Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Despite some positive changes in recent years, Holocaust survivors still struggle to receive vital services and live out the rest of their lives in dignity amid a very challenging Israeli reality.

As the country prepares to mark Holocaust Memorial Day later this week, it is time to consider what more the country can do to help the survivors live out their remaining days without suffering.

"The average age of Holocaust survivors is 85," says Ety Farhi, CEO of the Foundation for the Welfare of Holocaust Victims.

"This means they do not have many more years to live. The traumas of the Holocaust were compounded by the coronavirus pandemic, which along with their advanced years, has added to their sense of loneliness and has brought on a deterioration in their physical and cognitive health," she says.

"The advances in digital technologies, challenging for the elderly, further add to their isolation," she adds.

The foundation assists some 70,000 survivors and has mapped their most common needs. "Government ministries are doing their best to accommodate the needs of the survivors, but many do not have the time to wait for bureaucracy to work for them. They need help now," Farhi says.

"We require the resources to deal with the problems, which prevent them from a life with dignity."

Officially, Israel says there are 7,500 survivors who are solitary and who struggle with day to day challenges, although the foundation believes that number may be even greater.

"Our survey shows 10% of survivors say they have no family and are on their own," Anat Shuster, head of social services for the foundation, says.

"The National Insurance classifies a person who is solitary, as someone who has no living children, but we also count those whose children are estranged or live outside Israel, and those who have no support system in place," she says.

One of those survivors is Karolina Moshe, who wants to leave her third floor apartment over inaccessibility. The 86-year-old Holocaust survivor has no elevator and finds the stairs too difficult to navigate.

"I cannot go outside unless someone comes with me," the Romanian-born woman says. "I am very lonely," she adds.

"I cannot even tell you what season we are in. I would love to have someone who could help me out at home a bit and walk out with me," she says.

"Loneliness is very difficult. I have no family and no one to greet in the morning or say goodnight to at the end of the day. My husband passed away 30 years ago, and I've been on my own since. I have one son, but he lives far away, and we hardly see each other," Karolina says.

"Most of all, I would like some company. Someone to talk to. Someone who can bring me something I need. Just someone who will knock at the door," she says.

"As a child, I remember always being hungry for a bit of bread," she says. "I don't remember ever laughing because I witnessed things children should never see. After the war, we fled to the Romanian capital and from there to Israel," she says, adding that more money should be invested in helping survivors.

As they age, the needs of Holocaust survivors grow and their living conditions must be adapted to the changing situations.

"Most of the apartments used by the survivors are unsuitable," Shuster says. "They do not have proper showers they can use if they are unable to walk, and such adaptations cost thousands of shekels, beyond the reach of most."

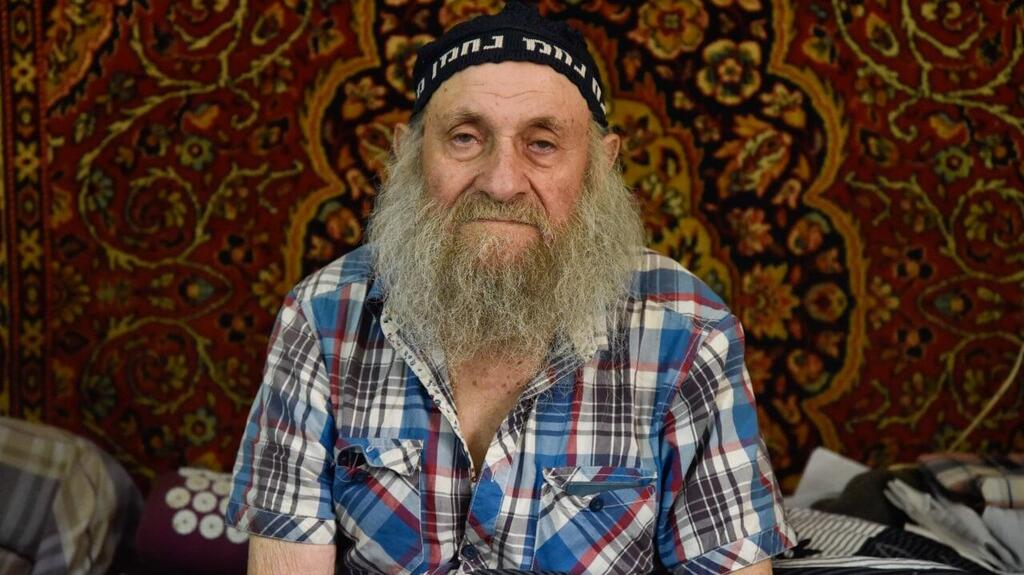

Yaakov Katz, 83, who fled Odessa when he was four, finds the recent war in Ukraine especially difficult.

"We traveled through Mariupol where my sister died of hunger. Mother would give us corn seeds to eat. Seeing the war there is very difficult for me."

Yaakov had both legs amputated because of a blood disease and suffers phantom pain constantly. He receives a few hours of help a day, but needs someone to be with him all the time.

"I have four sons, grandchildren and great grandchildren and they help as much as they can," he says. "But I live alone and the help I receive from the National Insurance, is not enough. I cannot cook or clean by myself and if I am in bed and want a drink of water, I cannot go to the kitchen, and must wait for someone to come," he says.

"With technological advances and the digital world becoming a necessity, the survivors are left behind," Shuster says.

"They cannot order food online, access their bank accounts, book appointments or contact government offices. Even social contact online is out of their reach," she says.

Michaela Shemer was born in Bulgaria and came to Israel in 1961. "I try to lean the new technology but am struggling," she says. "I needed a medical document and could not access it and had to wait for a woman who comes in only three days a week, to help me," she says.

"The more I am able to learn, the easier thigs become. I've mastered the tablet and can communicate with my family abroad and read interesting articles," she says.

After two years of the coronavirus pandemic, Holocaust survivors find they have been increasingly isolated and find it difficult to resume any contact with the outside world.

"The pandemic brought up their past traumas," Shuster says. "Even those who have family who visits a couple of times a week, are alone most of the time."

Jenny Rosenstein was very active before the COVID pandemic struck, but had to stop giving lectures when her medical condition deteriorated.

"My days are hard and I suffer from pain. I sit at home all the time, in bed with a hot water bottle. That is not how old age should be spent," she says.

"I have two wonderful children who visit me and bring me what I need. But I cannot leave the house and I am lonely.

"When I have visitors, I regain confidence and feel much happier. I miss interacting with people, having conversations, telling my story. We've been through so much in life, we've given so much to the country, we should not be cast aside," she says.

"I want justice for all of us. Not may of us are left," she says.

"As a child in Romania, we were forced to remove the gold teeth from people who were executed by the Nazis. I remember the stench of when I was just six years old," she says.