The protagonist in Mendele Mocher Sefarim’s book "The Travels of Benjamin III," dreamed of making his fortune by locating the lost tribes of Israel. The satirical novel imagines the young Benjamin unsuccessfully searching for the Sambatyon River and the “Land of the Red Jews” (“Rote Juden”).

With his sidekick, Sendrel, Benjamin wanders from village to village, eventually setting sail in a fishing boat on a river named “Sirakhon,” believing it to be the mythical Sambatyon River, mentioned in rabbinical sources.

In his 1878 book, Mendele Mocher Sefarim not only sought to regale the myths relating to the ten lost tribes, he also wanted to draw attention to the idle and degenerate culture prevailing in the Jewish villages of Eastern Europe. Mendele’s Benjamin goes out on a quest to find the ten lost tribes that were torn away from the Jewish people 2700 years ago.

The mystery surrounding the dream of finding, and thus determining, the fate of these lost tribes has charged the imagination of generations of writers, researchers and adventurers. From time to time the desire to find the tribes peeked as stories and fragmentary pieces of information surfaced, compounded by reports that these tribes were living happily, adhering to ancient Hebrew customs.

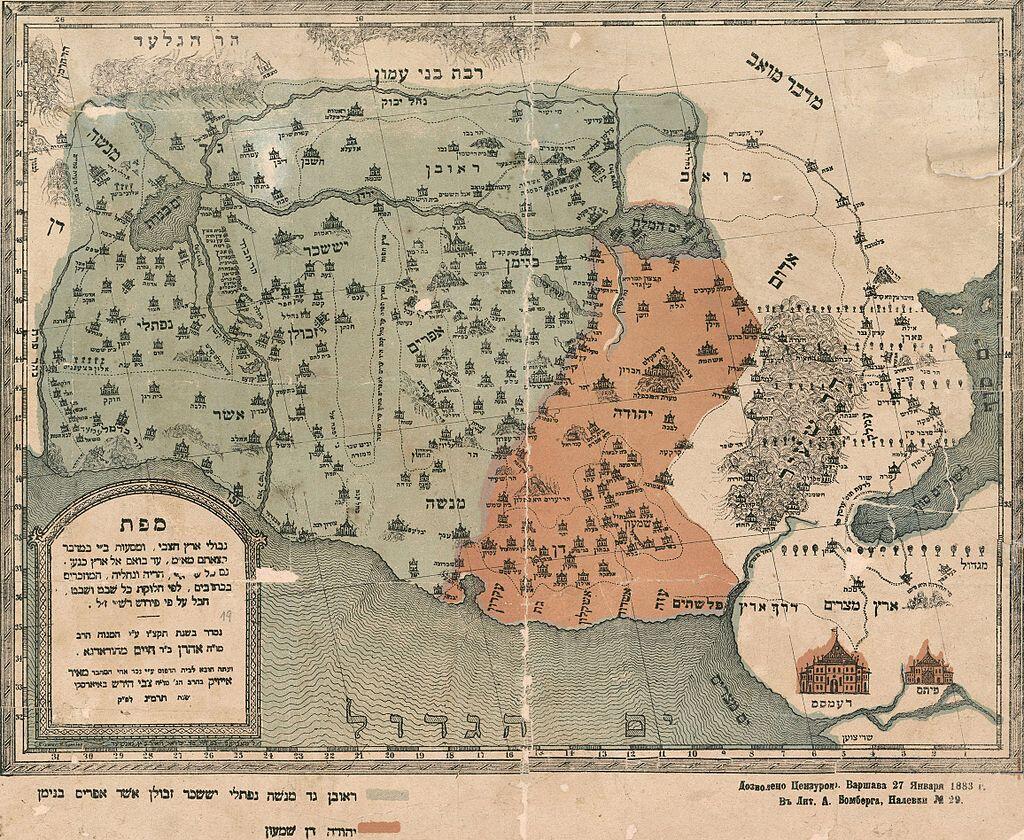

The story begins with the destruction of the Biblical Kingdom of Israel (independent of the Kingdom of Judah) in 722 BCE. The Second Book of Kings recounts how Shalmenezer, king of Assyria, exiled some of the residents of the Kingdom of Israel.

“In the ninth year of Hoshea, the king of Assyria captured Samaria and deported the Israelites to Assyria. He settled them in Halah, in Gozan on the Habor River and in the towns of the Medes” (2 Kings 17:6. Repeated in 1 Chronicles 5:26). This exile is further attested in Assyrian records as well as in the prophesies of the Biblical prophet Isaiah writing following the fall of the Kingdom of Israel that Jews would return to the Land of Israel “from the north, some from the west, some from the region of Aswan” (Isaiah 49:12).

As time passed, tales multiplied as did reports from daring individuals who went looking for the tribes. It seems like anyone engaged in the search was disappointed. They invariably found themselves obsessively delving into a sea of sources, unable to give up their dream. Some tried to redeem the tribes by bringing them back into the fold of the Jewish people. Others sought their own redemption through the tribes.

One redemption involves the story of 11th century Rabbi Meir bar Yitzchak Shatz Nehorai. Rabbi Meir was a cantor in Worms (Vermayza), Germany and is best known for penning the Akdamut liturgical poem which is recited in synagogues to this day. His life story is shrouded in mystery and some sources claim that he conducted a rescue mission beyond the Sambatyon River.

At the time of Rabbi Meir, the splendid Jewish community of Worms found itself in grave danger due to a certain monk who hated Jews who had persuaded the king to kill them all unless they convert to Christianity. Facing tragic consequences, the community obtained an extension to allow them to bring a learned Jew capable of holding a disputation with the monk so as to revoke the ruling. At the time, it was known that there was only one man who could debate the monk: a man who was a member of the ten lost tribes residing beyond the Sambatyon River. No one knew where the river was or how to cross it.

Stories about the mysterious river appear in rabbinical sources dating to the Second Temple period as well as in the writings of Josephus and further sources. The river, the stories say, rages with rapids and throws up stones six days a week, so that it cannot be crossed. On Shabbat the torrents stop, granting the river its name. However, the river cannot be traversed on Shabbat either, due to the halakhic prohibition of crossing a river on Shabbat. Week after week the river rages, beyond it trapping the ten tribes who are unable to reunite with the rest of the Jewish people.

To save his community from destruction, Rabbi Meir took on the challenge of finding the lost tribes. He made his way from the lands of Ashkenaz to Jerusalem to find the wise elders who would direct him to the river. With these instructions, he set out on his way, managed to get as far as the river, but found the river raging. He waited for Shabbat when the river instantly calmed transforming into a calm lake. Although it is forbidden to cross a river on Shabbat, this rescue mission had earned a dispensation on grounds of “pikuah nefesh” (saving a life).

When Rabbi Meir crossed the river however, he ended up sacrificing himself: He reached his brethren, members of the ten tribes, who immediately agreed to send the required man to save the Ashkenazi community. The Red Jew was allowed to cross the river on Shabbat, but Rabbi Meir, who had completed his mission, was not.

So, Rabbi Meir was compelled to stay with the ten tribes. After giving the man directions, he was filled with divine inspiration and compiled the Akdamut. He gave the poem to the Red Jew who left for Ashkenaz where he reached the king and presented himself before the evil monk, won his disputation, saving the Jews of Ashkenaz. All this occurred close to the Shavuot holiday when the poem is still recited in synagogues.

Even a tomb attributed to the rabbi-poet in the Galil doesn’t seem to detract from the charm of this tale of self-sacrifice. One could argue that the Galilean tomb isn’t truly that of Rabbi Meir, especially as some claim he’s buried in Poland anyway. The impression left by his works and activities seems to warrant more than one burial place.

The story of Rabbi Meir is just one link in a long chain of tales of travelers finding their way to or from the ten tribes. A further prominent story is that of ha-Dani. Although Eldad is supported by historical sources, like Rabbi Meir, he leaves behind a life story shrouded in mystery. His writings were widely circulated and were even ardently read by Mendele Mocher Sfarim’s Binyamin III before commencing his voyage.

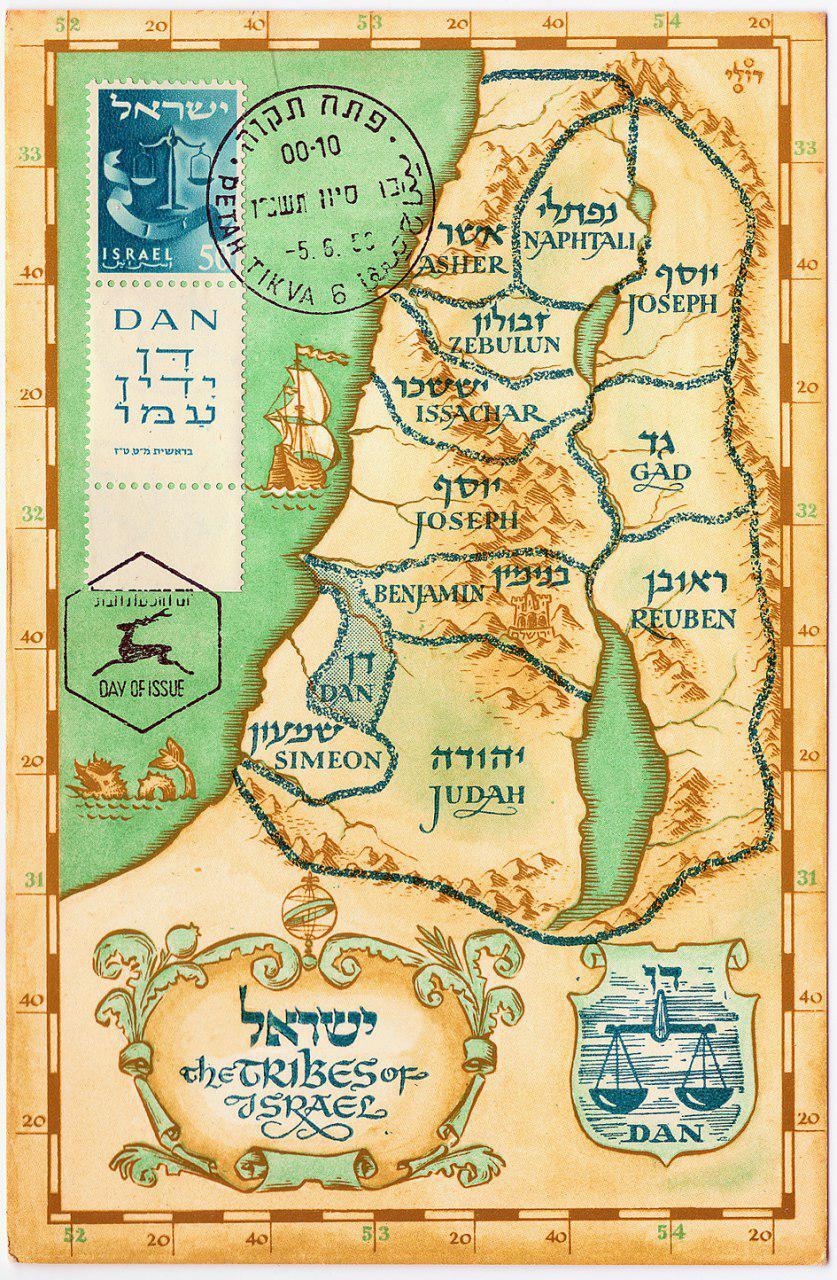

Eldad lived in the 9th century and claimed to hail from the Tribe of Dan. He describes the lives of the four exiled tribes of Asher, Gad, Naftali and Dan beyond the Mountains of Kush. He claims that the four tribes were living happy and prosperous lives, that they had precious stones, silver and gold, camels and cattle. They grew olives, pomegranates, pulses and watermelons. They had six springs that they used to water their crops. They had no impure animals, fleas or flies. They all lived in grand homes and sewed no end of lovely clothes.

They had neither slaves nor concubines as they were all equal. They didn’t lock their houses at night as there are no thieves among them. They all lived to that age of 100 or 120 and no son predeceases his father. They had a white flag with “Shema Israel” written on it in black and had never set eyes on a pagan and the member of no other nation had ever seen them as they were surrounded by the Sambatyon River which cannot be crossed.

The obvious question is if Eldad hailed from the tribes beyond the river, how did he cross it to tell the tale to the Jews of Spain and North Africa? Eldad responds with the following story:

He boarded a small boat on a trade journey with Jews from the tribe of Asher. In the middle of the night, a storm raged rocking the boat until it broke. Eldad and his friends managed to hold on to a wooden plank and floated to dry land. They found themselves in a land of man-eating giants who were as black as crows. At this stage, the luck of his large, healthy, well-built friend ran out as the cannibals started eating him alive. They attached a collar to the thin and weak Eldad and, to fatten him up, they placed large quantities of food in front him but. Knowing his fate if he were to gain weight, he ate almost nothing.

After extended agony, God sent an army of the cannibals' enemies who defeated them in battle. The new troops also took him captive but didn’t harm him, but rather dragged him from one country to the next until a certain Jew paid 32 pieces of gold to redeem him.

At the end of the 19th century researcher, Abraham Epstein, edited the works of Eldad ha-Dani and critically investigated the geographic locations mentioned. He concluded that Eldad came from Eastern Africa, near the Gulf of Aden. If this conclusion is correct, his story of cannibalistic tribes is perhaps less fantastic.

The famed traveler, Benjamin of Tudela (Binyamin Metudela) also tells courageous success stories relating to the ten tribes. In the mid-12th century, he set out on a decade-long journey. In his book The Travels of Benjamin he writes that the tribes had states and vineyards, gardens and orchards. They were not oppressed by gentiles. They had one leader named Yosef Halevi. They would go to war through the desert and had an alliance with one nation whose men had no noses, but rather two small holes from which the wind would come out. He also describes as invasion by the King of Persia followed by drawing up a treaty with him.

If Mendele Mocher Sfarim’s hero in Benjamin III follows in the footsteps of Binyamin Metudela, who would be the first Benjamin, then who is the second Benjamin? This is 19th century adventurer Israel Yosef Binyamin (JJ Benjamin) from Moldova who went on a quest to find the lost tribes. He was an unsuccessful lumber merchant, who left his pregnant wife to travel the Levant. In his book Eight Years In Asia And Africa From 1846 to 1855, he writes about the tribes he visits and describes the conditions of the Kurdish and Moroccan Jews. Upon his return and the publication of his book, he contacted British and French rulers seeking help for Jews of the Levant.

A further dramatic account of meeting members of the lost tribes is provided by 19th century traveler, Dr. Joseph Wolff, a highly educated Jew who had converted to Christianity, became missionary, and was devoted to finding the lost tribes.

In his book, Narrative of a Mission to Bokhara, he writes that on is travels, he was attacked by thieves who stole his possessions and planned to kill him, and took him to a city named Torbad. Upon entering the city, he noticed a large crowd and he cried out “Shema Israel.” He found himself immediately surrounded by the crowd, excited by his ancient exclamation. They freed him from the thieves and invited him to their homes where they told him that they were descendants of the ten tribes. As a missionary, Wolff tried to persuade them that Jesus is the son of God and was surprised to learn that they had never heard of him. This, along with further customs, convinced him that they were indeed members of the lost tribes.

Binyamin Metudela, like other travelers, refers to a river surrounding the tribes. Throughout the generations, the legends about the tribes include the river and its miraculous qualities. Apparently, these qualities are in place not only when the water and sand are in their natural environment, but also when drawn from the river and transported in a vessel to some other place, where the sand rattles in the vessel stopping only on Shabbat.

An unverified, yet widely cited, quote attributed to Maimonides reads: “With regard to the question about the tribes, you should know that this is a true issue and we wait for their arrival, for they are hidden beyond the mountains of darkness and the River Gozan and the River Sambatyon.” He continues to tell of sand brought from the river that moves around for six days and rests on the seventh day.

For generations following Maimonides similar stories, both old and new, circulated. One such story is attributed to Menasseh ben Israel, 17th century writer and leader of the Jewish community in Amsterdam. Born in Lisbon to a Converso family, he is quoted as saying: “In my hometown, there was a Kushite man who had a glass vessel filled with sand from the Sambatyon River. The sand would jump around in the vessel during the week and as Shabbat came in, the Kushite would go to the street where the Conversos were secretly keeping their religion and would show them that the sand had stopped. The Gentile would use this miracle to bring a sign to the Jews that the Holy Day had started, helping them keep Shabbat.”

Into the 20th and 21st centuries, people have continued writing and dreaming about the tribes. The State of Israel’s second president, Yitzhak Ben Zvi, was keen to research the mystery of the tribes. He went on expeditions and interviewed people. His book, The Exiled and the Redeemed: The Strange Jewish ‘Tribes’ of the Orient, detailing ancient Hebrew communities including the lost tribes, earned him the 1953 Bialik Prize for Jewish Thought.

Further books collating stories and accounts of the tribes have been published in more recent decades including Avigdor Shahan’s 2003 bestselling Across the Sambatyon – A Journey in the Footsteps of the Ten Lost Tribes and Rabbi Eliyahu Avichail’s 1987 The Tribes of Israel: The Lost and The Dispersed. Rabbi Avichail went on to found the Amishav foundation to help bring hundreds of members of the Bnei Menasseh community from north India to Israel.

In 2018, the minister for diaspora affairs commissioned a comprehensive report investigating the non-Jewish communities who have a special affinity to the Jewish People. The report mainly dealt with descendants of Conversos (especially in South America) who are interested in connecting with Judaism. The report also addressed Bnei Menasseh and called for more research and building stronger ties with communities with partial attachment to the Jewish people.

The question as to whether the lost tribes would unite with the Jewish People and return to the Land of Israel was addressed by the sages of the Mishna and Talmud. As to be expected, there was disagreement: Rabbi Akiva said “they are going and not returning” to which Rabbi Eliezer responds: “What today overshadows and illuminates, even the ten tribes that are dark for them… He will enlighten them” (Sanhedrin 10:3).

If we are to accept a widely held hallachic notion that the Ethiopian Jews are the descendants of the Tribe of Dan, and the claims of the communities in north India that they are the Tribe of Menasseh, some of the descendants of these tribes have already returned. Time will tell whether further such communities will be found and verified and if they return to the homeland from which their forefathers were exiled 2700 years ago. Either way, their story is still here and is forever sprouting fresh branches.

The writer is the author of the historical novel The Garden Within and Nobody’s Place (both published by Kinneret Zmora-Bitan)