Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Mansour Abbas joined Israel’s current coalition government for moments such as last Monday night.

As the Knesset pulled an all-nighter debating the renewal of the Citizenship and Entry Into Israel Law that bans the automatic granting of citizenship to Palestinians who marry Israeli citizens, Abbas, head of the Islamist Ra’am party, negotiated a compromise with his coalition partners to extend the law by just six months instead of one year and to work to find humanitarian solutions for thousands of Palestinian spouses living in Israel on temporary residence permits.

Arab leaders roundly criticized Abbas when he negotiated first with Benjamin Netanyahu and then with Yair Lapid and Naftali Bennett to become part of the coalition. But he said he was choosing pragmatism over the ideology of remaining on the outside of any Israeli government.

As part of the government, he reasoned, he could help his constituents get the things that they needed, such as money to improve their communities and schools, affordable housing and police to collect illegal weapons and bring down the high crime rate in Arab communities.

In fact, the coalition agreement between Abbas, whose Ra’am party has four seats in the 120-member Knesset, and Bennett and Lapid pledges over $15 billion for infrastructure, education and initiatives to reduce crime in the Arab community and makes Abbas chairman of the Knesset’s Special Committee on Arab Society Affairs.

Right-wing opposition lawmakers also were unhappy with a government that includes as a full member an Arab party, for the first time ever. And they were reminded of this early Tuesday morning as the controversial family reunification law was not renewed.

Though, to be fair, it did not pass in part because those same right-wing opposition lawmakers voted against the law in an effort to embarrass the government and criticize Ra’am’s presence in it.

Abbas and one other Ra’am lawmaker voted in favor of the law due to the compromise; two Ra’am Knesset members abstained.

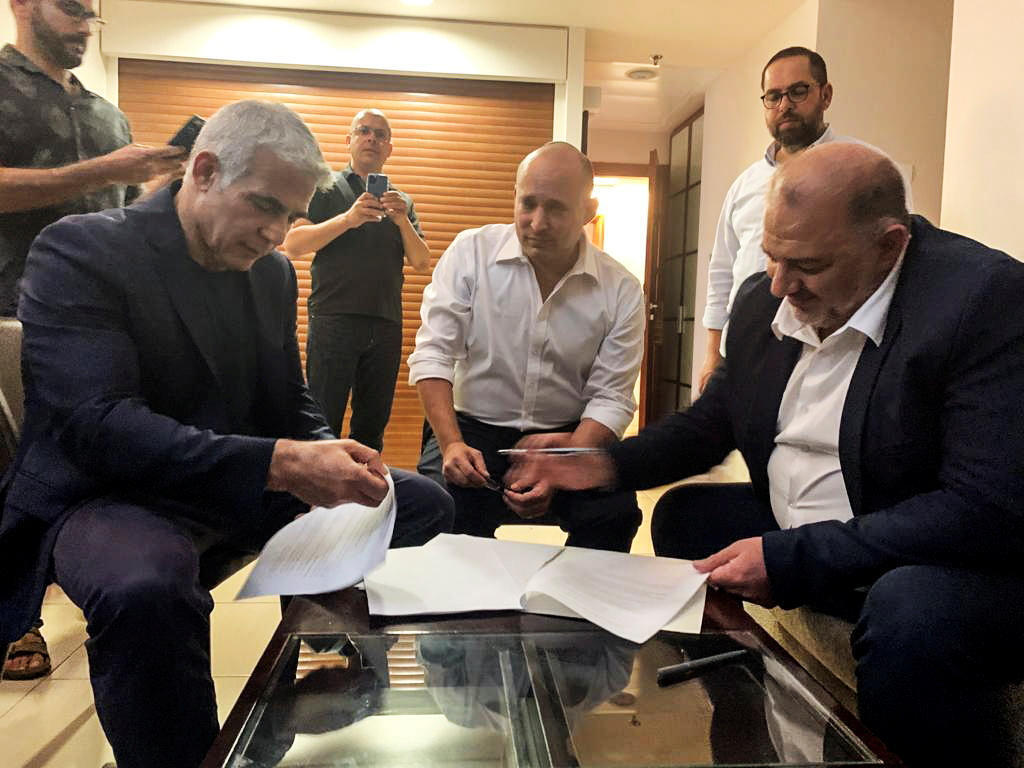

4 View gallery

Mansour Abbas, left, with the heads of the other parties that make up Israel's patchwork coalition

(Photo: Ariel Zandberg)

Officials supporting the law, which first passed during the Second Intifada when Palestinian terrorists were blowing up Israeli buses and entertainment spots, say it is a matter of national security. Some also argue that it is necessary to preserve the Jewish demographic advantage in Israel.

Interior Minister Ayelet Shaked has said she would reintroduce the legislation, which expired at midnight on Tuesday, next week.

Meanwhile, it is unlikely that any of the Palestinian spouses who have requested permanent residency in Israel will obtain it in the near future, since Shaked can reject requests on an individual basis and has said she would do so until the legislation is renewed.

Abbas, 47, a married father of three who was born and still lives in the predominantly Druze town of Maghar in the Galilee, is an unlikely choice to join an Israeli government.

Abbas studied to be a dentist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and has a license to practice dentistry.

During those years, he was the head of the Arab Students’ Committee and a follower of Sheikh Abdullah Nimar Darwish, the founder of the Islamic Movement in Israel. He became a leader in the Islamic Movement, eventually being named deputy chairman of its moderate Southern Branch.

4 View gallery

Mansour Abbas clasps hands with Prime Minister Naftali Bennett during the Knesset session to approve their new coalition government, June 13, 2021

(Photo: AP)

He is, according to his biography on the Knesset website, the formulator and author of the Islamic Movement Charter, which reinforces Wasatiya Islam, defined as moderation or a “middle way.”

Upon graduation, Abbas briefly practiced dentistry, a profession he reportedly pursued to please his parents, but kept circling back to his activism on behalf of the Islamic Movement, and politics.

Abbas founded his United Arab List Party ahead of the 1996 elections and it has run in all subsequent elections either as part of electoral alliances or, in the last election, on its own. He is, according to his biography, studying at the University of Haifa for a master’s degree in political science.

The left-wing daily Haaretz reported that as a leader of Arab students at Hebrew University, Abbas sought to achieve the students’ rights by negotiating directly with the university administration instead of waging an ideological battle.

His decision to support Israel’s 36th Government is a continuation of this mindset, according to Haaretz: “He had branded himself as the authentic representative of the common people, marking the secular elites as irrelevant, and has adopted a pragmatic approach that has spawned a utilitarian agenda – all at the expense of national issues and questions of identity.”

The newspaper calls Abbas “an intellectual with broad horizons and a man of letters who occasionally sounds a note of religious fanaticism. He has met with some of the people most hostile to Israel but doesn’t hesitate to deliver a speech against a backdrop of the country’s flag and symbols. He’s a wizard of compromises and political alliances who’s capable of aborting those ties in an instant and turning his back on his associates.”

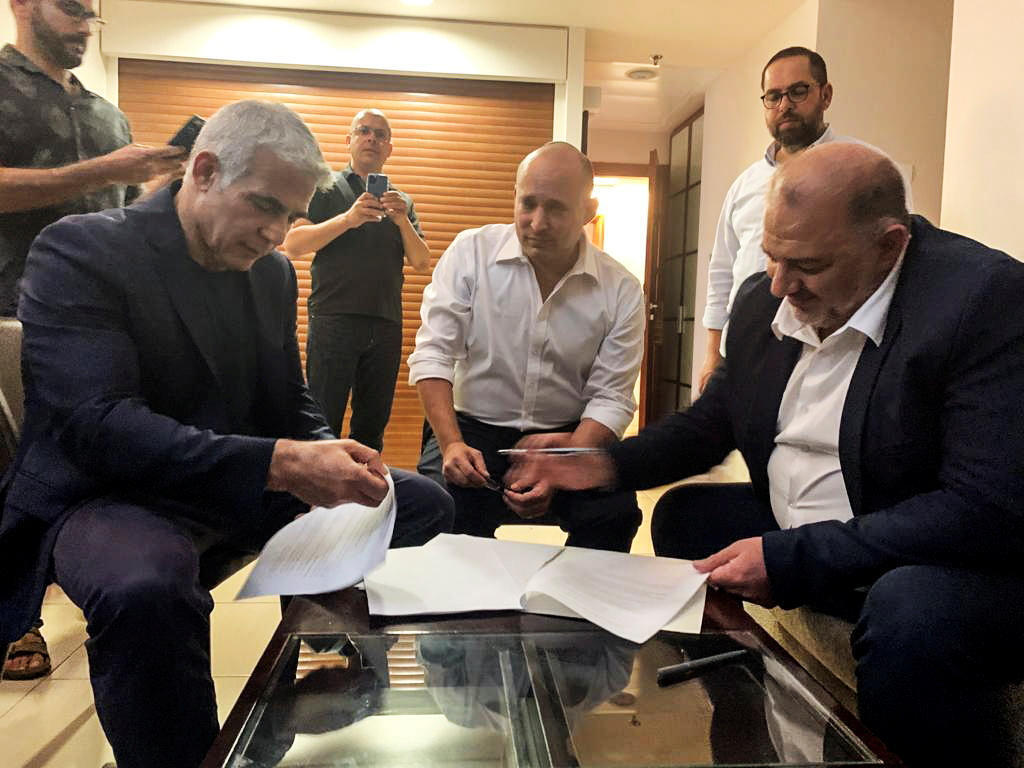

4 View gallery

Yair Lapid, left, Naftali Bennett, center, and Mansour Abbas sign their historic coalition agreement, June 3, 2021

(Photo: Reuters/United Arab List-Ra'am)

But Sami Abu Shehadeh, a Knesset member for the Joint List, the coalition of predominantly Arab parties that included Ra’am until the most recent election, wrote in a recent op-ed that: “People like Abbas are part of the past. Palestinians in the streets, bolstered by global campaigns of solidarity, have shown that we are much stronger than many expected. … Any pragmatic political engagement between Palestinians and Jewish Israelis should be based on the fundamental principles of equality, freedom, justice and security for all.”

In recent months, Abbas has alternately called for an end to the occupation of Palestinian territories that he says is turning Israel into an apartheid state and said, in an address in Hebrew, that “what we have in common is greater than what divides us,” and that “now is the time for change.”

That change started on Monday with the deal he worked out on the Citizenship Law.