The list of global conflicts seems interminable. Tensions in the South China Sea. Violence between Turkey and armed Kurdish groups. India and Pakistan. The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. And that’s just a sampling.

This year’s United Nations General Assembly opened on Sept. 14, and its annual high-level debate session is scheduled for next week, when leaders from around the world are afforded time on the global stage to discuss peace, opportunities and grievances.

7 View gallery

The flags of the United States, Israel, United Arab Emirates and Bahrain are projected on a section of the walls surrounding Jerusalem's Old City

(Photo: Reuters)

Many analysts have criticized the UN for doing just that: discussing – for days, weeks and years – without taking concrete actions leading to peace.

It is on that note that nearly 70 ambassadors to the UN gathered on Monday at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York to listen to a success story – one written nearly entirely outside of Turtle Bay.

Ambassadors from Israel, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco and the United States took the stage to recount the dramatic steps that led to the creation of the historic Abraham Accords normalization agreement, and each of their respective nations’ vision for further peace and cooperation.

Wednesday marks the one-year anniversary of the signing of the accords between Israel, the UAE and Bahrain on the White House lawn.

The sight of it all begs the question: What did the United Nations, often seemingly stuck in quicksand when it comes to solving difficult global conflicts, learn from large-scale Israeli-Arab/Muslim normalization, which only a short time ago was considered unthinkable?

7 View gallery

Israel’s Ambassador to the United Nationsm, Gilad Erdan, at an event to mark the first anniversary of the Abraham Accords at the Museum of Jewish Heritage

(Photo: The Media Line)

Which pieces of the template for fuller Middle East cooperation – economic benefits, uniting against a common enemy, leveraging cooperation with a global power, pooling limited resources – can be utilized by the UN in order to lessen disputes around the world? It’s a question to which apparently few have given much thought, even those who practice the art of conflict resolution.

“I would need to think about that,” said Mitch Fifield, the Australian ambassador to the UN.

“I’m not sure I have an answer to that particular question,” said Ukrainian ambassador Sergiy Kyslytsya.

Israel’s Ambassador to the United Nations, Gilad Erdan, speaks at an event to mark the first anniversary of the Abraham Accords at the Museum of Jewish Heritage, New York, where he is joined by, from left, Ambassador Lana Nusseibeh of the United Arab Emirates; Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield of the United States; Ambassador Omar Hilale of Morocco; and Jamal Al Rowaiei of Bahrain. (Mike Wagenheim/The Media Line)

7 View gallery

Two local residents of the UAE stand in front of a Hanukah Menorah in Dubai last December

(Photo: Chabad Org.)

In fact, the Foreign Affairs Ministry Spokesperson Lior Haiat said that he is not aware of a diplomat anywhere around the world who has reached out to his or her Israeli counterpart and sought counsel regarding the Abraham Accords.

“I don’t know of any similar dialogue, but one of those things I’ve learned in 20 years of diplomacy is that every conflict is different and trying to apply one solution to another problem doesn’t always work.

Every conflict has its own issues. In the last year we’ve reached a way to create a new reality – with others it might not be the way to solve their conflicts,” Haiat said.

“I’ll add that I don’t think a forced solution is ever a long-term solution. The international community doesn’t always know or take into consideration all the aspects of a particular conflict, and are often more interested in finding a quick solution,” he said. He added that the countries involved in the Abraham Accords knew their own circumstances best, and were able to find ways to move forward out of their own interests, rather than those of the UN.

We want to spread the word about this change in the Middle East. And the first thing we are asking from other countries is to support it, talk about it, about how important this change is for the stability of our own region, which has all kinds of positive global ramifications.

It seemed that most involved in Monday’s event felt that the spirit of the Abraham Accords should be used more as a feel-good story – an anything-is-possible inspiration – rather than as a blueprint for solving disputes.

“We thought it was important to just take a moment and mark these accords, because I think agreements like this need encouragement. And when governments get around the table and negotiate some of these really difficult issues, I think we find that progress can be made,” Lana Nusseibeh, the UAE’s ambassador to the UN, said.

“So, that’s what the accords mean to us, and I hope on the global stage at the UN, at the high-level week, we will see countries coming together to address the most difficult challenges the international community faces today,” she said.

Haiat added that the international community should look to the accords not only for the change they’ve brought about in the Middle East, but also how it positively affects other regions.

7 View gallery

The Moroccan, Israeli and U.S. flags fly from the cockpit of an El Al plane in Rabat after the first direct Israel-Morocco commercial flight

(Photo: AFP)

“This is what our diplomats do best: talk. We want to spread the word about this change in the Middle East. And the first thing we are asking from other countries is to support it, talk about it, about how important this change is for the stability of our own region, which has all kinds of positive global ramifications,” Haiat said.

Another consensus conclusion among those countries sharing the stage on Monday is that peace must come from within, rather than being foisted upon warring nations by the international community.

“First of all, these Abraham Accords agreements create momentum and it’s up to our leaders and our people to work on that and to build toward establishing peace, and also for bringing hopes and for making an end to all kinds of extremism and wars.

Our region has suffered a lot from the past wars. Now we need to work for a very warm peace – peace of heart, peace of mind.

And that the next generation of our region deserves to live together – all the people – in peace, cooperation, harmony and prosperity,” Omar Hilale, Morocco’s ambassador to the UN, said.

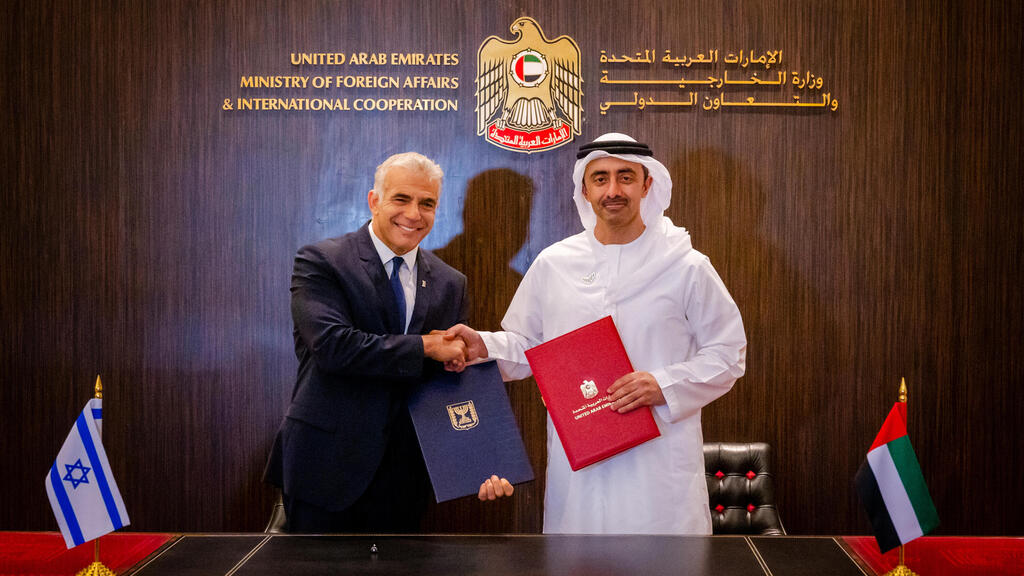

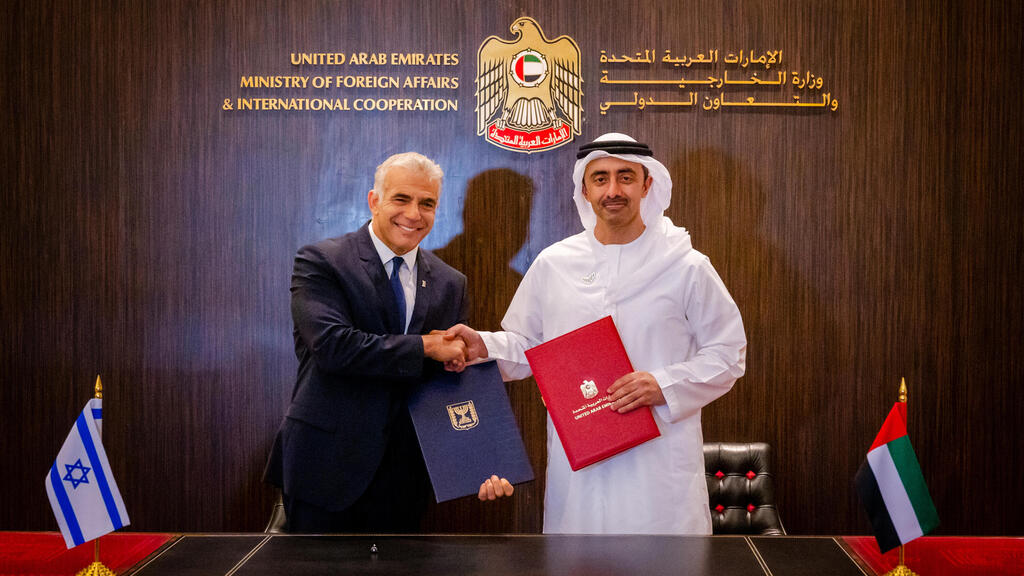

7 View gallery

Foreign Minister Yair Lapid meeting with his Emirati counterpart Abdullah bin Zayed al-Nahyan

(Photo: EPA / Emirates News Agency)

In fact, Israel, which has often faced immense pressure from the UN to make policy changes to bring about solutions to conflicts with its neighbors, noted that one only need to look at the Abraham Accords to realize that it’s best when bodies like the UN just stay out of the equation altogether.

“I think that other nations around the world can learn that the only way to move forward is by a process of reconciliation between the two peoples. You cannot come from the outside and force a decision upon any nation.

So, any intervention of the UN is unnecessary. It won’t help. It’s counterproductive. Mainly, that’s what the UN does,” Gilad Erdan, Israel’s ambassador to the UN and U.S., said.

“Here, you have the perfect example of how our nations … we built it bottom up. Our relationships, we started to encourage and work with each other and that made it easier for the leadership to make the right decisions.

And even the previous [U.S.] administration, the UN administration, together with the Biden administration, they helped us to nurture and to work together.

7 View gallery

Then-prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, United Arab Emirates Foreign Minister Abdullah bin Zayed al-Nahyan, and Bahrain Foreign Minister Khalid bin Ahmed Al Khalifa, during the Abraham Accords signing ceremony

(Photo: EPA)

They didn’t try, thankfully, to force anything upon one of us. And these are also my expectations for the UN, for the secretary-general and for all member states: Don’t try to force anything on Israel,” said Erdan.

U.S. Ambassador to the UN Linda Thomas-Greenfield sounded a hopeful message at Monday’s event, that the Abraham Accords model could be used to good effect elsewhere.

“I am determined to explore how we can translate these agreements into progress within the UN system. Events like this point us in that right direction,” she said from the podium.

But, seemingly much like the majority of those in attendance, little thought has been given thus far, one year after a groundbreaking agreement changed the face of one of the most conflict-ridden regions in the world, to the lessons it can impart to the rest of the world.

Article written by Mike Wagenheim and republished with permission from The Media Line