When Yischar Zalmanovitch was promoted to corporal, he spoke to his grandfather. "Grandpa, you wanted me to be a rabbi? Now I'm corporal," Yischar told him.

In Hebrew, corporal is pronounced "Rav-Turai." Rav is also the Hebrew word for "rabbi." That's how he summarizes the conflict between the religious world he came from and his IDF service.

The 21-year-old is the head of new media in the IDF Haredi administration, a unit dedicated to integrating ultra-orthodox youth into the army, and is also in charge of establishing policy and guidelines for their recruitment.

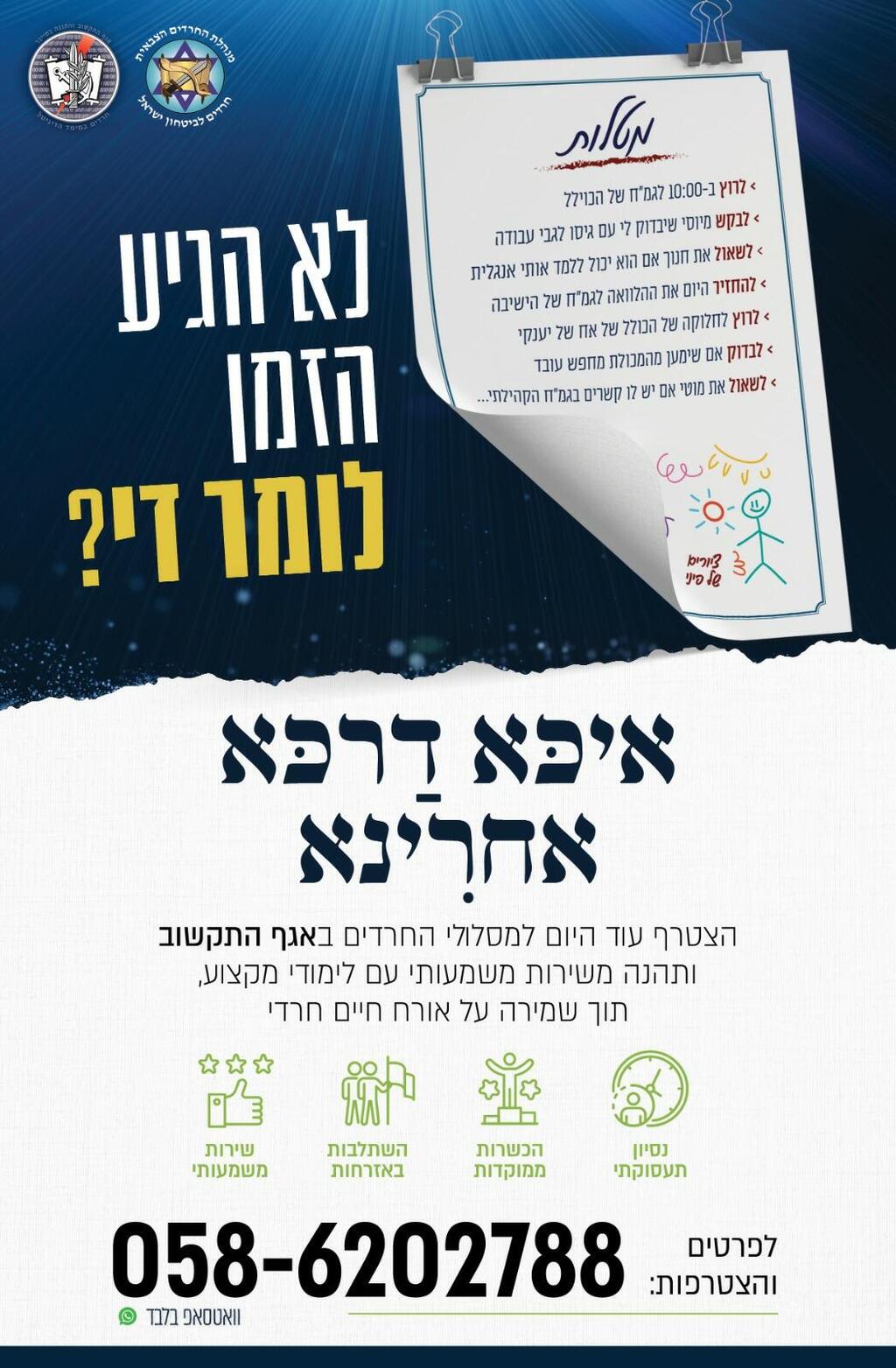

His military service revolves around convincing other religious Jewish youths to enlist, by utilizing videos showcasing the nature of service in ultra-Orthodox units.

"We do everything involving digital content and advertising to promote the IDF to the Haredi youth," says Zalmanovitch, who is often featured in the videos, speaking in a light, humorous tone.

"Familiarity with a prospective recruit is often tricky, since he has no idea about military hierarchy, and his ideological background doesn't revolve around military service. That's the baggage he brings with him when deciding whether to enlist or not."

Many of the ultra-Orthodox have no smartphones or internet access. How do you breach that gap?

"Marketing the IDF to the Haredi community is the most difficult thing there is, so we start by addressing their concerns. Their Internet comes across in WhatsApp and Facebook groups - where their identities retain anonymity.

"There's no profile picture or username. Not even a fictional one. There will be no pictures in the feed or story. For all we know, it's your average yeshiva student hiding in some store room, googling 'Haredi in uniform.' That's where we come in. We want his corresponding results to be positive. That way he can see what the IDF can offer him."

The firstborn of six, Yischar studied in a yeshiva. But, early childhood pictures show him wearing the IDF uniform. "My uniform back then said 'soldier in the army of God,' complete with a beret and rank. As you can see, I'm standing tall and I think my officer would approve.

"I was born into a Hassidic family so my path to the yeshiva was preordained, but I frequently found myself on the outs with the traditional path. I felt I could contribute in a way that doesn't necessarily align with the world I came from.

"During my yeshiva studies in Netanya, everything was organized. You wake up, do morning prayer, study Torah until 13:00pm, break for lunch, have more studies, break for dinner, then more studies, and then, go to sleep. That's your day," he says.

"You arrive at your dormitory at the yeshiva on Saturday evening and you don't return home until the following Friday, straight on to the bus that takes you there," he says. "After a while, I became depressed because I felt I was suffocating. That's how I understood I wasn't meant for the traditional path."

While his parents were opposed to him leaving the yeshiva, they managed to stay on good terms. "I never felt any conflict with religion, only with the specific path I was on. The rigid structure that allowed nothing but studying the Torah, wasn't suitable for me, and I even purchased a non-Kosher phone, which exposed me to the media scene."

His journalistic path began in a Haredi service, through which many ultra-Orthodox receive their news. "I wrote to them on their WhatsApp group, saying I wanted to work there. The job paid NIS 500 ($148) a month working 12 hours a day. I started as an interview coordinator, a sort of researcher if you will.

"I used to call former prime ministers like Ehud Olmert and Ehud Barak and convinced them this was the avenue for them to communicate with the ultra-Orthodox. Later on, I became a broadcaster."

Shy of his 18th birthday, he began working on the Haredi website JDN and was a Knesset correspondent for "Yomleyom" - a newspaper for observant Sephardic Jews. At 19, he became the political correspondent for the Kol BaRama Haredi Israeli radio station, eventually appearing as a panelist for the Knesset Channel as well as the right-wing Channel 20 (currently known as Channel 14).

"Leaving the yeshiva was accompanied by a lot of familial arguments because in Haredi circles it's pretty black and white. You're either studying the Torah or you're a bad child. When I began receiving positive feedback on my work in media, I understood my talent lies elsewhere.

"When people wanted to interview me, I sat in front of the mirror pondering what had happened to that yeshiva kid who cried in the bathroom, and now people want to interview me."

Still, getting acquainted with Israeli society meant bridging many gaps. Spending hours on YouTube, he learned about Israeli heads of state, wars, and even TV. "It was step-by-step. Every election campaign was an opportunity to learn more. The more I learned, the more I realized how much I still have to learn."

At 20, he pulled the breaks on all of that and enlisted in the IDF. "I realized how meaningful it is to serve in the IDF to get the full Israeli experience. Plus, there was a small contingent of Haredi youth who were following me, so I felt I needed to be a role model."

He was even accepted to Army Radio, but gave up his spot. "It became clear that once I give up on that, my service would revolve around Haredi youth. My commander and I agreed on establishing this social media structure that would involve all ultra-Orthodox IDF units, advertising to the Haredi audience in any way we could."

He conveyed his decision to someone of major rabbinical authority, Rabbi Tzvi Elimelech Halberstam. "I was afraid he would disapprove, but he was rather inquisitive and said he hoped I would be able to help every Haredi soldier to maintain his lifestyle and contribute as much as possible."

Do you sense a change in Haredi society when it comes to the military service?

"They've become more pragmatic about it. It's not always as well-known as the opinions of those on the fringe, who loudly oppose the service, but it's there. Haredi leadership understands the shortage of options for those ejected from yeshivas, and the IDF meets that need. All rabbinical authorities are in touch with those in the IDF who are in charge of recruitment in order to facilitate the proper transition."

Do you cooperate with Haredi media?

"The IDF Spokesperson's Unit has already engaged Haredi media. I can't definitively say it has reached the upper echelon, but we try to initiate change wherever the opportunity arises."

Alongside videos that illustrate the process of enlisting and the nature of service, Zalmanovitch also produces "lighter" content. "We write down the script and then go and start filming. Sometimes we post on Instagram, and sometimes TikTok , depending on the subject.

"When a Haredi teen sees a video about rabbis speaking to soldiers and accompanying them through their service, along with stories from infantry troops, he gets a different perspective. We speak their language. If we have to make clips in Yiddish to get to more recruitment prospects, we'll do those too."

Ads that he posts emphasize the path a soldier takes, combining service with Torah studies and receiving training required to integrate into the Israeli job market, all while maintaining the Haredi lifestyle. It comes across as inclusive and inviting, making a prospective recruit's decision an easier pill to swallow.

There are still many Haredim who denounce this, calling those who enlist pejorative names. Does it pain you to see it?

"Ultimately, what we're selling is not easy to swallow in the ultra-Orthodox world, so it gets frustrating. You wake up and see comments aimed against you. On a personal level, it sometimes pains me to see it.

"Most often I encounter ignorance. Some are amazed to learn that they would not be forced to remove their sideburns when they enlist. Personally, no one in the IDF has ever told me to change anything about my appearance."

Another obstacle for Haredi recruits is often the family cutting contact with them, loneliness, financial difficulties, and ridicule. While Yischar himself is doing okay on that front, he's aware of the reality for others.

"The IDF is adept at handling these issues. If a soldier needs accommodations made in order to make things easier, he receives them."

What about soldiers whose parents cut off all contact? Some are thrown out of their homes.

"The Netzach Yehuda foundation helps with that, including housing for Haredi soldiers in consideration of their lifestyle, including gender separation and Shabbat dinners. There's a brotherhood here and we help each other. No one falls through the cracks, even with the most complex issues."

While often met with hostility in Haredi circles, the smartphone is never far away from Yischar. It's his main work tool. Still, he always makes time for yeshiva studies. "I am learning more about the Torah now than I did when I was in yeshiva full-time," he says.

"Overall, it's a long, difficult process. You walk a fine line between not appearing disengaged from the Torah and introducing Haredi youth to something different. It's all about cooperation, not coercion. The Haredi public is one big family, and word travels. I was the first to enlist, but little by little, more and more joined the IDF in various roles, which normalizes it in the community."

What's your objective when you wake up in the morning?

"Primarily, it's to make service appear more approachable and less foreign. I also don't want an ultra-Orthodox father sitting shiva for his son, because he enlisted. He needs to understand that the IDF will take care of his child."