Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Four months ago, during a research trip to Iraq as part of her research work at Princeton University, Israeli national Elizabeth Tsurkov was abducted by the Shia militia group Kataib Hezbollah.

Read more:

This was not her first time in Iraq, as she had previously been there four years ago investigating Kurdish communities in Iraq and Syria. In a comprehensive article published in July 2019 in Ynetnews’ sister publication Yedioth Ahronoth, she described the horrors in Iraq under Islamic State control, the hardships of life in Mosul after its liberation and her own concerns about the militias. Read Elizabeth Tsurkov's article in full.

15 View gallery

Elizabeth Tsurkov's original article, published July 2019

(Photo: Yedioth Ahronoth Archive)

A city that became a symbol of the fight against ISIS

"The most severe restrictions were imposed on women, the most vulnerable segment of the population," Samira tells me. We talked in Mosul, her hometown. She is a young, cheerful woman, sometimes removing her hijab without hesitation, showing a lack of concern for immediately putting it back on. She confidently interacts with men and gazes into their eyes, behavior not typical for an Iraqi woman.

At the age of 23, Samira is a mother of two daughters born to Alaa, a fallen ISIS fighter. "He forced me to carry them in my womb," she recounts, anger flickering in her large eyes as she reveals her relief at discovering her husband was killed in battle.

Her brother was captured by ISIS, and in order to release him, her other brothers forced her to marry a fighter from the organization who pursued her. "They took us as sex slaves, just as they did to our Yazidi and Christian sisters," she says. "They were captured as Sabaya (referring to non-Muslim women who were enslaved and used as concubines), while we were turned into Sabaya through marriage. Everything was done by force, we couldn't escape, they violated us like they violated the captives."

Nearly two years have passed since Mosul was liberated from ISIS control, but a visit to the city indicates that after the victory celebrations, the Iraqi government has almost disappeared from its streets.

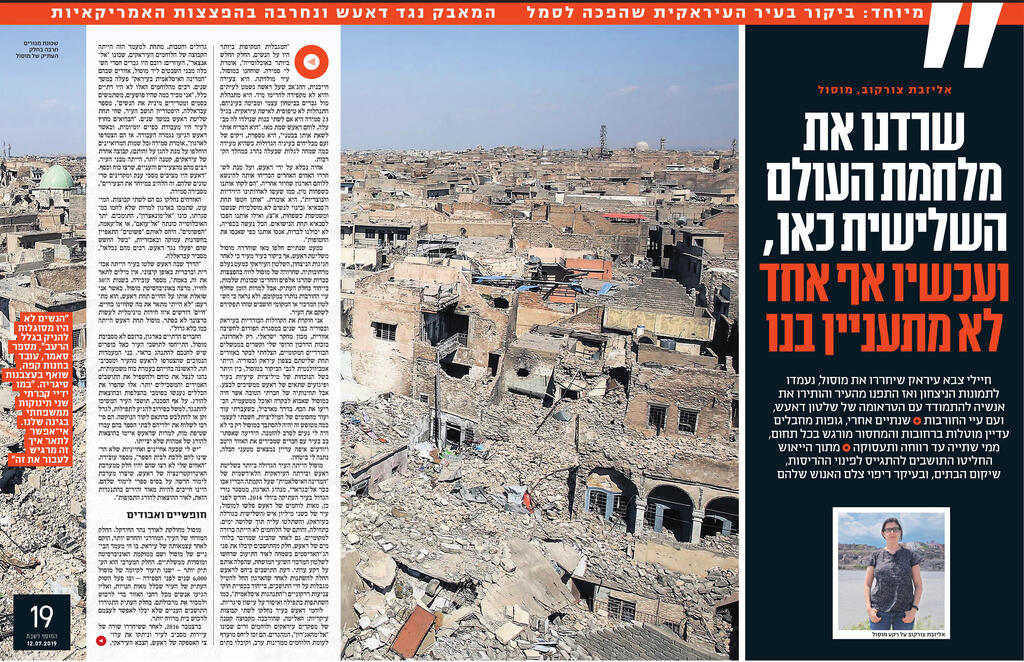

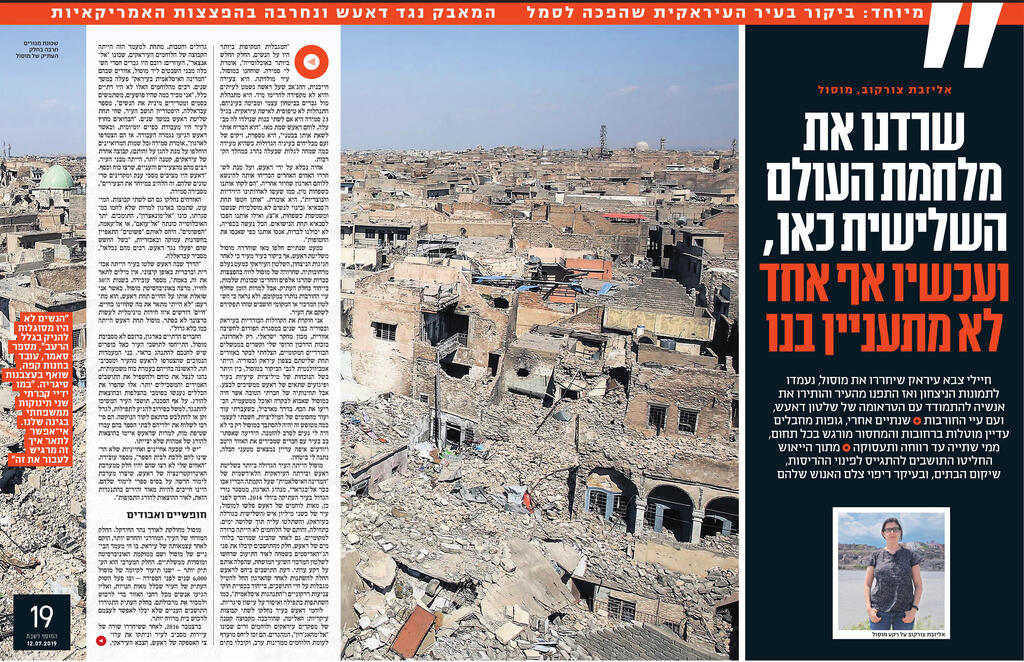

The liberation of Mosul was accompanied by heavy bombings that killed thousands and devastated entire neighborhoods, especially in the Old City. Despite the time that has passed, the ruins remain in place, and it does not seem that the central or local authorities believe it is their role to rebuild the city.

I have been researching Kurdish communities in Iraq and Syria for years as part of the Regional Thinking Forum, an Israeli research institute. Only recently, thanks to my Russian passport and connections with local Kurdish authorities, I managed to visit areas under their control in northern Iraq and Syria.

I had reservations about visiting Mosul, partly due to the presence of Shia militias in the city and ongoing attacks by ISIS cells. However, the heartfelt requests of my good friend who lives in Mosul, inviting me to visit her and taste her homemade dishes, tipped the scale.

As I passed through more and more checkpoints of the militias along the way, I thought to myself how foolish it'd be to get entangled in Mosul just because I didn't want to decline the invitation. However, the news that circulated in the city with friends who are familiar with the area and know where explosive devices are still located gave me a sense of security.

Mosul was the largest city under ISIS control and served as the unofficial Iraqi capital of the self-proclaimed "Islamic State." Its establishment was declared by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of the organization, from the historic Nuri Mosque in July 2014.

Just a month earlier, hundreds of ISIS fighters had infiltrated Mosul, a city of around two million people (the third largest in Iraq), and took control within three days.

Initially, the identity of the fighters was unclear to the locals. Even after realizing they were ISIS fighters, some residents welcomed them with joy due to their disgust for the corrupt central Shia authorities who had discriminated against them for sectarian reasons.

However, the perception of the residents toward ISIS began to change as the organization started imposing restrictions on their lives, particularly draconian modesty laws and “Islamic behavior,” such as mandatory participation in prayer and a ban on smoking cigarettes.

ISIS fighters in the city were divided into two main groups: the elite, comprised of a small group of Iraqi commanders and foreign fighters known as "Al-Muhajiroun," the emigrants. They received preferential treatment compared to Arab fighters and were allocated large houses and privileges.

Below them, there was the group of Iraqi fighters known as "Al-Ansar," the helpers: most of them were uneducated men from tribes near Mosul, areas where the "Islamic State in Iraq" had operated for years. Many of these fighters were not religious at all.

"I know some who were criminals, drug users and sexually harassed women," says Abdullah, a historian and resident of the city who lived under ISIS control for years.

"The Bedouins outside the city relied on daily manual labor, but when ISIS arrived, the work ended, so they joined the organization," says Samira (all names of the interviewees have been changed to protect their identities).

Another small group of Iraqis, mostly from the city itself, consisted of young and impoverished individuals seeking power and money. "ISIS would display giant screens and show their videos. It particularly attracted the young," explains Samira.

The civilians were also divided into two groups. The minority, who supported the organization despite not actively fighting for it, were called "Al-Munathirun," the sympathizers.

The rest of the population was referred to as "Al-Awam" or "Al-A'ama," the common people. Their treatment as "commoners" was characterized by deep suspicion and cruelty, "due to the fear that they would act against ISIS. Many of them were imprisoned," explains Abdullah.

"The way ISIS ruled the city was extremely cruel and barbaric. There are no words to describe it, really," says Obeida, a university lecturer in his 30s, when asked about life under ISIS. He becomes agitated when I inquire about life under ISIS, exclaiming, "I wouldn't describe what we experienced as 'life.' 'Life' requires some minimal freedom to do as you please openly. Mosul under ISIS was like a large prison."

The religious members of the organization, most of whom were not from Mosul, regarded the city's inhabitants as infidels who needed to be educated on proper behavior. Those from lower social classes who joined ISIS from the city and its surroundings, experiencing significant power for the first time in their lives, took advantage of their power to oppress the more wealthy steadfast and educated residents.

Those who violated the rules were publicly punished through flogging and execution. Despite the danger, the city's residents continued to resist, for example, by refusing to attend prayers, grow beards or dress according to the strict code. They refused to send their children to schools where they would undergo indoctrination, even though ISIS threatened to execute mothers who did not comply.

"I have seven nephews and nieces whom we didn't allow to go to school," Obeida shares. "My brothers didn't want them to be part of ISIS's indoctrination system, where they created a new educational system based on their textbooks. We had to be extremely careful in our resistance, given the frequent executions."

Liberated and lost

Mosul is divided along the Tigris River. The eastern part of the city, more modern and recently established, was built after Iraq's independence. It is home to the middle class of Mosul and houses the university and government institutions.

The western part is older, with evidence of Mosul's existence dating back to 6,000 BCE. It was the location of the city's ancient market, which included hundreds of shops and attracted people from all over the region to buy and sell their goods. The impoverished residents who couldn't afford more spacious homes resided in the old part.

In December 2016, after liberating a series of towns surrounding Mosul and severing ISIS supply routes, the Iraqi army, Kurdish Peshmerga forces and militias loyal to the Iraqi and Iranian governments launched an offensive to retake Mosul.

According to U.S. Department of Defense estimates, there were between 3,000 and 5,000 ISIS fighters in Mosul when the battle for liberation began. The forces advanced quickly and liberated the eastern part of the city in less than a month, while ISIS fighters and their families retreated to the west.

The liberation of western Mosul from ISIS required an additional seven months, despite the area being significantly smaller than the east. While the forces in the eastern part exercised relative caution, in the west, partly due to the difficulty of maneuvering through the narrow streets of the old city, the Americans and Iraqis relied on heavy bombardment before any ground assault. Approximately 10,000 civilians were killed in the battles to liberate the city, with a significant number of casualties resulting from coalition airstrikes and Iraqi army shelling.

Abdul Qadir, in his 50s, with prominent eyes and a tattered robe, shows me again and again his arm that was injured in an American airstrike, which also burned down his house. His skin healed but remains swollen and dark. He is unable to work in any job that requires the use of both hands and offers to show me medical documents that prove it, hoping that I can assist him.

"Misguided intelligence led to the bombing of houses where hundreds of civilians were hiding in basements. For example, in March 2017, an American airstrike on a building where two ISIS snipers were positioned killed 105 civilians who were seeking shelter in the basement"

Hassan, unemployed in his 30s, raises his voice as he tells me about the losses his family suffered during the battle for the city's liberation. "Twelve members of my family were killed in the bombings. We had nowhere to escape," he says with a trembling voice.

Misguided intelligence led to the bombing of houses where hundreds of civilians were hiding in basements. For example, in March 2017, an American airstrike on a building where two ISIS snipers were positioned killed 105 civilians who were seeking shelter in the basement.

Some of the civilians were killed by ISIS fighters, who used booby-trapped vehicles to demolish entire houses with their occupants. ISIS snipers targeted civilians attempting to flee from their controlled areas toward the Iraqi army. Other civilians were killed as a result of ISIS using them as human shields.

Only two out of the five bridges connecting the two sides of Mosul have been rebuilt, using makeshift structures that look like staples stuck onto the original structures. A city with over a million people is forced to rely on these bridges, creating terrifying traffic congestions near the river. The traffic jams discourage residents from eastern Mosul from visiting the western part, but there are also those who benefit from the situation.

Business owners in the east have more vibrant establishments than before. Along several streets near the Tigris River, residents flock to the small eateries that serve masgouf, the traditional Iraqi dish of giant grilled fish. During the long waits in traffic, one could smell, savor and even haggle over the prices.

'All the children were crying from hunger'

Since mid-2014, three-quarters of the city's residents have been uprooted. During the years of ISIS occupation, about half a million residents fled the city, and during the battles for its liberation, another million escaped.

According to UN estimates, approximately 400,000 people survived a seven-month siege on the historic part of the city. During my visit to Mosul, many residents of the old quarter wanted to talk about the horrors they experienced during the prolonged siege. They described, among other things, the severe hunger.

"When ISIS withdrew from the eastern part of the city, they took the food supplies with them," explains Mustafa, a man in his 30s who was born in Mosul. "When those supplies ran out, they raided the homes of civilians. They had their stomachs full while we had nothing." Prices skyrocketed under the siege.

"Women couldn't breastfeed due to hunger, and we couldn't find formula anywhere," says Samer, a 20-something coffee shop worker in the old city, his gel-slicked hair pushed back as he nervously puffs one cigarette after the other.

"I personally buried two infants from my family in our garden," he says, raising his hands, which appear too large in proportion to his body. His eyes well up as he adds, "We all need psychological help here. It's indescribable what it feels like to go through this. We survived the Third World War here in the old city, but now nobody cares about us. Instead, the budgets are going to places that haven't seen war at all."

After a moment of vulnerability, he quickly adds, "Women are the ones who need help the most, they are more affected by these things."

Others gathered around us also share stories of infants who died from hunger and family members killed by bombings, whom they were forced to bury in their own courtyards due to the danger of leaving their homes. Despite the immense hardship, there isn't even one center in western Mosul that provides psychological support to residents. "There's nothing here. All the centers are in the eastern part of the city, and it's difficult to reach them," says Samer.

Jamila, a resident of Mosul her 60s and the mother of my good friend who hosted me, describes how she and her family survived without supplies under the bombings.

"We were under siege for four months until we managed to escape toward the Iraqi soldiers. During the battles, there was relentless gunfire around us. Our whole family was stuck together in the house for 19 days, and we ran out of food and water. My son would sneak out every few days to try to find something," she says.

She points to her five-year-old granddaughter, with angelic face, green eyes and blond hair. "We had no way to feed her. All the children were crying from hunger." The family decided to escape and move to another house, and a few hours after they fled, their family home was bombed and completely destroyed.

In addition to the horrors of the siege, the city's residents had to deal with abuse from the Iraqi forces that liberated Mosul from ISIS. Men of fighting age, even if there was no evidence that they fought for ISIS, were arrested en masse and sometimes interrogated by the Iraqi forces who displayed sadistic pleasure as part of an attempt to force them to admit they fought.

Others - men, women, and children - were simply shot by the Iraqi army when they tried to draw water from the Tigris River or escape from the shelling. "The army believed that anyone who remained in the old city was ISIS. That's the perception held by many Iraqis to this day," says Abdullah.

'ISIS didn't appear suddenly'

Mosul is the capital of Nineveh Province, the most ethnically and religiously diverse province in Iraq. The province is home to Sunni Arabs, Christian Assyrians, Turkmen, Yazidis, Shia Shabaks and more.

Unfortunately for Nineveh, these groups, which are a minority in Iraq, do not receive preferential treatment from the central Shia-led government in Baghdad. Jamila, who lives with her extended family in a rented house in eastern Mosul, constantly complained during the lunch I had at her home. "Because we are Sunnis, they treat us like second-class citizens."

As she encouraged me to eat more and more of the stuffed vegetables she cooked, Jamila tried to convince me of how good it was during Saddam Hussein's era. "We used to live together here, Christians and Muslims, we would go to the market together, celebrate together, without any problems. Only people who were against something would get arrested. There was complete security, you could go to sleep without locking the door."

Her admiration for Saddam was so great that she and her husband named their son after him. Saddam, who is disabled from birth, now struggles to find work or assistance from charities, partly due to his name indicating his religious affiliation. "The Shia tell me, 'Go ask your Sunni friends in the Persian Gulf,'" he tells me at the family lunch.

Jamila is not the only one who misses the ruler who was ousted in 2003, and locals point to another factor contributing to the neglect of the city: the identification with Saddam Hussein's regime.

Neglect is evident in all aspects of life in Mosul: the security situation, the services provided to residents and the lack of investment in post-war reconstruction. Since the fall of Saddam, Mosul has suffered from a volatile security situation. The previous incarnation of ISIS, known as the Islamic State of Iraq, operated in the city for years, carrying out daily attacks and assassinations.

In order to fund their activities, its members extorted protection money from the local government and business owners, kidnapped residents for ransom, stole cars, conducted illicit real estate transactions, collected "taxes" on fuel smuggling and sold fuel and oil on the black market. These actions, along with threats from jihadists, led to the mass exodus of the city's Christian residents.

In a café in Arbil, over a cup of tea and berries covered in strange chocolate syrup, I met Joseph, an activist and poet from Hamdaniya, a Christian town near Mosul, who studied at Mosul University in the past.

"After Al-Qaeda's strengthening in Iraq, the residents of Hamdaniya demanded the establishment of a university in the town because traveling to Mosul became too dangerous," he says. Joseph himself was injured in an attack by the Islamic State of Iraq, which targeted a bus carrying Christian students in May 2010.

After the withdrawal of most American forces from Iraq in 2011, ISIS managed to infiltrate the local police and military forces and began collecting monthly "taxes" from the city's residents. "ISIS didn't appear suddenly; their takeover of the city was the culmination of 13 years of terror and jihadist activity," says Obeida.

The Iraqi security forces, dominated by Shia factions, did not prioritize the fight against jihadists. When ISIS invaded from Syria in mid-2014, thousands of Iraqi soldiers and police officers deserted, abandoning their weapons and fleeing to the south. They saw no reason to risk their lives defending areas far from their homes.

Today, despite the significant presence of the Iraqi army and Shia and local militias in the city, ISIS cells continue to operate in Mosul, carrying out attacks and kidnappings. Armed groups in the city, although ostensibly operating under the banner of the central government, often engage in violent clashes with each other.

Paralyzed in the face of destruction

Despite the widespread destruction in Nineveh, and despite nearly ten percent of Iraq's population living in the province, only one percent of Iraq's federal budget was allocated to Nineveh, around $120 million, while the reconstruction of Mosul alone requires between one to two billion dollars. However, even this measly budget was not properly utilized due to widespread corruption in the province, which is considered abnormal even by Iraqi standards.

The former governor of the province, Nawfal al-Sultan al-Akoub, was accused of embezzling public funds and granting lucrative contracts for debris clearance and city restoration, which were only partially implemented.

Politicians and local government officials intentionally delayed the implementation of projects by international aid organizations and local initiatives, demanding bribes in exchange for approvals to carry them out. Projects funded by the central government were purportedly completed in full, but the actual reality is completely different.

Throughout my visits to the Old City in the west, where prolonged battles against ISIS took place, the feeling was that the fighting had just ended. Whole buildings turned into piles of rubble, including in the Jewish neighborhood of the Old City. Other buildings appear as partially collapsed card towers. Those that remain standing are like naked skeletons - without doors, windows or contents. Everything has been looted and burned. In some of the buildings, the ground floor is inhabited, but the upper floors damaged by aerial assaults remain precarious, posing a threat to the occupants on the ground floor.

According to UN data, around 40,000 homes were destroyed during the fighting in Mosul. Immediate post-liberation research in the western part of the city showed that 78% of the buildings were significantly damaged. According to UN estimates, eight million tons of debris need to be cleared from Mosul, and at the current pace, it will take a decade to complete. The slow progress is partly due to the presence of numerous explosive devices left behind by ISIS.

Meanwhile, it appears that residents of the western part of the city have become accustomed to the destruction around them and are able to navigate through the rubble, some of which is marked with skulls and warnings of unexploded ordnance.

Despite complaints from the citizens of Nineveh and protests against Governor al-Akoub due to his close ties with the authorities in Baghdad, he managed to hold onto power. It was only in March 2019 that he was dismissed and faced an arrest warrant after a crowded ferry sank in the Tigris River, with occupancy more than four times its capacity, during the celebration of Mother's Day and the Kurdish New Year. Over 100 people, many of them women and children, drowned. The governor left, but not before his associates reportedly stole an additional $64 million in the final moments, according to the government's integrity committee.

After the liberation of the city, the residents of Nineveh expressed support for the central government, and it was the only province where the party of Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, a Shiite, who led the campaign against ISIS, emerged victorious. However, since then, these feelings have dissipated. "The residents have lost faith in the Iraqi government. The city is still in ruins, there is no real plan for reconstruction," explains Abdullah.

"The Iraqi government was only prepared for the battles to liberate Mosul, but not for dealing with a city that underwent heavy fighting, like Munich or Berlin after World War II," adds Obeida. "The scale of destruction here exceeds the capacity of any government, so they decided to rely on international organizations, but even they cannot rebuild such a large city."

Furthermore, Abdullah notes that the central government is not involved in the daily lives of the city. "Mosul is completely under the administrative, economic and military control of Shiite militias. No transactions can be conducted without their consent."

The presence of these militias is indeed prominent in the area. Although the residents of the city are not Shia, Shiite flags and symbols are displayed throughout the city. It seems that the residents have grown accustomed to the flags and do not see them as a threat, but they serve as a constant reminder that they are a minority under the control of the majority.

"There's no point in complaining about the flags. The local militias can't do anything. It's the Shiite militias who are in control," explains Samira as we pass by checkpoints adorned with flags.

All residents of Mosul suffer from a lack of job opportunities, a crumbling healthcare system, a shortage of schools, a lack of drinking water and only a few hours of electricity per day, but the situation is much worse in the western part of the city. In some parts of the west, there is no electricity or running water at all. Businesses have been destroyed and desperate residents in the area plead for job opportunities.

When I interviewed residents in the Old City, groups of men gathered around me, creating the impression that I work for an aid organization, and dozens wanted to sign up in hopes of participating in the city's reconstruction work. Many complained about having to register repeatedly, and in the end, the few who are employed in the reconstruction of the western part of the city mostly come from the east.

Running on Hope

In light of the negligence and corruption of the authorities, thousands of Mosul residents have taken it upon themselves to rebuild their city. Samira, who participated in a series of volunteer initiatives in the city and surrounding displaced camps, recounts, "There are now over 100 volunteer teams working day and night with minimal support, without receiving any salary. In return, we only get the opportunity to prove that we exist, that we love life and our city."

One of these initiatives involved the removal of over a thousand bodies, many of which belonged to ISIS fighters scattered throughout the western part of the city.

A resident of Mosul, Sarur al-Husseini, was disgusted to find that months after the city's liberation, the bodies continued to lie in the streets, decomposing and contaminating the drinking water. Residents' pleas to the municipality to remove the bodies fell on deaf ears. Sarur and her friends decided to start removing the bodies from the side streets and among the ruins, and the city's sanitation workers agreed to bury them in mass graves.

When the district head heard about the initiative, he issued an arrest warrant against Sarur, accusing her of supporting ISIS. Sarur was forced to suspend her activities for a while until it became clear that local security authorities refused to arrest her.

Other residents organized street cleaning days, while others cleared rubble from the Old City in a campaign organized on social media under the name "The Garbage Marathon." A group of students from Mosul University salvaged over 30,000 books from the university library, which had been bombed and set on fire during the conflict, in an effort to restore the magnificent library.

The city's residents have also rallied to assist one another in rebuilding their homes. Many have donated their money and time to help strangers renovate or rebuild their homes. The reconstruction of private homes, businesses, and public buildings is primarily carried out by private citizens and international organizations, such as the UN Development Fund.

Beneath the rubble, bodies of ISIS fighters and civilians killed in coalition bombings, as well as unexploded ordnances, can still be found. Fuad, a resident of the Old City, shares, "Recently, while rebuilding my own house, I discovered between 60 to 70 bodies beneath the debris." Even during the ferry disaster, due to the malfunctioning of rescue services, many civilians jumped into the water to save the drowning.

"Volunteerism is a sign of the times in Mosul today," says Obeida. "The work of volunteers strengthens solidarity with the impoverished and devastated areas. However, volunteers cannot rebuild bridges or undertake strategic projects. They cannot be a substitute for the government."

The trauma is still evident everywhere in Mosul. The war and its aftermath have left their mark on the city and its residents. The reign of terror by ISIS, the public executions under the bridges, mass arrests and torture, and the spies deployed by ISIS among the residents to ensure compliance have been replaced by a neglectful and failing government. And if all that is not enough, many in the central government and in Iraq view the people of Mosul as responsible for the rise of ISIS.

"The perception that Mosul supports ISIS has only grown since the liberation, even among intellectual circles. Many claim that the Shiite south came and liberated the Sunni north," says Abdullah. "It is our responsibility to prove that we were victims of ISIS, not accomplices to their crimes.”

He refers to recent concerts in the city and celebrations of various cultural festivals at Mosul University, saying, "That's why we celebrate the arts, our liberation. We play music openly after it was banned by ISIS. It is the best response to those who claim that Mosul was on their side."

"We need to ensure that this liberty continues to exist," says Abdullah. "The city's youth need to feel that their destiny is in their hands. This is what will prevent the next generation from joining ISIS."