Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

In some ways, Itamar Ben-Gvir would seem an unlikely kingmaker in Israel’s upcoming election.

By his own count, the far-right provocateur and ultranationalist member of the Knesset, Israel’s parliament, has been charged with crimes more than 50 times and convicted in eight cases, including once for providing support to a terrorist organization. After trying three times since 2019, he squeaked into the Knesset last year, when then-Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said he was unfit to serve as a minister. Months later, Ben-Gvir played a notable role in the leadup to Israel’s deadly conflict with Hamas.

Yet Ben-Gvir appears virtually assured of remaining part of Israel’s government after the upcoming Nov. 1 election, not just as a rank-and-file member of Knesset but as a senior minister — overtaking other right-wing politicians in influence and with Netanyahu directly contributing to his meteoric rise.

In a powerful indicator of Ben-Gvir’s mainstreaming, he was invited to participate last week in a mock debate held by Blich High School in Ramat Gan, a prestigious secular school famous for its role in hosting political candidates. His appearance there inflamed a nationwide debate about democracy and freedom of speech — and a screaming match between dueling protesters outside the school’s gates that required the intervention of dozens of police officers.

“Fascists, racists, you are enabling Hamas and Hezbollah. You want Israel to be a religious state, just like Iran and Saudi Arabia,” shouted one left-wing activist at the predominantly young religious boys and men holding signs in support of Ben-Gvir.

“Death to terrorists. Left-wing traitors, terror supporters. You don’t belong here, go home,” a far-right activist shouted back. Some chanted “May your village burn down,” a racist soccer hooligans’ slogan usually directed at Arabs.

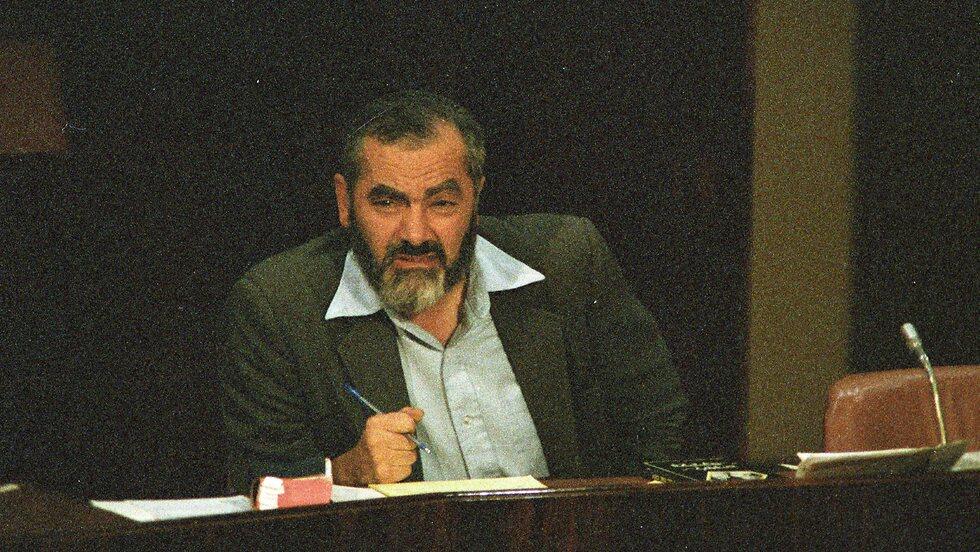

8 View gallery

Itamar Ben Gvir in 2010 detained by police after shouting slogans at White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel during his visit to Jerusalem

(Photo: AP)

The ascendance of Ben-Gvir and the far-right party he represents — Otzma Yehudit, Hebrew for Jewish Power — is among the most notable aspects of the upcoming election, Israel’s fifth in three years. A protégé of Meir Kahane, the American-Israeli Jewish extremist-turned-politician who advocated for openly racist policies, Ben-Gvir was once shunned by political parties and by the media for his extremist positions, racist ideology and violent activity. He has gone from outcast to the in crowd in just a handful of years: Netanyahu, who understands that his political comeback depends on uniting Israel’s right, hosted Ben-Gvir and Religious Zionism party leader Bezalel Smotrich at his home in Caesarea last month.

Afterwards, they announced that they would all work together to ensure that the right wing prevails in November. Ben-Gvir and Smotrich combined their parties into one slate, which is now expected to win 12 or 13 seats of the Knesset’s 120. On Tuesday, Smotrich predicted that Ben-Gvir would wield great influence in the next government.

“According to the polling numbers, as of now, Itamar will certainly be a senior minister,” Smotrich said. “This is the meaning of democracy.”

The dynamic has observers straining to identify precedents. When else, anywhere, has an openly and proudly racist candidate with a criminal record of supporting a terrorist group seized so much influence?

“I’ve been trying to think of analogies and I think David Duke is one who comes to mind,” said Natan Sachs, an Israeli-American who directs the Center for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution, referring to the racist and antisemitic leader of the Ku Klux Klan in the United States who unsuccessfully ran for governor in Louisiana in 1991.

“But he’s going to win a seat which David Duke never did, and he’s being pushed to do so and facilitated very openly and very personally by the former prime minister and the current head of the opposition,” he added. “This is a watershed moment for Israel.”

The situation would have been hard to imagine three decades ago, when Ben-Gvir vaulted into public awareness after he was interviewed on national TV holding an emblem he had broken off of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin’s car amid protests against Rabin’s willingness to concede land to the Palestinians. “Just like we got to this emblem, we can get to him too,” Ben-Gvir said.

Although he wasn’t implicated in Rabin’s assassination three weeks later, Ben Gvir, only 19 at the time, became the face of the incitement that led to it. Since then, he has made a name for himself by pushing for the ideas that animated Rabin’s killer. He has called for deporting Arabs who aren’t loyal to Israel, annexing the West Bank and exercising full Israeli sovereignty over the Temple Mount, where the Al-Aqsa mosque is located.

As a lawyer, he has represented right-wing Jewish extremists. As an activist, he has showed up in sites of terror attacks, calling for collective punishment against the Palestinians. And as a member of Knesset, Ben-Gvir used his position to open a “field office” in the hotspot of Sheikh Jarrah during the 2022 flareup in the neighborhood, and led thousands in a “march of the flags,” waving Israeli flags through the city’s Muslim Quarter. In December, he landed in the news after pulling a gun on Arab security guards during a conflict over a parking spot.

Political opponents and liberal pundits commonly accuse him of being a “pyromaniac” roaming Israel’s combustible friction points with a metaphoric oil can in hand.

“Ben Gvir is incredibly dangerous, both himself personally — he has a long list of indictments — and for the movement he represents, as the modern incarnation of the Meir Kahane,” said Rabbi Jill Jacobs, the American CEO of the rabbinic human rights group T’ruah, who has called for a crackdown by U.S. authorities on donations to groups tied to Ben-Gvir and others like him.

For his supporters, many of them from the haredi Orthodox sector, Ben-Gvir’s identification with Kahane is often a boon. Like Kahane and Ben-Gvir, they envision an Israel that is centered exclusively on Jewish interests. They are also increasingly involved in politics beyond their immediate communities.

“The haredim became much more right-wing in the past 30 years, undergoing what we call ‘Israelization’ — quite the opposite from their traditional anti-Zionist ideology and support of left-wing governments,” said Dani Filc, a political scientist at Ben Gurion University. “And that’s why many haredim are now voting for Ben-Gvir.”

Before coming to Israel, Kahane was the leader of the militant Jewish Defense League in New York City, and he served time in prison both in the United States and Israel. As an activist and then a political candidate, Kahane called for expelling Arabs from Israel, banning intermarriages between Jews and Arabs, segregating Jews and Arabs, and revoking Israeli citizenship for non-Jews. His Kach party had a history of harassing Israeli Arabs.

After Kahane was elected to the Knesset in 1984, despite widespread opposition, the other legislators — including Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, a conservative, responded by walking out of the parliament en masse whenever he rose to speak. American Jewish groups also frequently spoke out against him. A coalition of left- and right-wing lawmakers teamed up to pass a law that barred him from running for reelection in 1988. He was assassinated by an Egyptian-American fundamentalist at a hotel in New York two years later.

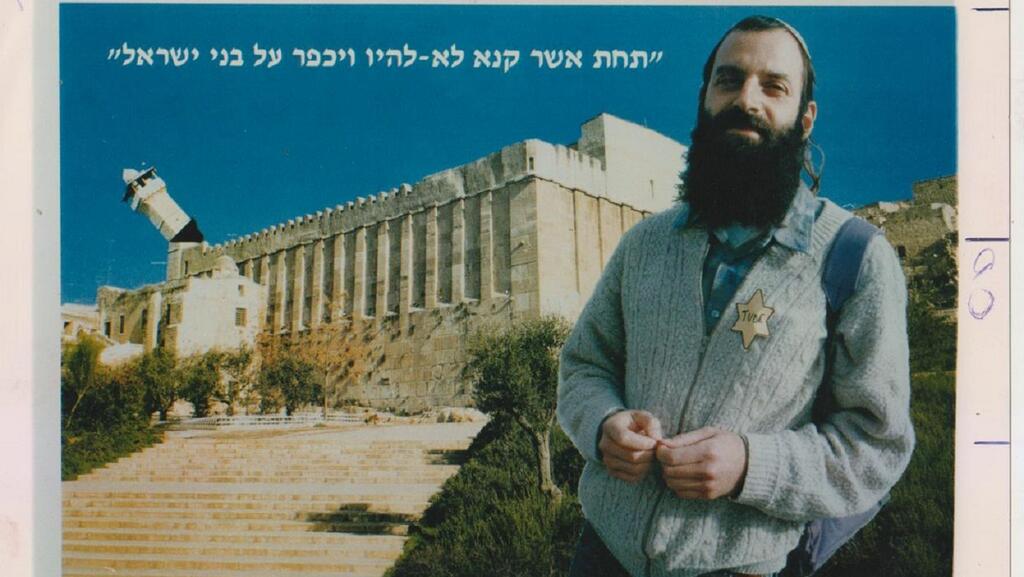

8 View gallery

Meir Kahane stands in the center of a Jewish Defense League protest in Washington, March 1977

(Photo: AP)

Ben-Gvir, who grew up in a traditional Mizrahi family in Jerusalem, is a proud disciple of Kahane, a foot soldier since his teen years when he was radicalized by his opposition to the Oslo Accords between Israel and the Palestinians, brokered by Rabin. He studied at a yeshiva founded by Kahane, handing out flyers and passing on Kahane’s racist credo to the younger generation as head of his youth outreach arm.

While Ben-Gvir now says he disagrees with some of Kahane’s views, such as segregating Jews and Arabs, he still calls him a “hero.”

Yet Ben-Gvir is experiencing little of the rejection his mentor faced. Unlike Kahane, Ben-Gvir became an accepted part of the Israeli right wing and is currently among the politicians covered most in Israeli mainstream media.

Ben-Gvir’s anticipated electoral success reflects the rightward shift Israeli society has been experiencing for decades. A recent poll by Israel Democracy Institute revealed that a record-high 62% of Israelis place themselves on the right wing of the political map.

As Israelis have moved to the right, the nature of the nationalist camp has changed dramatically as well, according to Filc.

“Menachem Begin [Israel’s sixth prime minister and the founder of Likud, Netanyahu’s party] was a mix of inclusionary populism and more traditional liberal conservatism. But today you have three kinds of right-wing. The first is politicians like [current and interim Prime Minister] Yair Lapid, a progessive neo-liberalist, whose economic policies are clearly right-wing. The second kind is Likud, which is right-wing populism similar to the far-right parties in Europe,” Filc said. “The third kind is more extreme — the religious zionists, with people like Ben-Gvir.”

His speech at Blich High School’s mock election panel could provide an explanation for Ben-Gvir’s growing appeal among Israeli voters. Contrary to his mentor Kahane, who never yielded to public outrage and refused to soften his racist message, Ben-Gvir is well versed in the art of adjusting to an audience.

In front of a hall full of secular teenage high school students, many of them liberal and hardly any of them extremists, Ben-Gvir dialed down much of his rhetoric. Though he had opposed gay pride marches in Israel, he told the students that LGBTQ Israelis “are my brothers.” On relations with Arab citizens of Israel, Ben-Gvir wrapped his call for expulsion and for tough punishments with a message of coexistence based on loyalty.

“I have no problem with Arabs. I don’t advocate death to Arabs, God forbid, or expelling all the Arabs. Anyone who’s loyal, who wants to live here, ahlan wa sahlan,” he said, using the Arabic words for “welcome.” “But I do have a problem with anyone who throws Molotov cocktails at us.”

The normalization of Ben-Gvir, said Nadav Eyal, a political commentator on Israel’s Channel 13 news and a columnist for Yediot Aharonot newspaper, is a result of both political necessity and the media dynamics that reward provocation.

“Netanyahu made him a legitimate part of the right-wing bloc by inviting him to meetings and talking to him,” Eyal said. “And at the same time the media is bombarding Israelis [with Ben-Gvir]. He’s getting much more than his fair share of airtime compared to other politicians, including very senior ministers. And I think that’s bad editing. It’s sensationalism.”

Eyal noted that in the second election in Israel in 2019, Ben-Gvir didn’t cross the electoral threshold to enter the Knesset but was among the top three politicians in airtime.

“I really think that’s a problem,” Eyal said. “He’s very talented in his relations with the media. He’s considered a reliable source for journalists, and he always comes to the studios when he’s invited. He knows how the news cycle works better than probably any politician in Israel today.”

By now, Ben-Gvir’s political clout is a given, as is the legitimacy he has earned among mainstream Likud leaders, who view him as not only a possible coalition partner, but as a coveted prize that could pave their way to victory in Israel’s political stalemate.

In the public square, however, his presence still provokes heated emotions. Haim Shadmi, a prominent left-wing activist who demonstrated against him outside Blich High School, said Ben-Gvir’s status as a member of Knesset should not cause him to be accepted in normal discourse.

“The Nazis were elected democratically too. And when they came to power, they changed the laws,” Shadmi said. “Israel is in a similar situation to 1930’s Germany, becoming more fascist and racist. And Ben-Gvir is the ultimate symbol of this.”

On the other side of the street, 22-year-old Adir Busani was waving an Israeli flag in a small camp set up by Ben-Gvir’s party.

“For years, the school invited left-wing politicians and Arab-Israeli parties to participate in these kinds of events. Now they want to silence Ben-Gvir. They want to silence us for supporting him. But we won’t allow that to happen. He loves his country, and we support him,” said Busani.

Inside the school, Ben-Gvir was challenged by a student who questioned why he should listen to someone who called Baruch Goldstein — a Jewish extremist who killed 29 Palestinians in Hebron in 1994 — his “hero.” A TV interview in 2016 filmed at Ben-Gvir’s house in Hebron famously showed that he had a picture of Goldstein on the wall.

Ben-Gvir admitted to Goldstein being his hero when he was 17, but that he changed his mind since then. “I don’t think Goldstein is a hero,” he said. “And I don’t think we should kill Arabs, or need to deport Arabs.”

In the last year, as his star has risen, Ben-Gvir has distanced himself from the “Death to Arabs” chant he and his followers long used. He has also spoken about left-wing Israelis, a shrinking group, in more tolerant terms than in the past.

For his critics, the fact that Ben-Gvir is tempering his message is less a relief than a cause for grave concern.

“Ben-Gvir is smart about it. He tries to portray a slightly softer image,” said Sachs. “But while he may put on a responsible face for a while, it certainly makes everything more dangerous [to have him in the government] … And with normalization, I’m worried that it’s going to take a very long time to put the genie back in the bottle.”