This month marks 21 years since the night when a Palestinian from the neighboring village emptied a whole magazine into the children's room, killing three, including a five-year-old, and then killed the mother. Aviv Kochavi was among the first to arrive in the settlement of Itamar, at the Shabo family's home.

More stories:

The bodies were carried onto the road, one by one, in front of his eyes and the father's eyes. In the exchange of fire, the commander of the settlement's security unit was also killed, and the house went up in flames as the battle subsided.

The next day, Kochavi, then the commander of the Paratroopers Brigade, entered to capture Nablus.

Ynet sat down for an interview with the outgoing IDF chief to discuss the impact of the traumatic Second Intifada period on Israeli society and gain insight into his perspective on the future.

Fresh out of the top job in the military, he refuses to discuss politics. He plans to return to his hobby of painting, but concludes meetings every night around 11pm. "I turn my attention to the business world related to new technologies, as well as the fields of education and social activism," he says. "I made two decisions: first, to thoroughly explore the realm of possibilities and not rush into making a decision. The second decision is that I do not intend to engage in the field of defense. There are many other topics that interest me."

Five months into his vacation, Operation Shield and Arrow breaks out, and Kochavi is following the unfolding events from the comfort of his room instead of in the IDF headquarters.

The army assassinates the leaders of the Islamic Jihad, with children also getting killed, more than 1,400 rockets fired into Israel. Koachvi is in the backseat seat, no longer on the gas and brake pedals or on the throttle. He keeps himself updated with the news, careful not to pry into reports from his friends in the army or offer advice, leaving the stage to the new chief of staff.

He admits that the feeling is very strange. "I am taken back to the summer of 2002, to the long battle with the terrorist who barricaded himself in the children's rooms. I've been in terrorist attack scenes, faced tough situations in Lebanon, but this was different, horrifying,” he says.

“You witness a massacre, and the next day you go out again to capture Nablus with a sense of righteous path. We captured Nablus seven times, and honestly, I cannot deny the intensity of satisfaction and personal fulfillment.”

Dithering orders

In the first year and a half of the Second Intifada, Kochavi stood out among the young officers who pressed the chief of staff to capture Palestinian cities but the orders they received were confusing.

10 View gallery

Kochavi with then-IDF chief Shaul Mofaz in the Balata refugee camp during Operation Protective Shield

(Photo: IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

"One night, we operated in Balata with a Paratroopers' reconnaissance unit. The force sneaked with several auxiliary units, and we were already on the outskirts of the target, engaging in a highly sophisticated operation designed to target terrorists,” he says.

“As a brigade commander, I receive a call from the head of the Planning Directorate [Giora] Eiland, and he tells me, 'Listen, Aviv, can you explain to me exactly what your operation is about because I can't understand it.' I describe the operation to him. He replies, 'Listen, you have to stop it because General Zinni, the American mediator, is landing in an hour, and if we have five or ten Palestinian casualties on the night of his arrival, it greatly complicates the talks.

Of course, I asked him to call off the order through the conventional channels. Shortly after, we received instructions to withdraw. During that period, we had to be very creative and find ways to achieve maximum success in the war against terror while allowing the diplomatic process to proceed. For example, we developed a method to initiate activities that would provoke the enemy, lure them out toward us, and cause them harm without crossing the established boundaries."

The cycle of violence spiraled, and after another six months of dithering orders and bloody suicide bombing attacks on Israeli civilians, Kochavi finally received approval to capture the Balata refugee camp, which was regarded by the IDF as a burial ground, a place where rivers of blood will flow through the some of the world’s narrowest alleyways.

"On the day of the operation, at six in the evening, I received a message that the mission was not approved. An hour later, I received a message that it was approved, but we could only enter one corner of the camp. Two hours later, there was a different directive, and afterward, I received permission to enter, but one of the corners of the camp, adjacent to the city of Nablus, was not approved for closure," he says. "This event also reflects the dilemmas and concerns that existed both at the diplomatic and military levels. The war's objectives set by the political level were still limited."

"The moment the Supreme Court, led by Aharon Barak, determined that the State of Israel is in an ongoing armed conflict with the Palestinians and that it is not a matter of policing activity, it was a watershed moment from which all references to counterterrorism methods changed completely, not only for us and the court but also for the international community, partly due to the high regard the Supreme Court holds in the eyes of the world"

When given the green light, Kochavi gathered the brigade's officers in al-Ras, which overlooks the refugee camp. They had 48 hours to prepare. Murky intelligence warned of alleys that could become death traps for IDF soldiers, but it provided only information for arrests and assassinations, not tactics for urban combat. The initial discussion yielded no breakthrough.

"For the first time in 20 years, we were required to occupy a densely populated urban area. Since the First Lebanon War, we fought in open territories, primarily in the [South Lebanon] Security Zone," he said.

"Had we consulted the principles of urban warfare, we would find that the first rule is to avoid entering built-up areas and to bypass them. But if we do enter, the doctrine dictates using controlled fire into the streets and houses to prevent the enemy from taking positions on rooftops and in windows. We understood that if we did that, we might defeat terror, but it would result in hundreds of Palestinian civilian casualties. It would also contradict the strategy of the diplomatic echelons, and no less importantly, it was not our ethical approach.

Therefore, we had to come up with a new method. I remember it like it was yesterday: we told ourselves that the military doctrine we learned in training is not relevant. So we established an exceptional fundamental guideline not to move through the streets. It was also a matter of strategy to deny the enemy targets and to protect our soldiers."

The officers first floated the idea of moving entirely from rooftop to rooftop in the densely packed camp, but then came the eureka moment.

“Two weeks earlier, we conducted an arrest where we broke into the terrorist's house through the wall, and that's where the idea came from. We said, ‘Wait a minute, let's adopt this boutique solution and turn it into a method.’ That's where the technique was born, where we decide to create openings in the walls and pass through them from house to house,” he explains.

“During the discussion, numerous ideas were raised on how to make holes without causing the wall to collapse since civilians were living there, how to enter the rooms, and more. I remember the expressions on the faces of many in the room when I presented the new method to the division commander. Some expressed contempt, while others feared that it wouldn't work because we would be caught off guard in the rooms.”

While the breaching technique proved highly effective in minimizing Israeli casualties, it faced criticism back home.

“The wall-breaching method prevented extensive harm to Palestinian civilians. Unfortunately, one soldier, Chaim Bachar, may he rest in peace, was killed because he and his unit were forced to pass through an alley. It's an example of what would happen if many soldiers were walking on the streets,” he laments.

“Don't be mistaken, there was criticism the next day for the method and its brutality. Even in the eyes of the Israeli public at that time, it was not a consensus that it was permissible to apply pressure and engage in such actions to defeat terrorism. Today, it seems self-evident.”

The day after Kochavi and his troops swiftly seized control of the Balata refugee camp on the outskirts of Nablus, began what came to be known as “Black March". Almost no day went by without a terrorist attack and 131 Israelis were murdered. Kochavi and the young officers intensified the pressure for a full-scale occupation of the cities, with the successful takeover of Balata instilling them with a sense of security, but about half of high command opposed it.

10 View gallery

Golani Brigade soldiers marching through Nablus during Operation Protective Shield

(Photo: Courtesy)

"Together with several other brigade commanders and Division Commander [Yitzhak Gershon], we felt that the current operational method had run its course, despite understanding the broader considerations. We believed that the effectiveness of counterterrorism operations could only be achieved by gaining control over the city centers where terrorism thrived and developed freely and without disruption,” Kochavi explains.

“Three main concerns troubled those who opposed it: firstly, the potentially high number of casualties this action could entail; secondly, whether we were capable of effectively striking a significant number of terrorists and terrorist infrastructure, resulting in a substantial reduction in terrorism; and thirdly, the possibility of triggering waves of terror as in reprisal of our actions, exacerbating the situation.

All of these concerns were overshadowed by the historical assumption that it was impossible to defeat terrorism. This was another reason why the political leadership sought to find a diplomatic path by any means and refrain from unleashing the full military capabilities of the IDF to do whatever is possible.”

Whoever reads this might think you are implying that a large part of the year and a half of terrorist attacks could have been prevented had the IDF received the green light sooner.

"From the perspective of the political leadership, there were legitimate reasons to attempt and pursue the diplomatic process. In hindsight, we can say that it would have been right to make the decision to embark on Operation Defensive Shield months earlier, but there was a genuine, legitimate attempt to achieve a solution through non-military means,” Kochavi qualifies.

“The State of Israel has broader considerations, and the establishment of a unity government added to the divisions within it. The United States strongly pushed for a diplomatic process, and Israel wanted it to run its course while also maintaining its alliance with the U.S. The U.S. is a cornerstone of our national security considerations, and anyone who neglects or downplays this principle undermines a fundamental pillar of our security perception. Ours, not the Americans’."

Were there situations where you felt that the judiciary was tying your hands? We hear this accusation a lot these days.

"There were concrete issues surrounding types of arrests that could be carried out or the use of pressure on areas from which terrorist activity originated. For example, in the early months, it was forbidden to carry out vehicle seizures that assisted terrorist activity or make neighbors ask suspects to surrender, which has legal aspects," he says.

10 View gallery

Israeli troops deployed in Jenin during Operation Protective Shield, 2002

(Photo: Atta Awisat)

"The moment the Supreme Court, led by Aharon Barak, determined that the State of Israel is in an ongoing armed conflict with the Palestinians and that it is not a matter of policing activity, it was a watershed moment from which all references to counterterrorism methods changed completely, not only for us and the court but also for the international community, partly due to the high regard the Supreme Court holds in the eyes of the world. The greatest restrictions on our activities, up until Operation Protective Shield, were mainly derived from the limited objectives that were defined."

What can we learn from the Intifada in hindsight, over two decades later?

"The first lesson is 'yes we can.' The question that arose in my mind as chief of staff was how to achieve this 'yes we can' mindset. Because in the early months, it was clear that 'we cannot,' that defeating terrorism seemed impossible. Secondly, as the Paratroopers Brigade commander, I naturally wasn't exposed to all the discussions that took place within the military hierarchy and between us, the political leadership and the international community, led by the United States,” he says.

“Looking back, I learned and researched, even accessing protocols from that period. What happened was that within the political echelons and even within the military high command, there were different interpretations of reality and the warranted response, especially after the formation of the unity government. There was a duality regarding what was the right course of action. There was an attempt to stop terrorism through two conflicting means: limited military engagement and simultaneous diplomatic efforts or the use of other means, such as economic measures…

As a result of this ambivalence, it was very difficult to determine what type of operations were required. Too aggressive action would lead to a breakdown in negotiations, while minor operations would not be a deterrent and wouldn't effectively solve the problem, as the terrorists were in areas we were prohibited from entering. This lesson, which became increasingly apparent to me over the years, prompted me as chief of staff to try my best to create a shared and agreed-upon interpretation of reality at all levels, including a significant effort vis-à-vis the political leadership."

What's your takeaway from that today, in your personal life?

"To achieve victory, one must constantly and systematically adapt. It's not as if a sudden revelation descends upon you, but rather you must create mechanisms within your unit that constantly encourage critical thinking, learning and change,” he explains.

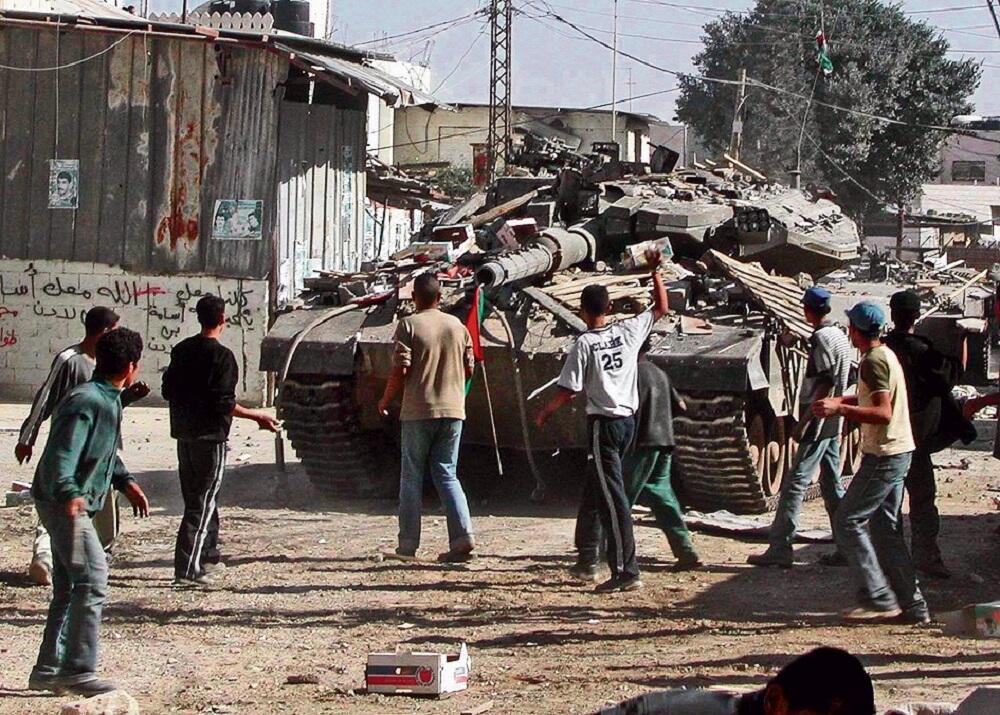

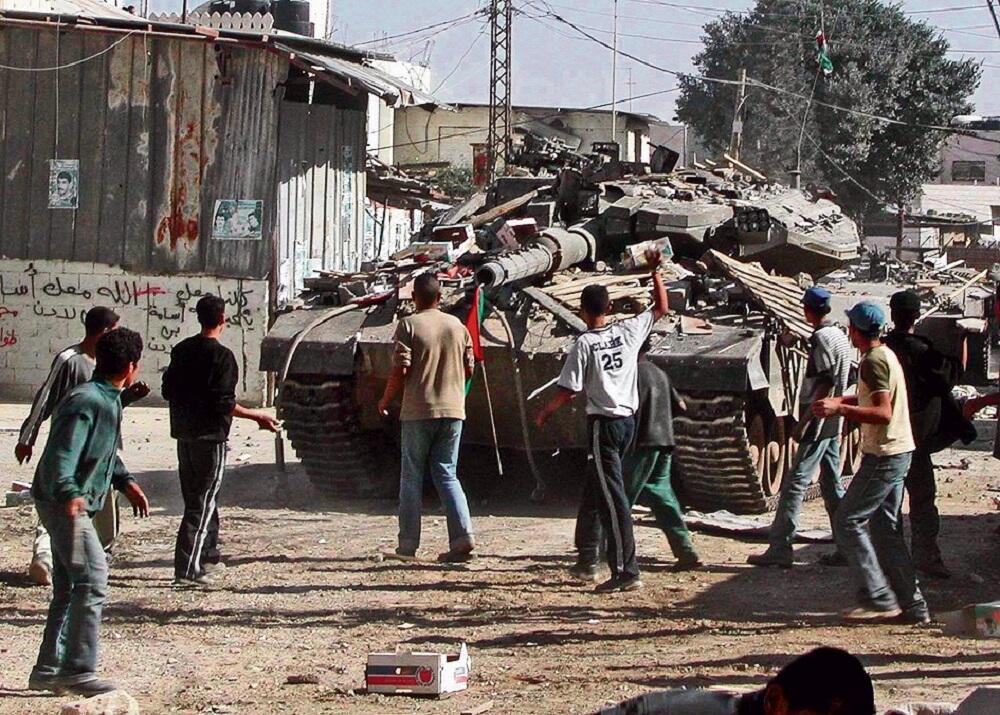

10 View gallery

Israeli tank rolls through Jenin during Operation Protective Shield

(Photo: Reuters)

Almost every day, we completed operations, extracted lessons, and discovered new combat methods. Every two to three weeks, we produced written theoretical material. The same applied to me as chief of staff. We made every effort and utilized all our resources in the IDF across all areas to continuously ask the question: What are the next opportunities? How can we find technology, develop new combat methods, and adapt? In any organization, existing doctrines and practices can act as a magnet, pulling it downwards and preventing change."

'It is possible to defeat terror'

The next round of fighting in Nablus concluded on the eve of Holocaust Remembrance Day. The soldiers were still scattered throughout the city, and Kochavi, whose family has lost many members in the Holocaust, decided to sound the siren in the Palestinian streets.

"My headquarters were tens of meters away from the casbah. We gathered loudspeakers from various places in the IDF and played the siren of Holocaust Remembrance Day to our soldiers dispersed throughout Nablus, and we held brief ceremonies wherever possible. With the battle not yet over and the weapons not yet cleaned, the ceremony held deep significance."

This act is highly symbolic, both toward the Palestinians, indicating that the city has been conquered.

"Ron, this was definitely not what I intended. It was not the sound of an alarm to state our presence. No, it was for ourselves and by ourselves. It was a moment that expressed three significant things: Firstly, we accomplished our mission, hitting more than 70 terrorists. It is possible to defeat terror, contrary to the entire history that taught us that even powerful armies could not eliminate terror worldwide, and here we are succeeding. This holds universal significance," Kochavi says.

"Secondly, we achieved it while upholding the values of the IDF and Jewish morality. It's a unique feeling. And finally, on the eve of Holocaust Remembrance Day 2002, with Israel defending itself by its own strength, without needing anyone's assistance. Just less than a month ago, I met someone who was there during the sounding of the siren, and he said to me, 'You don't know the sense of upliftment I felt at that moment.'"

10 View gallery

Israeli soldiers leaving Bethlehem at the end of Operation Protective Edge

(Photo: gettyimages)

Prof. Yehuda Elkana, an Auschwitz survivor, wrote in response to the First Intifada that the way we educate children about the memory of the Holocaust is the deepest threat to Israel's future, and that it instills the fear that everyone wants to annihilate us, feelings of persecution and victimhood.

"I'll start with the famous saying that just because you're paranoid doesn't mean they're not after you. In a more serious approach, I don't believe we should raise our children with a sense of being persecuted and that our enemies are trying to extinguish us every single day,” he reserves.

“We have many friends in the world, and we are surrounded by countries with whom we have peace agreements, shared security operations and diplomatic and economic engagements. Look at the coalitions we have today, each with its own characteristics - with Jordan, with Egypt, the Abraham Accords and many other countries. On the other hand, we cannot ignore the fact that we face threats on various fronts, threats that have even intensified, such as the Iranian nuclear threat.

With a balanced perspective, there is no room for extreme fear or on the contrary; we need to be vigilant, cautious and alert, to respond to threats, to try to expand alliances, treaties and peace agreements as much as possible. That's how we should educate our children, and that's how we need to look at reality."

10 View gallery

Rescuer examines the charred remains of a bus blown in a suicide bombing during the Second Intifada

(Photo: Elad Gershgorn)

In the Yom Kippur War, Israel died and was reborn differently, for better and for worse. Elites collapsed, trust in leadership and the IDF crumbled and from the void emerged, for example, the militant generation within the religious-nationalist camp, which fostered the settlement enterprise. In Lebanon in '82, we were torn apart for the first time, and the rift shook the IDF and hovered over it. How should we view the Second Intifada?

"From a certain point in the Second Intifada, a feeling developed among many Israelis that there was no one to talk to on the other side anymore, and the hope of reaching some sort of agreement with the Palestinians vanished for many. This is undoubtedly a turning point in Israeli society, but along with it comes a sense that we can defeat terrorism and remain moral. It is not self-evident; history has taught us how other armies fight against terrorism,” he says.

Future wars

In the past year, 31 Israelis and over 150 Palestinians were killed, reaching a peak not seen since the end of the disengagement from Gaza and northern West Bank in 2005. About a quarter of the Palestinians killed were minors. I ask Kochavi, what would a third intifada look like.

"I can't say if there will be one, but the operational methods of the IDF and the Shin Bet have become highly sophisticated," he responds. "Take what has been happening every night in the past year, what started with Operation Breakwater in March last year, and take recent operations in Gaza. You see the highest level of intelligence, which can pinpoint terrorists and apprehend them, and when apprehension is impossible, then to strike them, as in Gaza. Of course, the scope of hitting ammunition depots, communication rooms, command centers and rocket launch sites has also increased.

"I suggest not making any generalizations and seeing Arab Israelis as a group aligned with our enemies in this conflict. Arab Israelis are citizens of the State of Israel. Even in Guardian of the Walls, truth be told, it was a very small minority. The majority of them, by the way, were individuals with criminal backgrounds, motivated not necessarily by nationalistic reasons. Nevertheless, we must be prepared for scenarios where malicious actors attempt to hinder and undermine the national effort"

This is in contrast to Operation Protective Shield, whose main objectives were to regain control and freedom of action in Palestinian territories because today we have complete control over the West Bank, demonstrated every day through precise, professional and courageous operations by IDF units. Until the Park Hotel bombing, we tried to solve the problem from the outside in, with partial entry into Palestinian cities and villages. But at a certain stage, we realized that only full control of the territory and our presence in the area would allow us to effectively fight terrorism."

How justified is the concern that Arab Israelis will become involved in the conflict or potential for internal clashes like during Operation Guardian of the Walls?

"I suggest not making any generalizations and seeing Arab Israelis as a group aligned with our enemies in this conflict. Arab Israelis are citizens of the State of Israel," he says.

"Even in Guardian of the Walls, truth be told, it was a very small minority. The majority of them, by the way, were individuals with criminal backgrounds, motivated not necessarily by nationalistic reasons but rather by seizing an opportunity.

Nevertheless, we must be prepared for scenarios where malicious actors attempt to hinder and undermine the national effort. One should assume that war has an impact on all areas of Israel, not just what happens in Judea and Samaria, and as a result, it can have an influence on a specific segment of the Arab Israeli population."

10 View gallery

Kochavi in the field during his days as military chief

(Photo: IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

What will future wars look like?

"The IDF in 2023 not only differs from what it was in '82 or '73, but also from just a decade ago. Each brigade now has a sophisticated intelligence apparatus akin to the movie The Matrix, providing real-time intelligence," he says.

"Every brigade is equipped with a number of organic or external attack cells at the division and command level, enhancing its combat capabilities beyond its inherent capacity. The digital connectivity between branches and various units has greatly improved, and the quantity of explosives and missiles under the IDF's control has significantly increased. This is the warfare of the future."

You've been familiar with the subject for years, and you're also a philosopher and a technologist. How does the future look, and particularly how will the battlefield change?

"Among all the technological revolutions, artificial intelligence (AI) is likely to be the most radical, for better or worse. The IDF recognized this field years ago and harnessed it to enhance combat effectiveness," he says proudly.

"One example of this is the Targeting Directorate established three years ago. It is a unit comprising hundreds of officers and soldiers, powered by AI capabilities. It is a machine that processes vast amounts of data faster and more effectively than any human, translating them into actionable targets. In Operation Guardian of the Walls, once this machine was activated, it generated 100 new targets every day. To put it in perspective, in the past, we would produce 50 targets in Gaza in a year. Now, this machine created 100 targets in a single day, with 50% of them being attacked."

But Kochavi states that not everyone in high command shared his view on the benefits of the emerging technology. “Four years ago, we held a series of workshops to update the IDF's perception of warfare, including an analysis of the potential contribution of artificial intelligence. One of the senior generals approached me and said, ‘Enough already, artificial intelligence doesn't win wars.’ He meant unlike missiles and combat platforms. After Operation Guardian of the Walls, I asked him, 'So, what were you saying?'."

However, he is also aware of its potential drawbacks and risks. "Artificial intelligence poses extremely grave risks, and to a large extent, the genie is already out of the bottle with the release of numerous AI tools online. The world will need to address this issue, define it, establish strict regulation, determine fundamental control mechanisms, enforce punishment and invest heavily in education and explanation," Kochavi adds.

"Alongside the immense potential and tremendous contribution of artificial intelligence to humanity, it is capable of replacing and even alienating humans from decision-making altogether, including decisions about themselves. Artificial intelligence will possess far more knowledge than any individual, potentially relying on its own decisions more than on ours. The concern is not that robots will take control over us, but that artificial intelligence will supplant us, without us even realizing that it is controlling our minds. It will choose what we do, what we buy, what decisions we make, where we go and with whom we spend our time.

This may raise profound ethical and social questions, and when used by individuals, organizations and countries with low moral values, it can be extremely dangerous."

It seems we don't grasp the extent to which existence as a whole is about to change: the convergence of the death of privacy, the death of truth - including the emerging deepfake phenomenon - and genetic engineering with technology that already allows us to program reproduction. Nobel laureates will tell you that we are the last generation of Homo sapiens, and natural selection is coming to an end, all together with AI.

"Two concepts are going to be put to the test: the concept of truth and the concept of liberty, with an emphasis on personal freedom. They will be challenged more than ever before. This raises the most serious questions regarding the future of the individual, society and the state. When the Internet first emerged, few, if any, experts were successful in charting the highly positive and highly negative directions in which it would evolve. The same goes for the digital realm. If those were difficult to foresee, the challenges presented by artificial intelligence are several magnitudes greater," he says.

"It is possible that even humans will not be able to cope with the intelligence of AI and the need to tame it. However, AI will be designed in a way that it will be obliged to find checks and balances within itself. The main question and challenge will be whether the human species will be able to identify the mechanisms and safeguards against these risks in the future. If it were possible to develop ethics based on artificial intelligence, possessing power and capabilities like the directions in which AI is evolving, it might have been able to safeguard and protect us from itself. In any case, the checks and balances of artificial intelligence are undoubtedly a central goal for all countries in the world, and only global cooperation will enable us to successfully deal with it. Judging by the world's collective response to the climate issue, it is not encouraging."