Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

In the lands of Arabia, where Jews used to live, a tenacious explorer can – here and there – find remnants of a people swept away on the sands of time and political tensions.

Here in Sanaa lie the ruins of a synagogue, there in Cairo sit the cracked graves of a Jewish cemetery, bearing witness to the vibrant communities that once existed in happy harmony with their Muslim friends and neighbors.

That all changed in 1948 with the creation of the State of Israel, regarded by its Arab neighbors as an interloper in the Muslim world, an unwelcome usurper whose establishment led to the displacement of the Palestinians who lived there. These Arab nations and their inhabitants now viewed their once respected Jewish communities with antipathy, blaming them for Israel’s creation and accusing them of loyalty to the nascent Jewish state over their homeland.

The animosity morphed into persecution on a national and personal level – leaving the Jews of the Arab world with little choice but to flee. Some went to Israel, some found the sanctuary they sought in Europe or North America; almost all left almost everything behind, to be picked over those who had for so long welcomed them but then cruelly turned their backs.

And yet while the Palestinian refugees were embraced by the world, an international wall of silence surrounded the plight of the Jews forced out of the nations they had called home for centuries. This silence has eroded in recent years, but their stories remained little-known, little-shared and of little interest in the world.

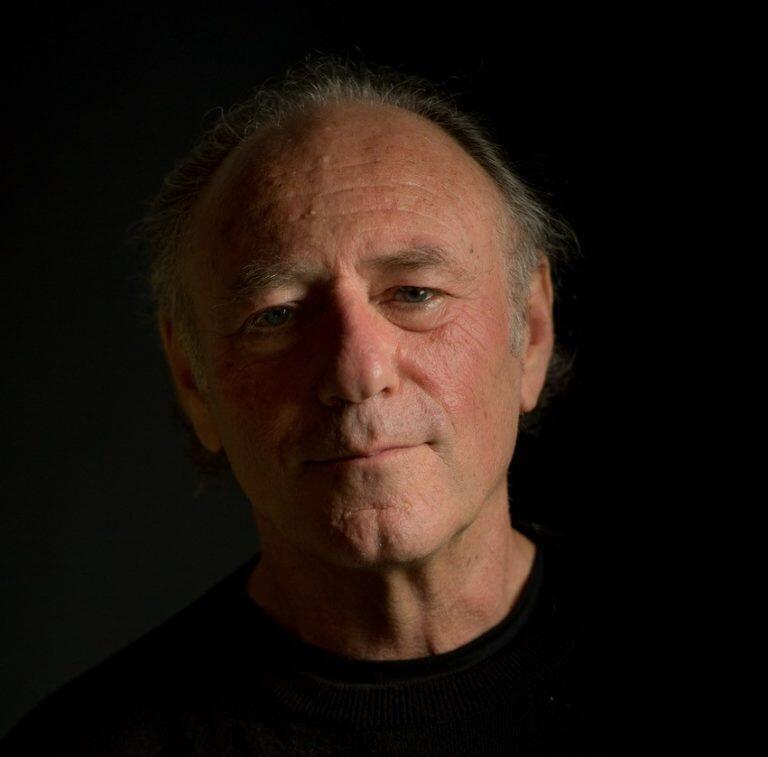

Slowly this is changing. A new book titled “Sephardi Voices: The Untold Expulsion of Jews from Arab Lands,” by Henry Green and Richard Stursberg, seeks to bring these stories to even greater prominence, telling the events of this recent chapter of Middle Eastern and Jewish history through the eyes of those who lived it.

Green acknowledges the oddity of a Canadian Ashkenazi Jew (himself) and a Catholic (Stursberg) writing the story of the Sephardi Jews, but says it was ignorance of their plight that motivated him.

“The Sephardi Jews’ history ended for me in 1492,” Green admits, referring to the expulsion of Jews from Spain after centuries of persecution.

But arriving in Israel in the 1970s, Green was drawn to a social rights movement called the Black Panthers, thinking it was the same movement as in the US, from which its members had in fact taken their name.

“I got introduced to this other incredible population that makes up Israel [about] which I had no idea,” he tells The Media Line.

“It was so strange to me. They introduced me to a different culture, to a different food and music. I felt that I was kept from a secret that was very beautiful,” he says.

Green became the first person to write in English about the programs that then-Prime Minister Golda Meir was implementing in order to help integrate Sephardi Jews into Israeli society.

As the director of Jewish Studies at the University of Miami, Green delved deeper into the subject – developing and expanding his research, culminating in the Sephardi Voices project that unites the history of the million or so Jews who once resided between the Atlantic Ocean and the Tigris River, but whose presence was near gone in a single generation.

“I realized that the stories of all these people who were displaced were never heard and they needed a voice,” Green says.

Green does not apportion blame for the lack of public awareness about this other tragic chapter of contemporary Jewish history, but only seeks to understand and explain how this happened.

“Israel in the first generation was just trying to survive, there was not resources,” he says. “America did not supply military aid ‘til 1968; they were not supplying economic aid. Israel depended on the Diaspora to survive.

“They needed immigrants, but when they brought them, they had no resources. They did not speak Hebrew; they spoke Arabic, Ladino, or other languages, while the Jews that came from the Holocaust [Europe] were speaking German.”

Furthermore, he says, “the Europeans had more education.” They had the skills needed by the newborn, besieged state to consolidate and expand. And surrounded by enemies as it was, what began as expediency for a desperate nation became what Green calls “institutional discrimination.” In the newly created State of Israel, the Ashkenazi Jews were the elite and their Sephardi brethren seen as of a lower class.

“The people who could help build the country would go to the urban areas, and the ones who did not understand what was going on, would go to the more rural areas because Israel needed to develop it,” Green explains.

Making matters worse, he says, was the trepidation towards those who looked and talked like the enemies of Israel who had sworn themselves to its destruction.

“The people who came in from the European world, they looked white. But the ones who were coming from the Arab world, they look Semitic, and they spoke Arabic,” he tells The Media Line. “From a security issue, you did not know who was who, and this created another kind of fear.”

5 View gallery

Jewish immigrants from Iraq at Lod Airport near Tel Aviv, 1951

(Photo: Israeli Government Press Office)

Green stresses that while the stories of the Jews of the Middle East and North Africa are similar in shape and form, individual experiences were distinct. Jews from across the region found themselves persecuted to varying degrees, in varying styles and with varying timeframes.

“The Middle East and North Africa is not monolithic,” he says. “Generally speaking, their rights are taken away over time in different ways.”

He cites the example of Iraq, which joined Egypt, Syria, Lebanon and Jordan in declaring war on Israel in the immediate aftermath of its birth in 1948, in what Jews around the world call the War of Independence.

“Iraq took the position that the Jews were detrimental for the country so they denationalized them, took away their property, they killed various Jews and made their life unbearable,” Green says.

“The Israeli government also did covert operations to increase the fear of the Jews there because they needed olim [immigrants to Israel]. That combination led the 150,000 Iraqis to leave between 1950-1951.”

Green is referring to bombings that targeted the Jews of Baghdad in those years. Some have attributed these attacks to Israel as an incentive for Jews to emigrate to the country, although Jerusalem has consistently denied involvement. The bombings directly preceded an Israeli operation to airlift the Jews of Iraq. Known as Operation Ezra and Nehemiah, the action saw around 130,000 Iraqi Jews taken to Israel via Iran and Cyprus.

As recent in history as this chapter is, many of those who fled are still alive, and can vividly recall their lives before their displacement.

One such person who appears in Green and Stursberg’s book is British philanthropist David Dangoor. Born in 1948, he lived with his family in Baghdad until his father Sir Naim Dangoor took them to the UK in 1959. His family can trace its venerable Iraqi lineage back centuries, but that did not save them from the oppression that followed the creation of the State of Israel.

“Dad had records relating to at least eight generations, going back to Nissim Dangoor born circa 1700,” David Dangoor tells The Media Line. His father, a renowned businessman in his native land and the second-oldest man to ever receive a knighthood in the UK, was the grandson of Baghdad Chief Rabbi Hakham Ezra Reuben Dangoor and the son of Eliahou Dangoor, who at one time was the world’s foremost printer of books in Arabic.

“Dad took us out in 1959 but tried to continue with his businesses ‘til he found it impossible in 1963, when he lost his nationality and all his businesses and assets” to the Iraqi government, says David.

Dangoor, who today lives in London, says he bears no animosity towards the people of Iraq, acknowledging their own troubled history and suffering.

“I feel goodwill to the Iraqi people and an aspiration that they find peace and stability, and recognize their former Jewish citizens by recognizing Israel, where the vast majority of them now live,” he says.

According to Dangoor, “many Iraqi people – especially the more educated and Western leaning ones – regularly express very nostalgic feelings about the Jews that they feel were lost to Iraq.”

In fact, he says that a video on YouTube about his family and the larger Jewish community having to leave Iraq “had nearly 20,000 viewings with many warm and positive comments in Arabic from Iraqis.”

One of the comments on the Arabic-language version of the video, posted by someone calling himself Dr. Salam Hussein Ewaid even reads: “Greetings, my love and my respect, you are an authentic and loyal Iraqi.”

The rights to the 69-minute film, called “Remembering Baghdad,” have now been acquired by Netflix for a five-year period in Europe.

To David, aspects of Iraqi culture still persist in his life, and those qualities he has passed on to the younger generations: “The importance of family, community and tradition.”

In Egypt as well, Jews felt the blow of national hatred towards Israel as soon as the state came into being, seeing their rights stripped away. Yet as bad as it was, Henry Green says, things got substantially worse when Gamal Nasser took the presidency in 1956, four years after he played a decisive role in overthrowing the last king, Faruk I.

“Everything changed,” Green tells The Media Line.

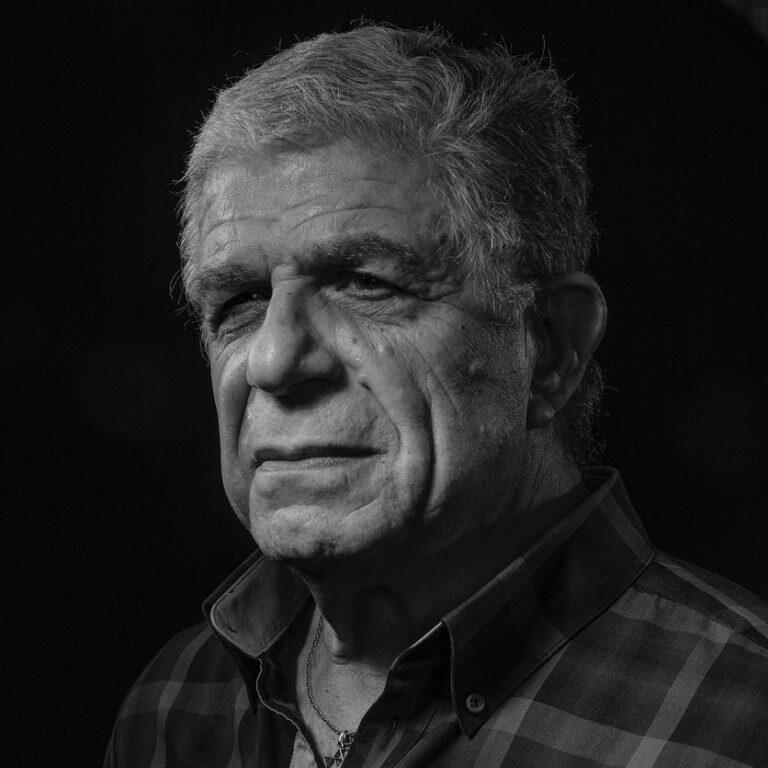

David Shama was born in Cairo in 1945 and grew up in Alexandria, where he says his family was part of the elite and very Westernized. But again, that elevated status did not save the Shamas from persecution – and it is something that stings even today.

“I have no great love for Egypt or Egyptians,” he says.

“We were part of the Egyptian environment, and my father was a successful businessman,” Shama tells The Media Line. “He knew a lot of people and a lot of people knew him, yet when he was arrested and accused of being a spy for Israel and England, nobody came to his aid; no one. [Not the] people that he helped, loaned money to whenever they needed and gave money to whenever they needed. It was brutal to be completely betrayed like that.”

Shama describes the treatment they received in those years in the most severe terms.

“Leaving the country we felt very much betrayed,” he says. “We were raped out of everything we owned. My father was imprisoned as a British and Israeli spy, he was tortured while my mother, my sister and I were captive in our home in Alexandria under house arrest. It was a very brutal, emotional situation.”

David Shama now lives in Canada, where after retiring from his children’s clothing firm he began a dog care company, but his distaste for Egypt and the Egyptian people still lingers.

“I believe it was a situation where the masses jumped on board” with targeting the Jews, he says. “They really had no reason to do what they did. I mean, look, there are people who get themselves into trouble here and there, but to paint the whole Jewish people with the same brush is wrong.”

When the 1967 Six-Day War began with the invasion of Israel by Egypt along with Jordan and Syria, it only brought back the terrifying memories of his childhood.

“I had seen what my father went through, I had seen as a young boy what I endured being on the street,” he says. “On many occasions walking on the street, going somewhere with my nanny or whatever, they would empty these urine [containers] over us, which was absolutely disgusting.”

Even the peace agreement between Israel and Egypt in 1979, which still holds to this day, did not lessen Shama’s animosity: “I don’t think that peace was done because the Egyptians wanted peace… it was more, they really had no alternative.”

According to Shama, the lack of awareness of the story of the Jews of the Middle East and North Africa has many culprits.

“Many people don’t know it because frankly there was no publicity about it,” he says. “It was a situation where Jews are being corralled like animals, and basically nobody cared, and the Jews kept silent.”

He says that unlike the attention given to the Holocaust, “we didn’t get the support from the media that we would have needed in order to get this thing out so that the world would know what was happening.”

The fact that it is becoming more discussed today is a good thing, he believes, for it is “very important that the young generation understand what happened.” This is especially the case, Shama says, given the current vilification of Israel.

“All these young people who are continuously in universities blacklisting the State of Israel as an apartheid state, is because they just have no education, nor do they want to have an education about the subject.”

Green attributes some indifference to the fate of the Jews of the region to the tumultuous state of the planet in the immediate aftermath of World War II.

“The UN did acknowledge that there were two refugee populations,” he says, but geopolitics inevitably played its part.

“When Israel was founded, there were about 70-80 nations. Eleven [of them] were Arab nations and with the Cold War going on, there was a sense that one had to deal with the Arab displaced population,” he says.

“In terms of the world, what happened was that the attention was not on Israel between 1948 and 1967. Europe had been devastated during World War II. It was not on anyone’s radar.”

Unlike Dangoor and Shama, Beirut-born Edy Cohen Halala only left his country of birth in 1990 at the age of 17, decades after the creation of the state where he now lives. But like them, his family could trace its roots back for generations and its departure was triggered by antisemitism.

“We were in what is Lebanon for at least 120 years,” Halala tells The Media Line. “We spoke Arabic at home. I was raised in an Arab country, I went to an Arab school, I spoke Arabic with my friends and neighbors.”

Halala grew up in a country ravaged by a bloody internecine conflict.

“The Lebanese civil war began in ‘75 till ‘91. So almost all my years in Lebanon, I saw the country destroying itself with a civil war,” he says. “I didn’t see the Lebanon of before the civil war, I didn’t live in Lebanon during the time when it was called the Switzerland of the Middle East.”

Even so, the family remained until the rise of the Iranian-backed Shiite militia Hizbullah, now one of the most powerful political entities in Lebanon, which set its sights on his own father.

“The Jewish community had suffered from antisemitism, and in 1985 Hizbullah began to kidnap Jews, among them my father. They killed 11 Lebanese Jews [including his father], and this is the moment that we felt that we must go. You cannot stay in a country where you are persecuted,” he tells The Media Line.

Even so, the memories of his childhood remain, tinged with regret that visiting the nation of his birth is out of reach due to its persisting conflict with Israel.

“You cannot forget the country that you were born in and lived in for almost 18 years,” Halala says. “I still have the memories, friends, my mother tongue, so as you can never forget your mother, neither [can you forget] your maternal language. Unfortunately, there is war between Lebanon and Israel and I cannot go.”

He says that without Hizbullah, Lebanon would be a very different place.

“The Lebanese problem will not resolve until the full demilitarization of this terrorist organization,” he maintains. “Lebanon would still be dangerous for Jews.”

Halala sums up the story of the region’s Jews after the creation of the State of Israel succinctly:

“The million Jews living in the Arab lands are gone,” he says. “This is ethnic cleansing. Being Jewish in a Muslim country was impossible during the 20th century.”

He does not recoil, however, from being described as an Arab Jew, unlike some who were born in – and were forced to flee from – Arab countries.

“We are not Muslims, but we are Jews with Arab origins,” Halala says. “There are people that do not like this term, but I feel comfortable with it because this is the truth, in my point of view.”

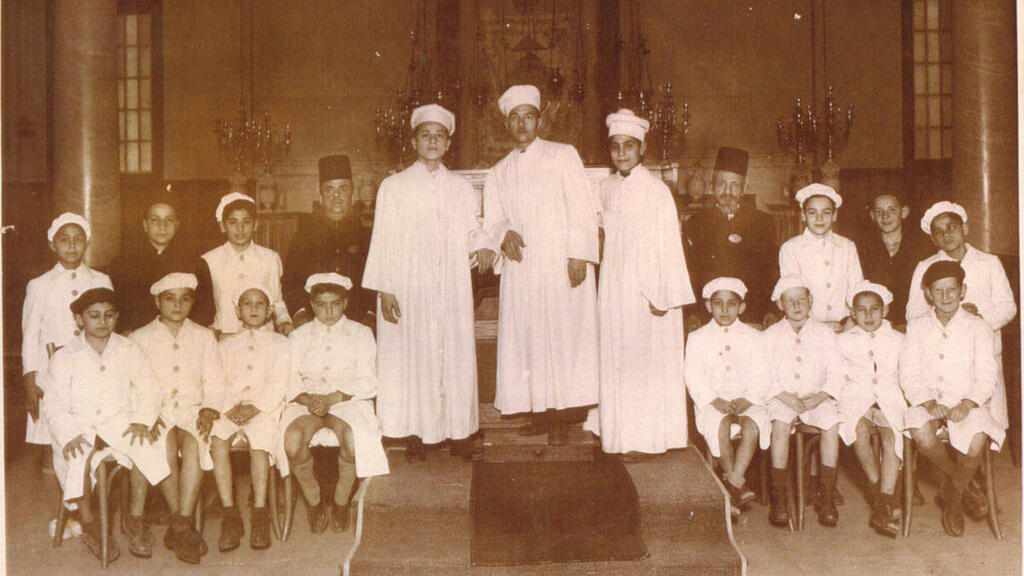

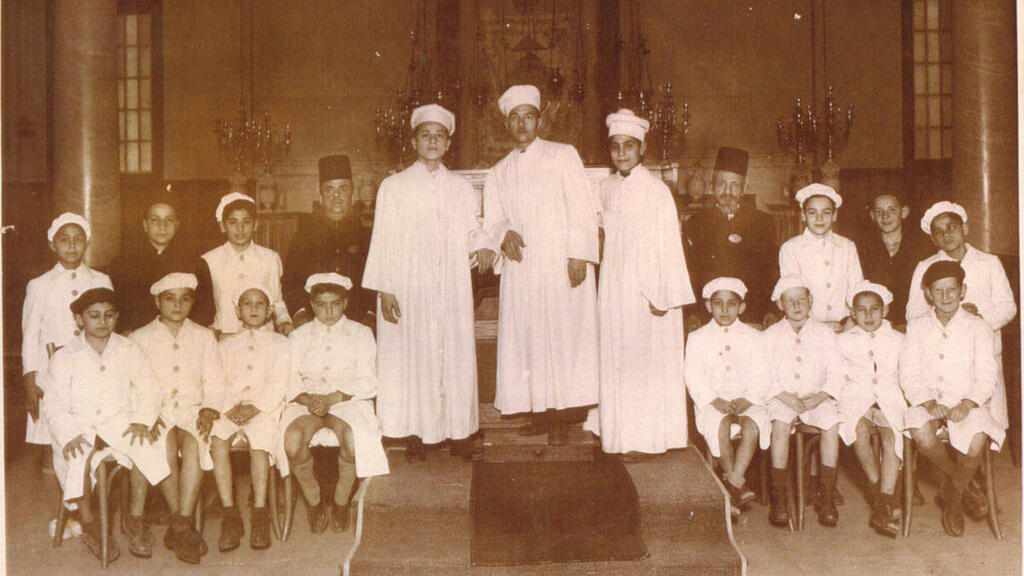

5 View gallery

The Jewish choir of Rabbi Moshe Cohen at Samuel Menashe Synagogue in Alexandria, Egypt; date unknown

(Photo: Nebi Daniel Association Public Photo Collection)

Green says that the experiences of the Jews of Arab lands have begun to resurface in the past two decades as people have become more eager to celebrate where they and their families came from.

“In the last 20 years, things have changed in terms of identity politics; now you get strength from bringing your identity,” he says. “With that has come an acknowledgement that these cultures are very nourishing and need to be supported.”

This is more the case in Israel than the Diaspora, he says, which is still dominated by its “Ashkenazi majority.”

“The Sephardi [Jews] made up 15% of Israel in 1948; today they comprise between 55-60% of the country, so the demographics have changed. Today Sephardi food and music are part of the Israeli culture. In Israel, it is not about a melting pot anymore, but more about multicultural identity.”

Where almost a million Jews once lived and thrived across the region, today – in the most optimistic of estimates – there are just 23,000. According to Green and Stursberg, the total amount of assets left behind, including businesses, houses, farms and bank accounts – are worth in today’s money more than 100 billion USD, roughly the size of the economies of Yemen, Iraq and Tunisia combined. None of the states from which Jews were driven have provided any reparations.

With his book, Green says, he is trying to allow others to undergo the same enlightenment that he experienced back in Israel in the 1970s, when he stumbled across a movement of Sephardi Jews fighting for their rights.

“The book is trying to say: ‘wake up!’ There is another story here, and that story is about victimization but also a story about resilience. A story of people making new lives in Israel and the Diaspora.”

The story was written by Sara Miller and Debbie Mohnblatt and reprinted with permission from The Media Line