The most serious situation is when the radar begins transmitting firing instructions. Our alert system had already told us: there are firing instructions. That's our situation. We have no additional warning if the missile is really in the air."

"Now, the visibility is terrible. The missile is coming from the west directly toward us. We are flying westward; the missile is flying eastward. This means we only see its width. The flame is behind it. There's a chance we might have seen the flame from behind—against the background of the horizon, it would be more visible, perhaps—but I didn't think about that at all.

"Throughout this stage, from the moment the plane first didn't respond to my command until the first time the order 'shoot it down' was given, I'm oscillating between flying the plane and telling the second-in-command what to do, all the while thinking, 'Is it a black flag or not a black flag? Blatantly illegal or not blatantly illegal?'"

"I shoot because I'm a man of the system and I follow orders, even if I don't like them. I do whatwever the Air Force commander tells me"

“Without a doubt, this is a direct order from the Air Force commander. Someone who has the authority to do so. He is in the bunker; he has sources of information that I don't have. I don't know what this plane is. When I caught it, it was between Umm Hashiba and Bir Gifgafa (Refidim). From my experience, when I wrote the order half a year earlier, Umm Hashiba is a very important target. There are others too—Dimona's reactor, of course, Tel Aviv. They are less relevant in this case, but Umm Hashiba could definitely be a target. And I don't know what the plane is doing, where it's going, and I'm constantly busy wondering whether my own judgment is strong enough to override an order from the Air Force commander.

"In the end, you have to decide. It was clear to me that if we continued, the missiles would take us down. At a speed of 250 knots, my maneuverability is terrible; there's a good chance the missile will take me down."

"A brief consultation with the navigator. The navigator says go home immediately. I decide to do one last thing. Try one more time. I don't even know how many things I've transmitted and how much I've shouted out of anger and excitement like, 'Guys, what do you want from him? He's lost.' That's what I'm thinking in my heart. I'm not shouting that out. And I say, last attempt. He doesn't respond. Nothing. And then I shoot.

"I shoot because I'm a man of the system and I follow orders, even if I don't like them. I do whatever the Air Force commander tells me. I aim for the rear part of the plane, where the engines are located. I really hoped he would manage to make a forced landing on the dunes.

"I fire two short bursts and wait to see what happens, and I see that he starts to descend. I start to see smoke coming from the rear part. I realize that I've hit and I follow it. It lands close to the road. It has people, I know; from the grandstand, I saw it. There were a few dunes, the plane bounces, descends, bounces again, almost flips, it doesn't completely flip, it tumbles.

"I remember it from time to time, usually at night. There are two points that I see in my eyes. One of them is that this plane hits the ground, gets tangled up, dust rises and smoke comes out. And then you see plumes of black smoke like that, and it's clear that it's probably fire. I have nothing more to do there, and I return. We land. How? I don't know. When I took off, I was sure I would return to Sharm El Sheikh, but we landed at the base in Refidim. The Air Force commander catches me on the phone. 'Run immediately to the hospital. That's where they are bringing the survivors. Run and get their signature, because it's...'

11 View gallery

Yedioth Ahronoth front page; February 27, 1973; Dayan: 'I am sorry for the Arabs who were killed, no less than if they were my own people'

"The pilots wanted to come with me. I told them, 'You're not coming, you're staying on standby.' That was an excuse. I'm so glad they didn't come with me, because it was a harsh sight. What can you do - we pilots have the privilege to not see those we hurt with our own eyes.

“There were harrowing screams. The stench of flesh... burned people. A terrifying stench. Almost no one could be talked to. I could speak to the Libyan co-pilot, but he was in shock. He mainly spoke French. He didn't answer me, and it suddenly dawned on me that I wouldn't be getting any signature from him. The hospital is the second thing I sometimes remember at nights, besides the plane crashing into the dunes. The screams, the smell of burned people. It's been haunting me for 50 years."

Here are the keys to the squadron

Two days later, both pilots were also dragged to the press conference. It turned out that the order was given by then-Air Force Commander Major General Mordechai Hod after updating Chief of Staff Lieutenant General David “Dado” Elazar, and receiving his approval. Dado, who approved the order while still groggy after a night of a major operation in Lebanon - didn't know at that moment that it was a civilian passenger plane. Then-Defense Minister Moshe Dayan brushed it off as if it was just a grain of dust.

"The day after, at home, the first thing I do is pick up the phone and call (Major General) Moti (Hod), the Air Force commander, and say to him, 'Moti, look, people are coming under pressure here. We did a harsh act. We want to at least understand what's behind the decision. Can we meet you for coffee?' 'Of course.' The next morning I get a message reading, 'Tomorrow afternoon you are with the Air Force commander. An hour after that, you're with the chief of staff, and the day after that with the defense minister’."

"We head down to see Moti. In the meeting with him, I felt something in my gut that I didn't like—avoidance of responsibility. He didn't explicitly say, 'I gave the order.' Not a word on 'why I said yes.' We then go to Dado. He says, 'I came home in the afternoon, after two days without sleep and intense activity, dead tired.' Moti had called him before making the decision. 'The phone call came just as I was falling asleep, and I told him, ‘Moti, I'm so exhausted that I don't understand what you're saying to me. Make whatever decision you need to make, I'll back you.' That's what he says to him. Perfectly fine."

"And then we go to Moshe Dayan. Although the song We Both Come from the Same Village wasn't written about me and him, we do both come from the same village. He was a cohort of my parents back in Nahalal. I've known him since I was a child. Dayan said, 'Ah, hello, how are you? How's your mother?' I decided I wasn't going to play friends with him; I was going to be businesslike. I said, 'Thank you, we've come on behalf of the pilots. All of us,' I told him, 'not just me, don't understand why the decision was made the way it was, and we want to understand.'

“He started to go around in circles, and he almost repeated his slogans. Do you remember his slogans, 'Better Sharm El-Sheikh than peace,' 'Our situation has never been better'? And this was just before the Yom Kippur War. I left there in a bad mood for the entire evening."

"I don't go home, but instead to the residence of the base commander, Rafi Har-Lev, who was then at the end of his tenure. I tell him about the round of meetings with the generals, put my hand in my pocket, and say, 'Here are the keys to the squadron, take care of it. Tomorrow, have someone new in place.'

“And he says, 'I understand you, let's have a drink and calm down for a moment. The turbulent state you're in isn't suitable for making drastic decisions. I know you. You're making a mistake you'll regret. Let's make a deal. Starting from tomorrow morning, you take two weeks off. I'll arrange two El Al tickets for you and your wife. You go wherever you want, and we'll talk when you get back from your vacation.' Oddly enough, he managed to get through to me.

"We flew to London. When we returned, there was a long conversation with Rafi, and also a conversation with Benny Peled, who it had already been announced would be the new Air Force commander in place of Moti Hod. Both of them said to me, 'The Air Force needs you; we want you to stay a few more months.' We agreed that I would stay until mid-October. And in October, everything changed."

In October, the Yom Kippur War breaks out and everything does indeed change. But 40 years later, when the State Archives are opened, familiar patterns will start to emerge. One could already discern back then the arrogance, the grandiosity, the refusal to take responsibility. Israel will officially apologize and pay compensation, but Prime Minister Golda Meir, Defense Minister Dayan and Chief of Staff Dado will conclude that it was the fault of the French-Libyan pilot. Dayan and Golda will also oppose the establishment of a commission of inquiry into the greatest aviation disaster in Israeli history.

Could such an inquiry have changed the course of events? Stopped the impending calamity that was looming? We will never know.

"About five years after the event, I'm already a civilian, reading an interview with Moti Hod," Zemer summarizes. "He has retired from the military altogether, not just from the Air Force, and of course they also ask him about the Libyan plane. He doesn't dodge the question, he says, 'Yes, there was ambiguity, the weather, etc., and the squadron commander who was there on the ground decided that it was the right action to take, and he took it.' Good. We had a difficult conversation."

"The navigator of the second Phantom, Baruchi Golan, who was the youngest among us, was killed in the Yom Kippur War. Baruchi's pilot, Doron Shalev, died in a plane crash in 1977. And my navigator, who sat with me in the cockpit, works today in high-tech and is not willing to be identified or talk about it. For me too, this is the first time in 50 years that I am opening up on the subject, not just to my close ones. I often remember that event. This case is a turning point in my life."

Human and sensitive. My commander/Sima Kadmon

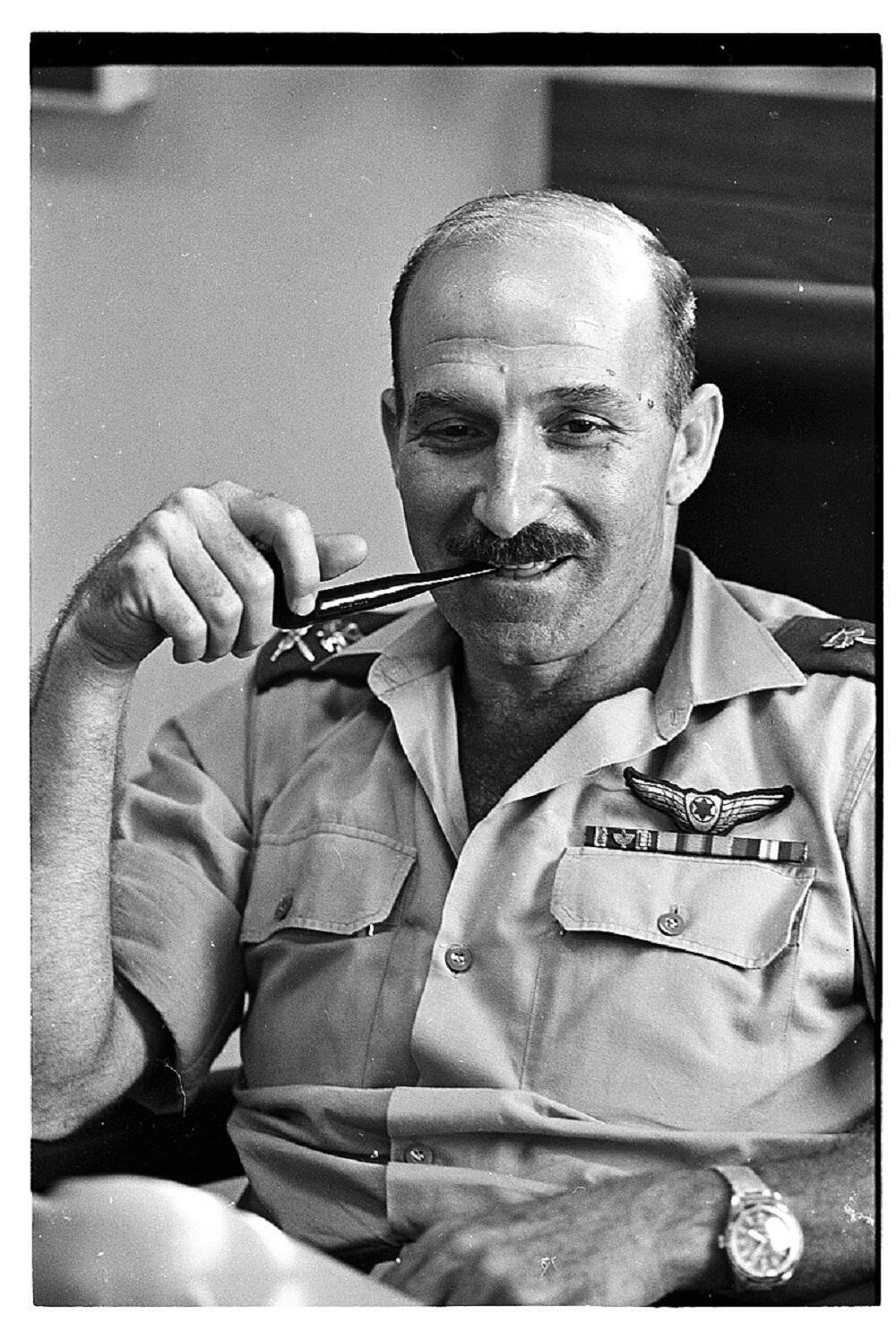

Yiftach Zemer was my squadron commander. I loved him then, in 1973, and I love him to this day. Zemer was a different kind of squadron commander. Maybe he wasn't the best pilot in the squadron, but he was humble, ethical, fair and honest. He was not considered a person to act wantonly; he hated alcohol and avoided dance parties, but he took care of people and attended to their needs.

He knew closely every soldier and officer in the technical wing and dealt with the small and personal details of all his subordinates. An operations clerk whose heart was broken, an officer who got entangled in debts, a missing soldier who needed a home visit, and of course his personal driver, Yoel, whom he nurtured with the devotion of a loving and compassionate father.

In the year before the war, I remember moments when I felt a part of a secret. A well-hidden secret. Once every few weeks, at the break of dawn, when the whole base was still asleep, Zemer would pick me up from the girls' dormitory. He would drive himself in his Carmel AFV. “Good morning Simka,” he said. That's what he called me then, and that's what he calls me today.

We would go down together to the squadron in complete silence. No plane was flying, not a living soul was wandering around the runways, in the squadrons or in the underground bunkers. An extremely unusual sight. On the flight board, Zemer's call sign was written, without any details of the operation order. Dressed in a G-suit [pressure suit], he would take off alone for a very secret flight that only the squadron commander was authorized to perform.

In the operations room, there was dead silence when Zemer was in the air. The communication channel, which always emitted constant noise and where pilot reports could be heard all day long, was closed. I sat there in complete silence until I received a message from the control tower that Zemer had landed, and a few minutes later he entered the operations room. It was clear that these flights had great significance and great responsibility. I understood that the flight was highly secretive, but I did not know what the secret was.

In the second week of the Yom Kippur War, the Mirage plane of Lt. Col. Avi Lanir, commander of the 101st Squadron, which was adjacent to our Phantom squadron at Hatzor Air Base, was shot down over Syrian territory. He parachuted safely, was captured, taken for interrogation, and underwent severe torture. He did not break during the interrogations and ultimately met his death.

Only afterward did it become clear that Lanir, like Zemer, had been trained to operate a special and secret weapon system. Then I also understood the mystery of those morning flights.

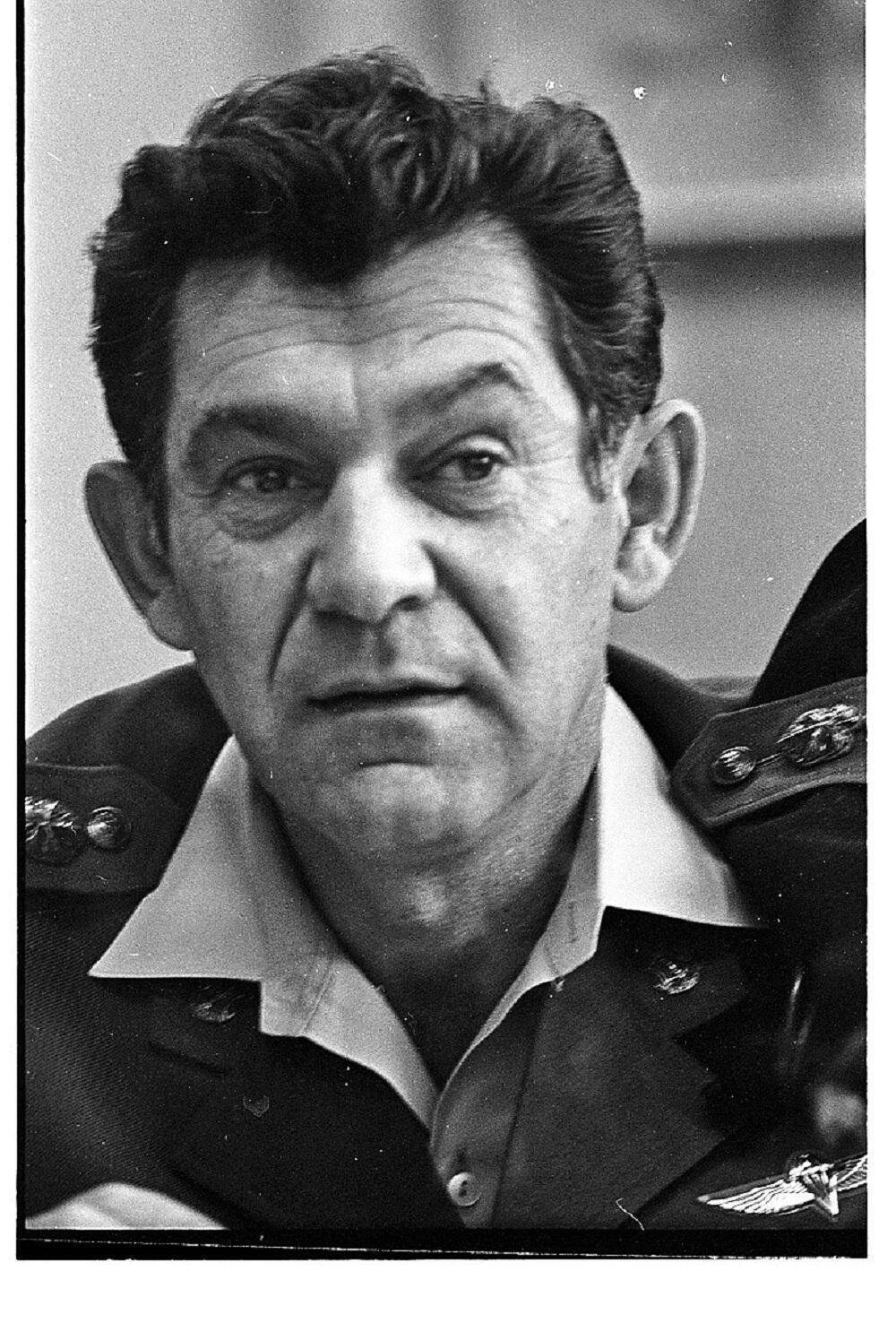

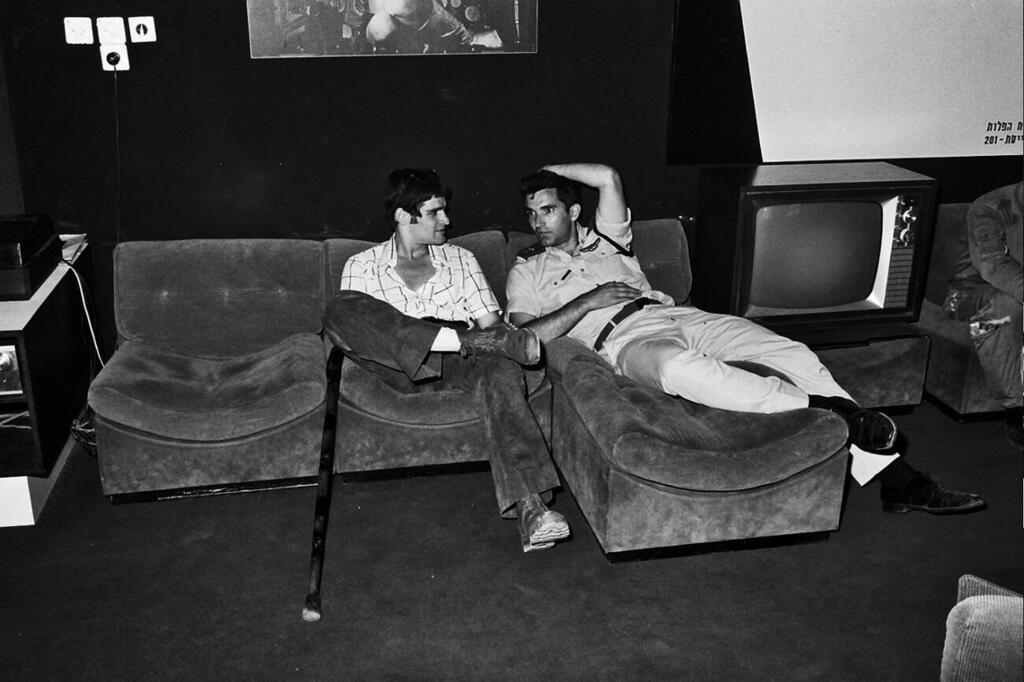

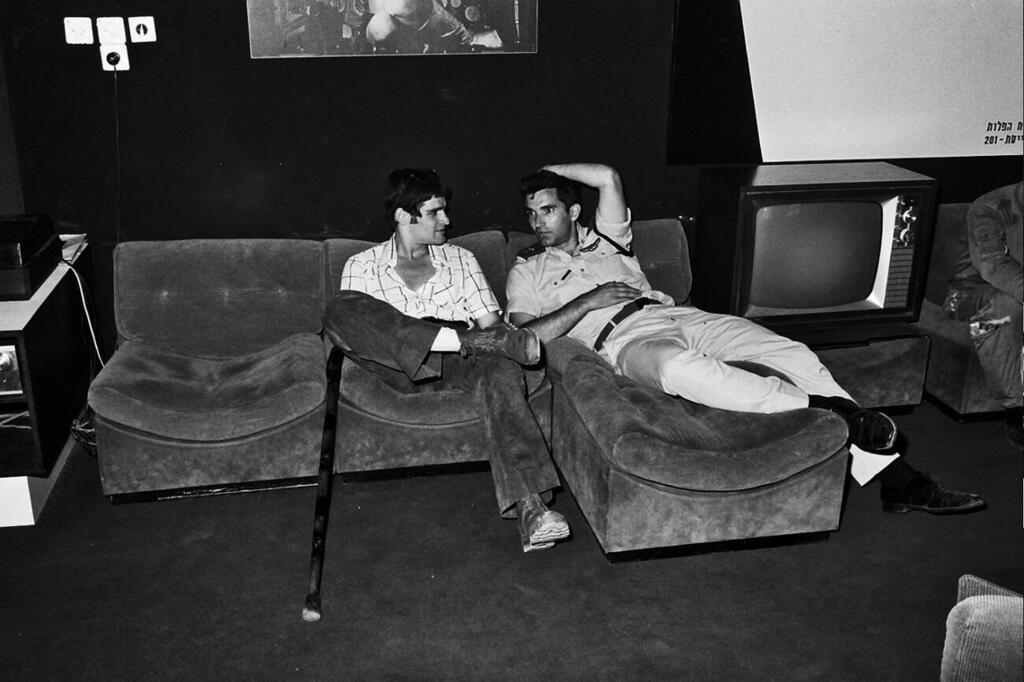

During the war, our squadron suffered blow after blow. Especially difficult was dealing with the unknown fate of pilots who had abandoned their Phantoms over enemy territory. One morning, Zemer called me and asked me to look at a picture he held in his hand and try to identify the person photographed. In the blurry image, a young man lay on a bed. The photo was taken from the foot of the bed toward his head, making it hard to identify the face. And yet, I recognized him immediately. “It’s Assa,” I said.

It turned out that Avraham Asahel, a navigator whose plane had been hit by Syrian fire, was on the missing persons list and was photographed in the hospital by the Red Cross. This was the first time he was identified, and a real chance arose that he was alive and in captivity.

That same evening, we went together to Asahel's parents' home in Petah Tikva to dispel the uncertainty. It's hard to describe the moment when parents discover for the first time that their son, considered missing, is still alive.

11 View gallery

Avraham Asahel (who fell in captivity) and Yiftah Zemer

(Photo: Hatzor Photography Department)

Yiftach Zemer visited many more times the homes of parents who had lost their children, as well as those whose children had been captured or declared missing. There were 21 such families in our squadron, and he visited all of them.

Night after night, with Yoel the driver by his side, he traveled north and south to visit the families and support them. There is no other squadron commander who did as much during the Yom Kippur War for so many bereaved families as Zemer, and it's doubtful that there was a commander as compassionate and sensitive as him.

The wounds are still open

The downing of the Libyan plane had a profound impact on the operation of the 201st Squadron during the Yom Kippur War. The effects, as well as new journalistic revelations, are exposed in The One.

The series—directed by Gilad Toktaly—chronicles the surprise, the failure, the recovery and the heroism of the Air Force in the Yom Kippur War, as never before told. It features new testimonies from pilots and navigators of the first Phantom squadron, the mythical The One squadron, all from the perspective of a young soldier who served as the squadron's operations officer—Sima Shavit (now Simha Kadmon), who has since become a senior journalist and columnist for Ynetnews’ sister publication Yedioth Ahronoth.

The 201st Phantom Squadron, known as The One, was the squadron that suffered the most losses in the war. Seven pilots and navigators were killed. Fourteen pilots and navigators fell in captivity. Fifteen of the squadron's aircraft were damaged, crashed and abandoned. Despite the heavy losses, The One took off for 758 sorties and was the Phantom squadron that managed to shoot down the most enemy aircraft in war: 35.

Fighters from The One open their hearts to Sima Kadmon and speak for the first time on camera about the crisis of command in the squadron, about conflicts that refuse to be resolved even after half a century, about pilots who feigned illness to avoid taking off for dangerous sorties, about the torture they endured in captivity and about one traumatic sortie that remains the subject of debate to this day.