Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Chapter 1: Chatting in the cockpit

On that August morning in 1973, close to dawn, "Saul" (a pseudonym) stood on the ladder leading to the cockpit of a Mirage jet. He helped the pilot strap into the ejection seat, then connected him to the internal communication system and handed him his helmet.

Read more:

Saul was the commander of one of the ground crews in Wing 4, stationed at the Hatzor Air Force Base. The pilot he was preparing for takeoff that morning was Lt. Col. Avi Lanir, the legendary commander of the 101st Squadron.

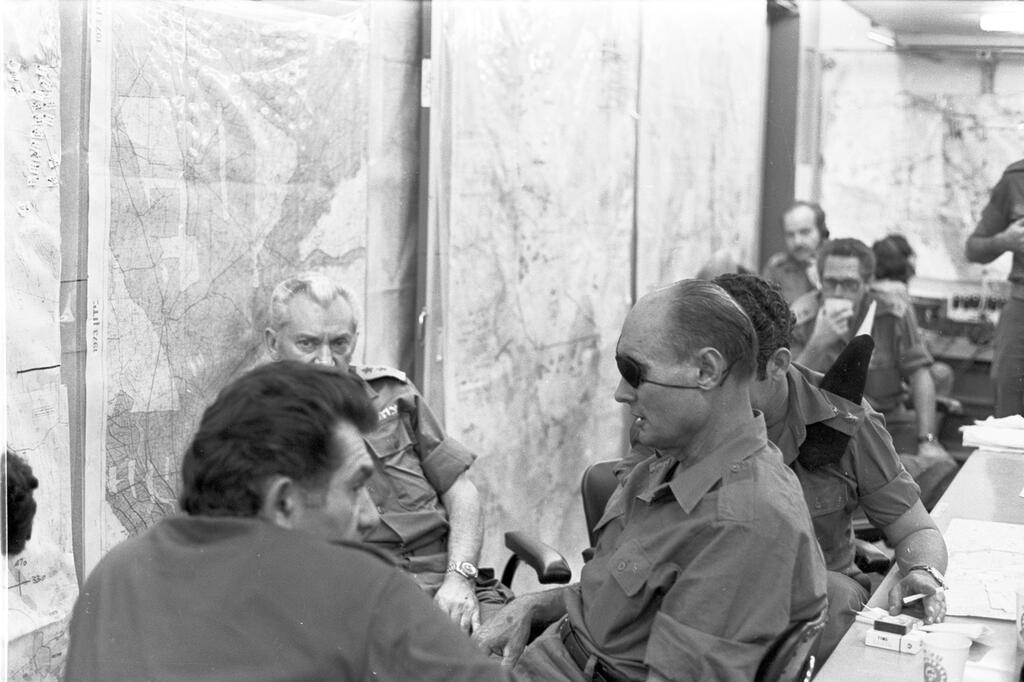

22 View gallery

Prime Minister Golda Meir, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan and former IDF chief of staff Chaim Bar-Lev

(Photo: David Rubinger)

This was no routine flight: it was a training mission involving a special weapons system, which according to foreign media reports, Israel had been developing for years and only a few people knew about.

"Even when two people share the same secret," Saul recalls that moment for the first time, "they tend not to talk to each other more than necessary. Often a secret has many details, and nobody knows exactly what the other person knows. So, it's better to keep quiet."

Saul sighs, clearly finding it difficult to speak about the legendary pilot. "But that morning," he continues, "Avi broke with his usual practice. We climbed into the cockpit. And while I was preparing him for the flight, he asked me if I knew what this was all about, and what the scenarios were for using the system."

Of course, Saul knew, and along with him, only a handful of people in the Air Force were in the know. They were there alone, surrounding the plane, inside the underground hangar (the fortified area where planes are housed on Air Force bases), accompanied only by a few individuals who were part of the highly confidential security group specifically for this system.

This security group goes beyond the usual classification given to military personnel and consists of a select few who share a specific secret. According to foreign media reports, this elite group was very small: a few pilots, one of whom was the commander of the 101st Squadron (Lanir), two reserve pilots and a limited ground crew. It was one of Israel's biggest secrets at the time.

Saul had never spoken about those days or the war that would break out two months later. It appeared he was holding back tears as he recalled that moment.

"In the late-night hours, long before Avi would arrive, we would be there to begin preparations. We would get there between 2 and 3 in the morning to ensure the plane was ready by first light. Then, close to dawn, Avi would arrive, and I'd take him for a walk around the plane so he could inspect all the systems and external installations.

"Sometimes, we would have a bit of time to kill, and we'd sit next to the plane or when he was already in the cockpit, waiting for first light, talking about all kinds of things. But only once, on that morning, did he speak with me about the training mission and asked me if I knew how such a flight could end. Of course, I knew; I was an expert in the field. So, I told him I knew, of course, and Avi nodded, as if he just wanted to make sure I understood the implications."

And why was it important for him to tell you this?

"I think he wanted to clarify to me that, if need be, he wouldn't hesitate to pay with his life."

What do you mean?

"In case of a system failure or a problem with the plane, you cannot return to base. You have one option: to fly to an open area at a remote location. Then, the pilot must make sure the plane is abandoned or the system is destroyed so that it doesn't endanger the people at the base. In such a case, the pilot might also sacrifice his life."

So why do you think he talked to you about this?

"I think he wanted to tell me, without explicitly saying it, that if the moment comes, he will not hesitate to give up his life, so long as it ensures the safety of others."

This dramatic conversation between the pilot in the cockpit and the technician standing next to him on a ladder, preparing him for a training flight that was anything but routine, replayed in Shaul's mind two months later.

It was Saturday, October 13. The Yom Kippur War had been raging for a week, and Shaul, along with some members of the 101st Squadron, was stationed at an airfield in the Sinai Peninsula, within close range of Egypt. He knew something terrible was happening.

"I saw the pilots coming back after they had to abandon their planes. I saw their eyes, I saw the distress, I saw the damaged planes. It was an extremely difficult feeling."

And then, that Saturday, Shaul heard the news: Lt. Col. Lanir's plane was shot down over Syria. The good news was that he was seen parachuting alive and walking as Syrian commando forces captured him. But then it hit Shaul: What about the secret?

"At first, it didn't dawn on me, but later in the evening, when I had a moment to myself, it suddenly connected to his question in the cockpit. I realized that at that very moment he was facing the most difficult conflict of his life: how to handle the secret he held. It was clear to me that he wouldn't talk."

So how do you relate this to his captivity?

"Because he wanted me to understand that he was prepared to sacrifice everything, even his life, if the moment came. And now, that moment had arrived on that Saturday. I was sure that he would choose to die rather than reveal the secret."

So the fact that Lanir was severely tortured, kept the secret, and died in captivity did not surprise you?

"No, it didn't surprise me at all."

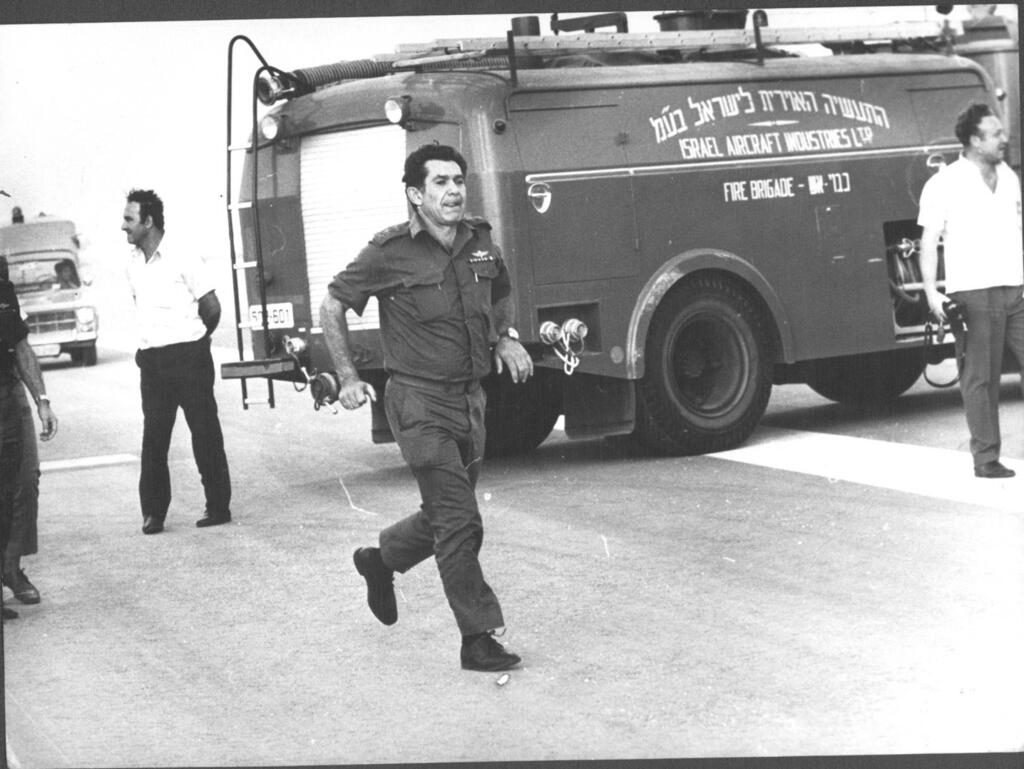

22 View gallery

An Israeli Skyhawk supports ground forces on Golan Heights front

(Photo: State Archives)

The story of Avi Lanir has been dramatically covered in foreign media and later became the subject of books and movies. Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Seymour Hersh depicted an apocalyptic scene in his book The Samson Option, describing a pilot—his interpretation of Lanir—tasked with a nuclear mission, standing at the edge of the runway, engines warmed up, ready to deploy the weapon over some Arab capital. This was all because Golda Meir and Moshe Dayan were convinced that a second Holocaust and the end of the Jewish state were imminent.

In his book The Sum of All Fears, Tom Clancy takes this scenario a step further: the pilot actually takes off to execute the mission. In the blockbuster film adaptation, the pilot looks at pictures of his two children, pulled from his flight suit pocket, as he ascends into the sky. These children bear a striking resemblance to Avi Lanir's own children, Noam and Nurit, as they appeared in October 1973.

However, these events never actually took place. Avi Lanir's Mirage jet was never equipped with the secret system, certainly not on Yom Kippur 1973. He never stood at the edge of the runway with it, and he never had to grapple with the decision to activate the device or potentially pay with his life and his plane.

On the other hand, a series of documents and testimonies, being published here for the first time, reveal that what actually happened at the Hatzor Air Base during those days was more significant than previously known.

Avi Lanir, a highly decorated pilot who had already participated in over 200 operational missions and had downed three MiGs, found himself trapped in a Syrian missile ambush that day. His Mirage jet was severely damaged by one of the missiles.

Although Lanir managed to steer the plummeting aircraft back toward Israel, he ended up parachuting into Syrian-controlled territory where he was captured. He was the highest-ranking pilot to be taken prisoner, but what particularly concerned the Israeli military and government leadership was the secret information he held.

According to later testimony by Yuval Ne'eman, who was then a special advisor to the chief of staff, Golda Meir told U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger that she was willing to give up the Golan Heights in exchange for the return of Lanir and the other 27 captured pilots. She didn't know, of course, that at the time Lanir was being severely tortured and had decided, as hinted at during a cockpit chat, to sacrifice his life rather than divulge any information.

Avi Lanir's body was returned from Syria to Israel in June 1974, showing signs of violence. Following a forensic examination and an extensive investigation by the intelligence security division, aimed at determining whether secrets had leaked to the Syrians—or, put more bluntly, whether Lanir had talked while in captivity—it was conclusively determined that he had not.

"We came to a clear conclusion that he did not speak, not a single word," says Col. (res.) Shimon Lavi, who was then the head of the intelligence security division. "He simply locked up completely, and the Syrians, getting nothing from him, tortured him until he could no longer be tortured."

The subject: "Awarding a Medal of Valor to Lt. Col. Avi Lanir, may he rest in peace," is the title of a letter from Benny Peled, the Air Force commander at the time, to IDF Chief of Staff Mordechai Gur. The letter was written in anticipation of a discussion by the High Committee for Medals of Valor shortly thereafter (see document in this article).

"After an extensive review of the circumstances surrounding Avi Lanir's death in Syrian captivity, I have come to the conclusion that I must recommend awarding the Medal of Valor to the commander of the 101st Squadron," Peled wrote.

22 View gallery

A letter by Air Force commander Benny Peled requesting to posthumously award Avi Lanir a Medal of Valor

(Photo: Private album)

"In his role as the commander of the 101st Squadron, Lt. Col. Avi Lanir had full access to sensitive information and was the only one among all the prisoners of the Yom Kippur War to possess such information."

Peled concludes that the system's secrets were carefully preserved, despite Lanir being "severely tortured and interrogated," and recommends awarding the Medal of Valor to his widow. In April 1975, his widow Michal received the medal on his behalf. Only a few knew then, and still know today, what secret he may have paid for with his life.

Much has been written, said, investigated, and filmed about what foreign media calls Israel's "nuclear option" in the Yom Kippur War. Most of the reports contain few facts and many myths, some bordering on fiction.

Even today, on the 50th anniversary of the war, the full story cannot yet be told. However, a series of recently declassified documents and protocols, both in Israel and abroad, allow for perhaps the first outline of how central the nuclear issue was to the war.

They reveal how it was used to apply pressure among the various states involved in the conflict, and also how, due to fears, panic and a series of mistakes, there was a concern for several hours that the Middle Eastern conflict might escalate into a global nuclear war between the Soviet Union and the U.S. No less.

Chapter 2: DEFCON II

Visibly distraught, officials began to arrive at the prime minister's office in the IDF headquarters for a discussion that started shortly before 3pm on October 7, 1973. The war had broken out just 24 hours earlier, and reports from all fronts were dire—casualties, wounded, prisoners, advancing Egyptian and Syrian forces. The Israeli leadership was in shock, but one minister was particularly despondent and disheartened, which would significantly influence discussions about the nuclear option during the war.

Defense Minister Moshe Dayan was flying from front to front throughout the conflict. Very early on, he came to some extremely grim conclusions about the situation—perhaps too grim. It has often been reported that General Rehavam Ze'evi said Dayan spoke of the "Destruction of the Third Temple," but this has been interpreted in various ways, and it has been difficult to determine whether Dayan truly felt this way.

However, an in-depth examination, using an information database of hundreds of thousands of pages set up for this research, along with artificial intelligence-assisted software, reveals that from the morning of October 7, Dayan repeatedly gave increasingly dire analyses of the situation on the battlefield. He was also the first to suggest, out of his despair, that more aggressive measures should be taken—measures that Israel, it is claimed, had refrained from using until that time.

Examples of the deep despair felt by the defense minister are numerous. Twenty-four hours after the outbreak of war, upon returning from a tour of the southern front, Dayan entered Golda Meir's cabinet meeting to share his perspective with other ministers and senior officials. None of them knew that Dayan had arranged for an additional person to wait outside the prime minister's chamber for the moment he might be needed.

Dayan stunned the attendants when he began by suggesting a significant retreat, proposing to establish a defensive and abandon the Suez Canal. He was certain that Jordan would enter the war, declared that the surface-to-air missiles were severely impacting the air force, and argued that the balance of power was unfavorable for Israel. Dayan also stated that the war would last a long time and that launching a counterattack under the current conditions was not feasible.

"I underestimated the enemy's strength, their military capabilities, and overestimated our own forces and their ability to hold," Dayan said. "We have a very serious problem with the balance of power. They (the Syrians and Egyptians) are fighting well and have good missile accuracy. This war is over Eretz Israel."

Ministers Yisrael Galili and Yigal Allon, who had never been Dayan's biggest supporters, were also present at the discussion. They were more optimistic, but Dayan continued. "In places where we can retreat, we will retreat," he suggested. "In places where we can't, we'll leave the wounded; whoever can arrive, will arrive. If they decide to surrender, they will."

Such statements had not been heard in Israel's defense establishment since the toughest moments of the War of Independence. "We don't have many tank operators or pilots; many people will fall... we have hundreds of casualties," Dayan continued. Then he threw out an enigmatic comment: "There might be other thoughts on how to act in this situation," but he did not elaborate.

Former IDF Chief of Staff Chaim Bar-Lev wrote in his journal about the event. "The prime minister told me that the defense minister, who had visited the front lines, returned and informed her that he admitted to overestimating the strength of the IDF and underestimating the enemy's capabilities. He believed the situation was dire. According to him, we needed to retreat to the Jordan border and hold the line until the last bullet.

“In the canal, we needed to fall back toward Egypt, and if that doesn't help, to resort to extreme measures, echoing 'let me die with the Philistines.' The prime minister seemed less shaken by the situation itself than by the volatility of the defense minister."

After Dayan, Chief of Staff David Elazar (Dado) provided an overview. It was more matter-of-fact, but still grim. His concern was that Egyptian forces would advance in Sinai and the Syrians in the Golan Heights, leading to "war within two to three days in Israel [proper]."

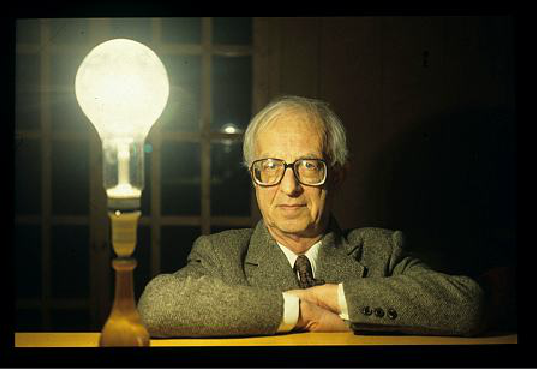

The discussion ended. Dado and military high command left the room. Dayan started to walk toward the door as if he himself was about to leave, but suddenly stopped, turned around and told those gathered about a guest waiting outside, whom he had invited to expedite matters. Standing at the door was Shalhevet Freier, head of the Atomic Energy Committee.

At this point, there's no official record. What happened in the room in the subsequent minutes was documented in a conversation held in 1995 between Azariahu Arnan, the close and faithful assistant to Yisrael Galili, and Ora Armoni, along with a series of notes written by Galili during the discussions.

Arnan recounted that "Moshe Dayan feared we were losing the war and tried to hint in a smaller forum—which included, besides Golda, Galili and Yigal (Allon)—that maybe we should, as a threat or a trial explosion or the like, warn the Arabs to be cautious... Both Galili and Allon told Golda that this was madness, that it shouldn't be done, and that we would win with what we've got. She accepted this view."

In notes he wrote to himself, Yisrael Galili described that "Moshe Dayan entered nervously" and that at the end of the discussion he turned to the prime minister and said, "Golda, we might need to be prepared with Dostrovsky's things (Israel Dostrovsky, the former director of the Atomic Energy Committee until 1971). We should prepare for activation of the thing, we'll discuss it further with you later."

The phrase "we should prepare for activation of the thing" needs explanation. Dayan is hinting at measures that require prior preparation, and what he didn't say is that he had already ordered the start of these preparations. Dayan spoke of some sort of trial or experiment to create a deterrent. Within this framework, he invited the current director of the Atomic Energy Committee to update on expediting the procedures.

"Let's stop talking about this subject," says Prime Minister Meir. But Dayan insisted, and according to Galili's note, "had a serious expression." Galili looked at the defense minister and wrote to himself, "Has he gone mad?"

Galili left the room agitated but then returned to ensure that Golda's instructions were clear to everyone. Meir called Shalhevet Freier and said in the presence of everyone, "Nothing without my approval."

However, the snowball had already started rolling. According to international reports, the covert actions taken by Israel at that time, along with its high state of alert equivalent to the United States' DEFCON II, were detected by U.S. intelligence services.

A detailed report on the subject was distributed among a select few high-ranking U.S. government officials. The report did not raise much interest because the Americans were convinced by IDF chief David Elazar's statement on the first day of the war that Israel would "break their bones."

According to Yuval Ne'eman, no decision was made to deploy what is described as "the nuclear arsenal," but he does not deny some level of preparedness for such a measure. He says the presence of Shelahvet Freier in the discussion was to consult with the prime minister at the onset of the war about what actions should be taken, including several precautionary steps in the nuclear domain, such as shutting down nuclear reactors for the duration of the conflict to minimize risks in case of an attack.

However, Dayan, increasingly despondent, continued to consider extreme measures. On October 9, he returned from the bloody southern front straight to a meeting in "the pit" at the IDF headquarters.

The time was around 4:30 in the morning, and the atmosphere was apocalyptic. According to witnesses, some officers broke down crying. Dayan provided another grim assessment and suggested recruiting even the elderly and young people while preparing for painful and deep retreats.

What else could be done? Dayan suggested, "Explore every option, even the wildest, that we could unleash on them—[censored] Damascus." Those attendants knew exactly what he meant.

The IDF chief also "wants to break Syria," he turns to Air Force commander Benny Peled and says, "Instead of whatever you're planning, Benny, target Syria tomorrow morning, [censored] Damascus, drop [bombs] inside Damascus, Homs and Aleppo, Latakia. I need a dramatic effect so that Syria will cry out. Someone has to yell 'stop the violence! They're destroying Syria.' Maybe someone will say, 'Stop, cease fire.' I have to break Syria now."

The rest of the meeting's minutes are heavily redacted, but assessments indicate that senior officers, including former IDF chief Yigal Yadin and Maj. Gen. Rehavam Ze'evi, suggested employing radical measures. Such discussions are not mentioned at all in the official historical records.

Brig. Gen. Aryeh Levi, the assistant to Deputy Chief of Staff Maj. Gen. Israel (Talik) Tal, entered his boss's office in tears. "Talik, you have to stop them; they will destroy the country... You must save the people of Israel from these loonies," he said. Tal promptly entered the room and managed to halt the discussion.

Aharon Yariv, former head of Military Intelligence, would later write that someone was "proposing a special idea against the Syrians." Yariv also opposed it, and Elazar decided against adopting the extreme measures against Syria.

In the morning, when the military and intelligence leadership returned to the prime minister's office, it became clear to them and to Galili that, following Dayan's directives, they had "declared a state of emergency—DEFCON II.” Shelahvet Freier was called in again and was told unequivocally, in the name of Prime Minister Meir, that "they can forget about it" and that it was time to "disperse the gathering."

Chapter 3: The classified document

But “the gathering" went nowhere. Interest in the nuclear issue continued to grow, but for a different purpose: to exert pressure on Israel's closest ally, the United States.

Israel, unable to decisively win the war, found itself in a severe shortage of weapons, ammunition, tanks and aircraft. The United States had promised to fill any such gaps, and Israel compiled a list of equipment and sent it to Washington. However, the U.S. was stalling. Prime Minister Meir attempted to pressure President Nixon and his Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.

Simcha Dinitz, Israel's Ambassador to the United States, was urgently summoned for a meeting with Kissinger. There he received troubling news: Kissinger explained that the U.S. would struggle to send Phantom jets while hostilities were ongoing and that maybe only two could be sent per day. As for tanks, it was completely out of the question for the time being—perhaps in a few more weeks. All of this was attributed to logistical issues, according to Kissinger.

In reality, the reason was different: U.S. Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger and his deputy opposed the shipment of weapons, fearing that such action would provoke the Soviets to enter the war. If that were to happen, the path to a third world war between two nuclear powers would be dangerously short.

Dinitz insists, and in the next meeting, held the following day, he tries to explain to Kissinger just how dire the situation in Israel is. "I want to tell you that we've suffered very heavy losses, both in manpower and in equipment from the SAM-6 missiles, which have been very effective against our aircraft... It seems to me that the human losses amount to over a hundred, maybe even reaching hundreds."

Kissinger, skeptical, asks him, "Hundreds?" Dinitz replies, "Yes, hundreds." He hands Kissinger a message from the prime minister, which states, "Our extraordinary military efforts have exacted a heavy price, especially in aircraft. We face a massive quantitative gap. Our aircraft are damaged and depleted. The prime minister urgently requests that you immediately begin supplying some of the new Phantom jets, at the very least."

Kissinger promised Ambassador Dinitz that he would do everything possible to get President Nixon to approve the weapons shipment, but that's not what actually happened. It turns out the president was, in fact, in favor of sending weapons.

"Let's give them some tanks," Nixon tells Kissinger, "It will give them great confidence." However, Kissinger wants to keep Golda Meir on a short leash and tells the president, "But not today." Nixon understands the difficult situation on the ground and says, "We can't allow the Israelis to lose."

Kissinger believes there's still time and recommends to the president to wait until Thursday, October 11. He thinks that Israel is exaggerating in its reports and that the situation couldn't be that bad. Dinitz meets him again the next day, telling him that Israel has lost around 500 tanks, and requests that the president urgently meet with Prime Minister Meir. Kissinger denies the request. He still believes that Israel is submitting hysterical reports.

Meanwhile, on October 10, the Soviet Union began airlifting supplies to Syria. In response, the Israelis increase their demands from the Americans, asking for no fewer than 80 Phantom jets and another 80 Skyhawk jets.

"The scarcity in both of these items is frequent and significant," claims a telegram from the Prime Minister’s Office. "The rate of attrition of our aircraft is so high that there is no possibility to delay this matter." But the Americans continue to drag their feet. The Pentagon is acting coldly toward the Israeli attacheés, and Kissinger still updates the president that Israel's shortage in materiel is not as critical as the Israelis claim.

"A feeling of almost despair," says Golda Meir in a meeting on October 12, when Israelis are convinced that elements within the Pentagon are hamstringing the airlift. "In the end, I know what the danger is," Meir says. "I say this with full awareness; in 1948, we did not face such a danger."

What’s next? They decide to send Washington an extremely urgent and classified cable, likely one of the most dramatic ever sent from Israel, if not the most dramatic. The cable is addressed to "Naphtali," the code name for Kissinger, and even today, 50 years later, extensive sections of the discussion that preceded the sending of the cable and the precise wording of what was written in the document itself remain classified.

For some reason, the cable has completely disappeared from the State Archives. Foreign reports have claimed that Israel raised the nuclear option in the cable. One thing is certain: after it was sent, the U.S. changed course, began sending arms to Israel, and the tide of the war finally turned in Israel's favor.

So what can be said about what was written in the cable? In an interview conducted by Reudor Manor on behalf of the Institute for International Relations with Yigal Allon in 1979, the interviewer asked about that cable and noted that he understands that as a result, the U.S. "finally decided to immediately send the airlift for fear that Israel might activate nuclear weapons. Are you familiar with this American response? Or the cable?"

Allon replies: "I remember that there was a cable that was decided upon in some informal forum of ministers; I don't remember its text. I do remember that it was a very serious cable, yes! That I remember..." Allon doesn't specify what exactly was written in the cable, but it appears that as a result, the Americans "feared that if we enter a state of despair, we would take an act of desperation, something they did not want to happen."

Yuval Ne'eman confirmed in an interview with Ronen Bergman that "in America... there is a kind of clause in the doctrine that says: Israel can always pressure the U.S. to provide it with conventional, routine equipment, by threatening that it might escalate to a nuclear posture."

What can be said is that the cable reached Dinitz, who was about to have another meeting with Kissinger, in a further attempt to obtain the arms that Israel so desperately needed. Dinitz was instructed to pull out the document only if there was no other choice.

On October 12th, at 11:20pm, Dinitz met with Kissinger. He reproached him for Israel's dire situation due to the delay in arms supply and accused Defense Secretary Schlesinger and senior Pentagon officials of intentionally holding back the shipment.

Kissinger decided to put on a little show for Dinitz, pretending as if he was unaware of the difficult situation, and asked his staff to get Schlesinger on the line. The voice of the defense secretary—incidentally, he, like Kissinger, was also of Jewish origin—was heard on the speaker. "Okay, that's it—when are they going to start running out of supplies?" he asked hesitantly, as if Israel hadn't been shouting for days.

Kissinger, trying to be the good cop, said, "They are out of supplies now. They have stopped their offensive. And they are now in dire straits in Sinai. My information is based on a cable from the prime minister to the president. And you know that it may not be true, but it's a terrible responsibility to take."

The conversation ended ambiguously, and Dinitz assumed that it was all staged to buy more time. His only remaining option was his trump card: the document in his pocket. He requested to be left alone with Kissinger. Everyone present, including the aides and the stenographer, left the room. Some claimed that in this conversation, Dinitz told the secretary of state that it was either an airlift of supplies or the risk of a third world war; Israel would have no choice but to initiate it.

In an interview that Ronen Bergman conducted with Kissinger about four years ago, the secretary of state initially feigned ignorance, then denied any knowledge of Israel's nuclear posture, and said that Dinitz did not try to blackmail him. He claimed that the information had never reached him.

Either way, Dinitz left the meeting at 12:23am and upon his return wrote to Prime Minister Meir. He described the meeting with Kissinger as the hardest of his life, and that "the one-on-one conversation had the same spirit and atmosphere as when Naphtali paces a room like a caged lion."

Incidentally, on the American side, there is no documentation, even in retrospect, of the document, or a summary of the one-on-one conversation; not even of Kissinger's conversation with Nixon immediately afterward. "The document was not located," was the response in the database of the State Department's archives.

What is clear is that the document Dinitz had in his pocket had an almost magical influence on the entire American leadership. By 1:15am, Kissinger calls Dinitz and says precisely the opposite of what he had said just two hours earlier: all problems have been magically solved, there are no logistical difficulties and no objections.

22 View gallery

American Starlifter C-141 cargo plane arrives in Israel with military supplies during Yom Kippur War

(Photo: IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

Under presidential directive, ten C-130 cargo planes were immediately dispatched to fly directly to Israel, along with another 20 charter flights. The rest of the equipment would be shipped to regional islands and loaded onto El Al flights to Israel. Simultaneously, the Pentagon summoned IDF representatives to transfer ten Phantom jets to them within a matter of hours, the first shipment of many.

The next day, Kissinger would announce in a special meeting that the President would not tolerate any more delays at the Pentagon, otherwise, "we want the resignations of the officials involved."

The airlift got underway, and Israel was able to afford itself the flexibility to exploit developments on the battlefield to launch a counter-offensive, cross the Suez Canal and even threaten Cairo. However, the nuclear issue remained on the table.

Chapter 4: The Jericho ruse

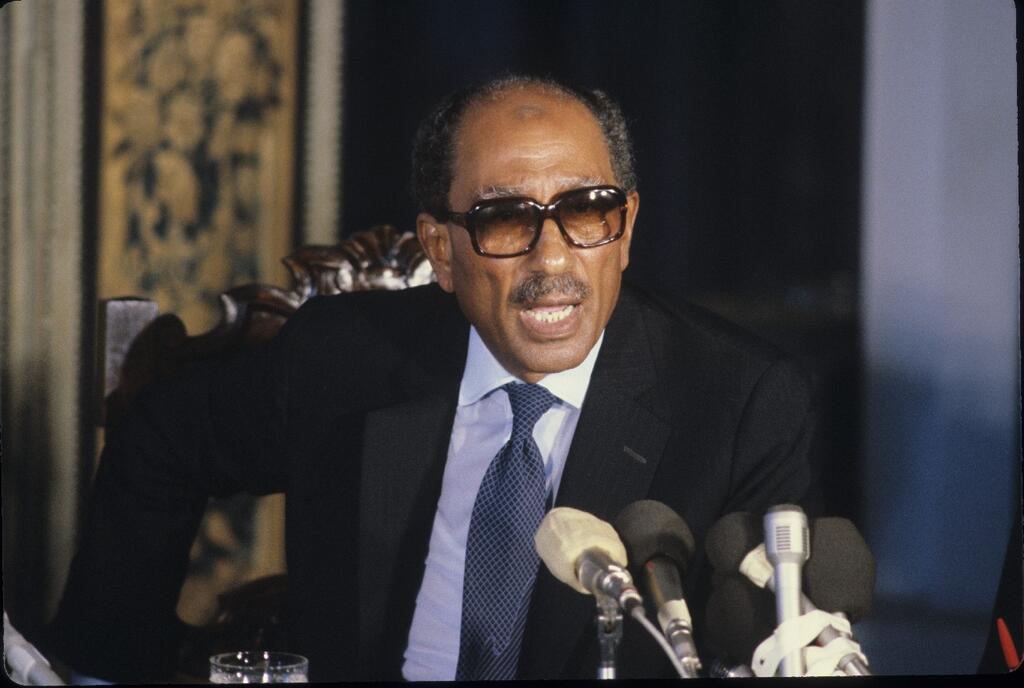

On October 16, when Egyptian President Anwar Sadat realizes that the momentum of the war is turning, he threatens to launch ground-to-ground missiles at Israel. According to him, these are Egyptian-developed Al-Zafar missiles, and they are "capable of crossing Sinai... deep into Israel."

Israel is unfazed at first, as according to intelligence, the Al-Zafar missile project — which was developed with the help of Nazi German rocket scientists — is not yet operational. Intelligence estimates suggest that these are Soviet Scud missiles, of which several dozens had been supplied to Egypt. Dangerous, but not a game-changer. But then, Zvi Zamir, the head of the Mossad, receives a phone call.

His top spy in Egypt, Ashraf Marwan — an agent about whom there remains bitter debate regarding the information he provided and how he was handled — requests a meeting. The last time, 12 hours before the war broke out, Marwan had warned him that Egypt and Syria were about to attack. What will he say this time?

In the secret meeting, which for some reason Zvi Zamir omits from his account, Marwan claims that the Egyptian army has no fewer than 400 Scuds aimed at Israel.

Marwan had previously reported that Sadat had only 20 Scuds, but Zamir doesn't ask too many questions, such as how the number suddenly jumped to 400 missiles, or why Marwan arrives with this news just a few hours after Sadat's threat, which essentially supports Sadat's public statements and is supposed to deter Israel from attacking Egypt.

The information reaches Israel and triggers a chain reaction that almost ends in disaster. During a meeting at the IDF General Staff on October 18, Deputy Chief of Staff Israel Tal asks, "In a desperate situation, won't they use gas? (in the warheads of the Scuds)".

Aharon Yariv, former head of Military Intelligence, responds, "Yes, and they'll also target Tel Aviv with a Scud. As of last night, the Egyptians understand that their situation is dire."

Prime Minister Meir instructs Dinitz to update the United States on the developments and to pass on a request to Kissinger: that the Soviets should warn Sadat that firing Scud missiles or using chemical weapons would elicit a serious response from Israel. What kind of response? It's not specified.

Kissinger takes the threat seriously. During those days, the American intelligence community employs all means, including wiretaps, satellites and their most powerful secret intelligence-gathering tool — the "Blackbird," the fastest airplane ever built — to verify the happenings in Egypt.

The Americans indeed confirm, through Blackbird reconnaissance and satellite imagery, that Egypt has deployed several Scud missiles in the Nile Delta that could reach deep into Israel. But suddenly, this becomes the least of their concerns. The images are sent to several American intelligence analysis units, including one specializing in identifying Soviet vehicles. Analysts conclude that the vehicles used to deploy the missiles are the same kind used for launching nuclear-tipped missiles. This alarming information is passed to the CIA's office at the U.S. Embassy in Tel Aviv, where they decide to share it with Israel.

"The Americans told us, 'What you're seeing here is essentially a Scud unit with nuclear warheads’," recounted Prof. Yuval Ne'eman, who was invited to the embassy to view the images. "The Americans gave us this picture and told us, 'There might be nuclear warheads on those Scuds’."

Shaken, Ne'eman quickly presented the dramatic information to Golda Meir and the cabinet, and later also to army chief Dado. "Dado ordered the deployment of the Jericho missiles," Ne'eman wrote, "and requested that they be positioned so that they could be clearly seen in satellite images. This way, the Russians, who were launching a new satellite every two days, could photograph them. The intent was to let them know, without explicitly stating, whether or not we had suitable warheads for these missiles, but that the missiles were ready."

This is high drama. If Israel fears it is about to be attacked with a nuclear Scud, and according to Ne'eman's account, exposes its Jericho missiles to create the impression that they are nuclear-tipped – this is a very dangerous global game, one that makes the Cuban Missile Crisis look almost like comedy in comparison.

According to foreign reports, then – as now – the Jericho missiles, which can be fitted with nuclear warheads, were stored at a secret Air Force base near Beit Shemesh.

If the reports are accurate, it's likely that the base commander convened a meeting with senior officers on that particular evening. The commander briefed his team on the need for actions that would not be related to an immediate threat or actual combat. Instead, the focus would be on drawing the attention of American and Russian satellites. The goal was to provide Henry Kissinger with additional justification for escalating the airlift, while also giving the Russians a compelling reason to be concerned.

At the missile base, troops put on a show specifically designed to be captured by Soviet satellites. According to reports, a truck carrying a Jericho missile executed maneuvers in the yard of one of the bunkers. The missile was likely fitted with a dummy warhead, meaning it was not armed and would not detonate. The truck moved back and forth, raising and lowering the missile, all while in plain sight—without the usual shielding that prevents satellite imaging in similar circumstances.

Dino Brugioni, who at the time headed the National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC) for American Intelligence and was considered a guru among imagery intelligence analysts, wrote, "We observed activity at the Jericho missile base, and the CIA believed the missiles were armed with nuclear warheads."

Maybe yes, maybe no, but it seems likely that Israel did not yet have the capability to launch such missiles at the time, and the whole thing at the base was essentially a staged performance for Russian satellites. The Russians were supposed to interpret the images, become alarmed and instruct the Egyptians not to use their Scuds missiles. However, things didn't unfold as planned.

Instead of becoming alarmed and advising the Egyptians not to use their Scud missiles, the Soviets interpreted the maneuvers at the Israeli missile base as preparations for an attack and readied themselves for a counter-attack.

American intelligence intercepted Red Army orders to the commander of a strategic ground-to-ground missile brigade near Kyiv in Ukraine. The orders were to deploy and prepare to launch 12 missiles targeted at the Ramat David base, the nuclear reactor in Dimona and the oil refineries in Haifa.

The brigade commander later informed a colleague that the orders also included replacing the warheads with conventional ones, but this detail, if true, was not picked up by the Americans. From their perspective, Moscow was considering using nuclear weapons against Israel.

Dino Brugioni compared the Yom Kippur War to another crisis, stating, "I lived through the tense days of the Cuban Missile Crisis, but I must admit there were times when the tension during the Yom Kippur War matched or even surpassed that of the crisis in Cuba."

Israeli leadership was concerned that even if nuclear missiles were not in play, Sadat might resort to using Scud missiles equipped with chemical warheads if he realized the Egyptian army was on the verge of collapse and all his war gains were about to be wiped out.

Prime Minister Meir instructed Dinitz to convey a message to Henry Kissinger for relay to the Russians. "Sadat, who bears heavy responsibility for initiating the war, will bear even greater responsibility if he uses weapons of mass destruction like ground missiles or gases. Israel will find a way to respond," possibly hinting at nuclear retaliation.

The Russians did respond, but again, not as expected. They put all seven of their airborne divisions on alert and issued a warning to Israel to withdraw its forces, or else face "the most serious consequences." In Jerusalem, this was interpreted as a Soviet nuclear threat against Israel.

On October 22, shortly before the cease fire, Egypt and the Soviet Union aimed to underscore the gravity of their threats by launching three Scud missiles equipped with conventional warheads.

22 View gallery

Israel and Egypt sign a cease fire at the end of the Yom Kippur War

(Photo: gettyimages)

One missile exploded near El-Arish, while the other two exploded on the eastern side of the canal, close to the bridgehead. One of these latter missiles resulted in the death of seven IDF soldiers.

The official cease fire took effect on that same day under pressure by the Soviet Union. However, Israel violated it by encircling the Egyptian Third Army, with tacit American support. Moscow was enraged and warned Israel of the "most severe consequences" for its continued offensive actions against Egypt and Syria. Brezhnev issued an ultimatum: either Soviet and American forces would be deployed to enforce the cease fire, or the Soviets would "be compelled to urgently consider taking unilateral actions."

The Russians expected the Americans to quickly enforce the cease fire, but Washington interpreted the Soviet message as a threat against them. In his memoirs, Nixon wrote that Brezhnev's words represented, "perhaps the gravest threat to U.S.-Soviet relations since the Cuban Missile Crisis 11 years prior."

Once again, the situation began to deteriorate. American intelligence detected preparations by Soviet air and naval forces, including the addition of seven dock landing ships and two helicopter carriers to the Soviet fleet in the Mediterranean, as well as the delivery of additional Scud missiles to Cairo.

However, the most concerning information came from secret sensors deployed by American intelligence at the bottom of the Bosporus Strait. The Soviet naval vessel Mezhdurechensk activated all sensors indicating it was carrying nuclear armament. The ship arrived at the port of Alexandria on October 24, where it was subsequently located the next day by another overflight of the Blackbird spy plane. The Americans assessed that the ship was carrying nuclear warheads for Egypt's Scud missiles.

The Americans were concerned that if such missiles were launched, Israel would respond with its own missile strikes. As a result, President Nixon ordered the U.S. to prepare for the possibility of World War III and to engage in assertive military action, sending a clear message to the Soviets that the United States opposed any unilateral moves.

Approaching midnight on October 24, the U.S. president DEFCON III, the highest state of readiness since the Cuban Missile Crisis.

However, concurrently, the U.S. conveyed a message that it would no longer overlook Israel's violations of the cease-fire. Finally, on October 25, the war came to an end. As peace talks between Egypt and Israel commenced, Nixon ordered the de-escalation of the nuclear readiness level.

To this day, it remains unclear what was actually onboard the Mezhdurechensk that triggered the sensors, and whether all the nuclear tension and pressure on Israel to end the war—despite its potential ability to perhaps even capture Cairo—was a result of a technical glitch in a sensor deep in the waters of the Bosporus.

Special thanks to Adam Raz and Pesach Malovany for their assistance in locating documents for the research, aided by Google's Pinpoint.