Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

“Will you be traveling with the car outside of Germany?” asked the car rental clerk. “You tell me,” I replied. “I’m going to Sonneberg.” She smiled in an annoyed way and said that Sonneberg is still in Germany but advised me to take out the full insurance.

More stories:

Sonneberg is the name of a district where, a few weeks ago, a lawyer named Robert Sesselmann, 50, was elected as district administrator. He is the first representative of the far-right Alternative for Germany party (AfD) to win a local election.

Traversing picturesque scenery and enchanted evergreen forested hillsides, this is where I’m going. Every now and then, I come across a location that reminds us that bad things can happen in the most beautiful of places: Here a demonstration against Muslims; there was a neo-Nazi attack on a synagogue on Yom Kippur; nearby a refugee hostel that was set on fire. Only by going deep into the small villages inside the forests will you see the very heart of discrimination, xenophobia, racism and the enormous support for Nazism that this region has spawned.

Before delving into the nitty gritty of this election and its reasons, a number of issues should be clarified: A decade after its inception, AfD is making headway in the country’s second smallest district (56,992 residents). It’s a small, and insignificant victory in terms of the party’s influence.

Sesselmann is no more than an administrative director tasked with implementing decisions of the German federal government and of the district council. His jurisdiction is entirely local. He will receive instructions from above regarding the number of refugees to be absorbed for example. But he will be able to decide whether, through the winter months, these refugees are to be housed in closed halls or in tents.

Sesselmann’s election victory is symbolically important for two reasons: He’s part of the country’s growing support for his party (18%-20%), second only to Chancellor Olad Scholtz’s ruling Social Democratic Party (SPD), which has now won its first victory in any kind of election. Sesselmann won 52.8% of the votes, even in the face of all other parties uniting against him. Even if AfD doesn’t win any more local elections any time soon, city mayors and other districts will be forced to cooperate with it.

The roads leading to the home of Regina Müller on the southernmost tip of Thuringia, one of 16 states that make up Germany, are surrounded by Sesselmann’s posters and banners with provocative texts like “One of Us” and “Your pension money went to immigrants.” This is the AfD campaign: instead of addressing local issues such as parking, refuse collection or building children’s playgrounds, they’re honing in on national problems over which Sesselmann has no influence.

Müller, 43, works for a pharmacology company. She’s the nightmare of all liberal and democratic Germans. “I’d never voted for AfD,” she tells us. “But then I went to their lectures, conferences and information stalls in the town square and their evenings in beer gardens and I listened to what they had to say.” Increasing numbers of Germans go through this very process and are enticed by the option of an alternative – a party with the greatest presence, both physical and on social media.

“There’s a big problem with government in Berlin, mainly the Greens. These are people in Berlin who don’t own a home or a car, and they want to dictate to us how to drive our cars and how to heat our homes. We don’t want them in our homes. We want to heat our houses with gas and logs. They’re spending too much money on Ukraine and on immigrants, but our salaries are still 10% lower than in the West and our pensions are 18% lower.

We’re a long way from Berlin. We’re not foreigners. No one cares about us. I also don’t understand why they have to bring foreigners here. If a person comes from Syria to Turkey – why can’t they stay in Turkey? They want to come here because we’ve become the world’s welfare department.”

From what you’re saying, they persuaded you to vote for AfD

“No. I couldn’t. It’s a far-right party with a lot of Nazis in it. I couldn’t vote for them. But it's not a bad decision. I know lots of people who’ve realized that the conservatives have completely adopted the same platform. So, they ask themselves why should they vote for an imitation if you have the original?"

Her parents, Nicole and Hubert, join in. The father is fixing the balcony on Regina’s second floor. They mainly talk about the local residents’ greatest enemy – the Green Party, an important component of the government in Berlin.

When people here talk about the Green Party, it’s always followed by spitting. “Change is very hard for us,” says Hubert. “We felt a great sense of hope with the change we experienced with the union. We don’t feel that hope was fulfilled. Our degrees and professional qualifications weren’t recognized and we got lousy jobs. So, change has been very traumatic for us. The Green Party is never-ending change: A lot of drastic changes all at once: Refugees, COVID, Ukraine, inflation, battling climate change and heating laws, transgenders, talk of gender – it’s all too much for us. We just want to go back to the way it was.“

To East Germany, to the Stasi?

"No. We value freedom and democracy, despite not having the money to appreciate them. But we do miss the sense of security, planning our lives five years ahead, not having to think. Someone did that for us. These changes are too big for us and this election was the outcome. You also have to remember that whoever can, leaves this place. It’s the old, conservatives who are left here. Young people with no future inherited their parents’ embittered hatred of foreigners. It’s a deadly mixture.”

Despite the impression you might get listening to this family, the region’s economic circumstances are not the distressed kind on which far-right ideologies thrive. Household income in the region is above average and the local unemployment rate is 5% lower than the national average. Managers of the many local factories and the Chamber of Industry both talk about a dire shortage of working hands.

Many in Sonneberg say that they don’t care if the local economy collapses. They just want the place clean of foreigners. "They’re proud that they have put Germany to shame, that Germany has been presented to the world as such, while she’s trying so hard to distance herself from such a label.“

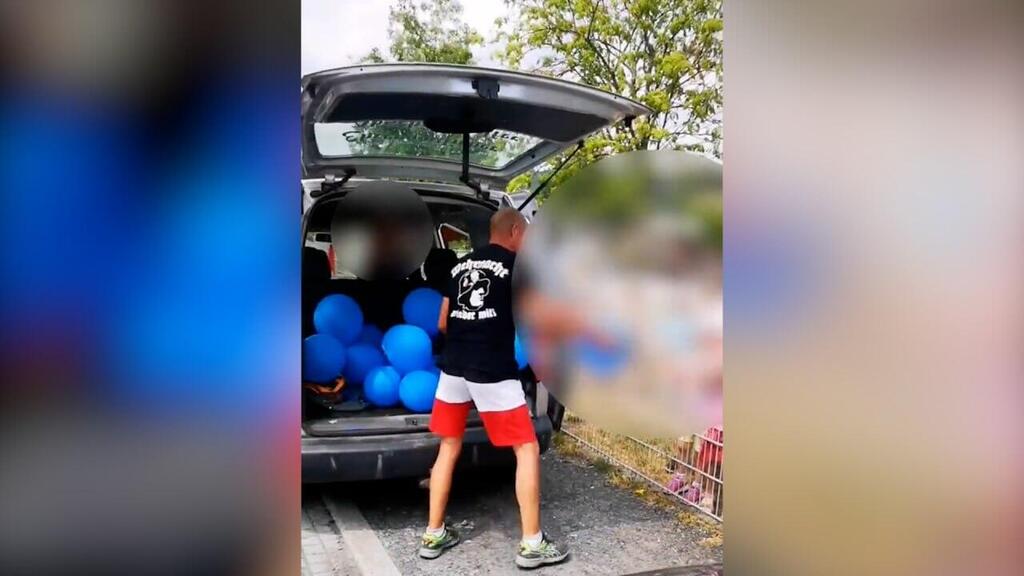

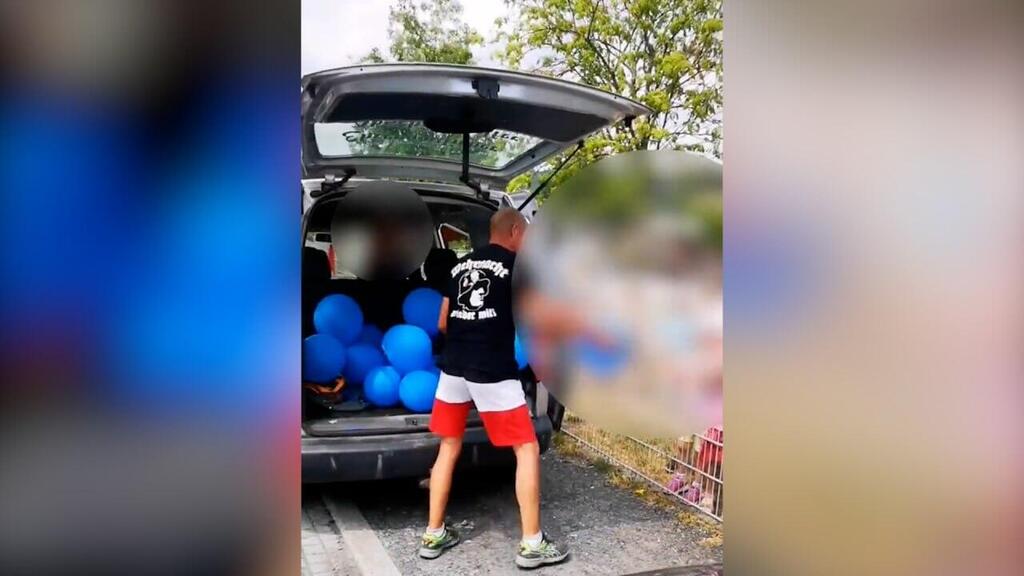

There’s a kindergarten not far from the Müller home. The day following the election, a local man named Daniel Winkler - father to a child at the kindergarten - drove up to the kindergarten in his car displaying a sign reading “Volunteering to expel people” and started handing the children balloons in AfD party colors. He had balloons in his car with the AfD slogan.

11 View gallery

Man in Nazi shirt hands out balloons in a children's park a day after the far-right's victory in Sonenberg

The kindergarten teachers stood there doing nothing. Winkler was wearing pants in the colors of the Reich - white, black and red - and a shirt with a picture of a soldier donning a Wehrmacht helmet inscribed with the words “Wehrmacht Wieder Mit” - a wordplay on the term “Wehrmacht”- meaning “Who’s joining us again?“

The following day the “Sonneberg Against Nazis” organization released the video of Winkler distributing balloons. It turns out that Winkler is a devoted Nazi from the more militant wing of the Neo-Nazis. He was active in extremist Neo-Nazi groups and has published a great deal of Neo-Nazi material online. He was under surveillance for making contact with a terrorist network that murdered nine people over immigration as well as a policewoman. None of this prevented him from attending AfD events and conferences and being photographed with party leaders Björn Höcke and Sesselmann, volunteering at Sesselmann’s headquarters and helping out as an observer during the elections.

As I was filming next to the kindergarten, a young couple deviated from their jogging route in my direction. I asked if they were willing to be interviewed. They said “We admire what Israel is doing to the Muslims”, but they don’t talk to the “lying media”, raised their right hands loudly declaring “Heil Hitler” and went back to their run.

The German secret service estimates that around one thousand of the 28,000 registered AfD members are far-right extremists. Björn Höcke is party leader in Thuringia. His immunity was removed when investigated for using Nazi slogans and denigrating the Holocaust. He remains extremely popular within the party. Sesselmann hugged him as soon as the election results were finalized.

AfD is already the most popular party in Thuringia with polls predicting 30% of the votes in state elections. All this, despite the Thuringia party branch being declared extremist by the German secret service, accounting for the surveillance using all possible means. (Other party branches are merely suspected of being extremist). The problem is that the harder German authorities try to restrict the party, the stronger it gets, accruing more voters, even in the West, normalizing its public perception.

AfD was born out of the Euro crisis. Four years later, in 2017, it became the first extremist right-wing party to be elected to the German parliament on the immigrant crisis card. In the 2021 elections, the party lost ground, down to just over 10% as it was eulogized by Germany’s intellectual media.

"The thing to remember about AfD is that it has a solid ten percent. No party has such a base," says Prof. Ina Redezeit of the Political Science Department at the University in Thuringia’s capital, Erfurt. “Then everything that’s happening in Germany just builds on that. The immigration problem, their ticket into the national conversation. The economy is stagnated. And there aren’t any very energetic solutions. Dependency on China, supporting Ukraine, the problems of transition to a digital economy.

All these have created one layer upon another of people who aren’t happy – looking for an alternative to the old parties. There’s a deep sense of disgust, neglect, fear and self-disappointment. Why can’t we give our children what our parents gave us? After taking hold of the poorer sectors of society, AfD is now making inroads into the middle classes.“

“The responses of the upper class have been absurd. They want to cancel Sesselmann’s election victory, or outlaw AfD – after they won!” This feeds directly into their feelings of neglect and discrimination. And if the party gets canceled, will these people’s ideas and sentiments also get also canceled? They’re 20% of the German electorate - too many people to cancel. We need to come to terms with the fact that they’re there, and ensure that more voters don’t join them. You need to go out into the field and listen to them. That’s what AfD do.”

“People here have changed their ideas from Communism to a sweeping support of the extreme right,” says local sociologist, Anka Bagrich. “They’re fed up being left behind, so they’ll do anything for the attention, even taking radical steps. We used to think that being against foreigners involved adopting a certain cultural narrative and identity, but now most AfD voters are completely normative people. It’s legitimate to vote for them and it’s legitimate to be seen next to people like Björn Höcke. Next year, three states - Thuringia, Saxony and Brandenburg - are holding elections. Elections that will challenge Berlin.“

Michael Debass is a cleaner for “Blaschka”, a company manufacturing orthopedic products that voted for AfD. He’s a perfect example of the mindset described by the experts. “I’m fed up with all of Germany’s foreign policy being based on her past,“ he says.

“I wasn’t to be able to love my country without having to apologize and without having to be an extremist. What they did with the immigrants was a betrayal of the German people. We have more crime. My girlfriend’s afraid to walk around town in revealing clothing because of what people will say to her. I would never treat their women like that.

For them, I’m a second-class citizen. The Greens got 0% here, and they want to decide what happens here? It’s a war. The Greens are on our borders and we’re fighting back. I don’t want gender-neutral language and I don’t want refugees, although I’ve got nothing against refugees. “

What do you mean you 'have nothing against refugees?' You voted for a party with that as its manifesto

“It’s not against refugees. It’s for Germany. All the other parties have adopted the same platform, and then say that AfD is extremist. If they cancel us, we’ll know for sure that we’re not living in a democratic country. The same people who, eight years ago, came to shout at us about how we were Nazis for supporting them, are now active in the party. The “environmentalists” in Berlin think I’m a stupid country bumpkin, but at the ballot, my vote is worth the same as that of a leftist environmentalist. These elections have been the lightning – the thunder will come next year.“

After the First World War, Thuringia was among the places where the Nazi party joined local government. Erfurt was Hitler’s overnight of choice en route from Bavaria to Berlin. The nearby Bavarian city of Coburg elected the country’s first Nazi mayor. In 1932, the city granted Hitler honorary citizenship of the city.

Neighboring Coburg is a rich and vibrant city. The day I was there, there was a gay party in the city center – full of foreigners. Fifteen miles away and worlds apart. “Before COVID, we tried to connect with AfD supporters, to understand how they think,” says Amadeus Schrampf who works in a plant manufacturing packaging materials.

“But during the pandemic, they’d come into work unvaccinated and didn’t want to wear masks and it shocked us. It’s as if apart from being German, we had nothing in common. If you don’t want to wear a mask, stay at home. I’m giving you a job and you want to kill me? Are they crazy?”

We went to a Burger King at a parking lot adjacent to a gas station. “Look,” he says. “Thirty youngsters from Sonneberg hanging around the parking lots smoking hookahs, saluting each other and shouting Heil Hitler.” It goes on all night.

I asked why here. “I can’t explain their logic,” he says. “Except for them having no logic. Nothing.“

The day following the Sonneberg victory, the conservative party leaders pronounced the Greens as the main enemy and that they must be fought. Adopting far-right policies has become a popular tactic across Europe – to steal votes from them. AfD’s tactics are clear: to garner strength in villages and municipalities, to show that everything works just fine when they’re in charge, and then force other parties to cooperate with them, even at a national level.

“It used to be that if someone was far-right or a fascist, no one would vote for them. They’d be taboo,“ says Müller. “Now they vote for them for those very reasons.”

At a rally in October, Sesselmann, who is from Sonneberg, described Germany as no more than a “puppet government of the USA” and that the war in Ukraine was started by the United States and its victims are Germany and the EU countries. The claim of lack of German independence is a mantra in this political camp. These speeches and the extremist actions carried out by the right have received no real response from legal or judicial authorities. For 30 years, the far-right feels it’s okay to attack foreigners.

The people of Thuringia and Sonneberg are proud of their extremist stances. Although far-right politicians are offering racism that poisons democracy, they’re strong and united, not constantly arguing like other parties. The new district administrator in Sonneberg has been elected for a six-year term. Enough time to legitimize hatred and racism.

“We’ve been ignoring the problem, thinking it would just go away,” says local resident, Heidi Bünter. “And all of a sudden, they’re a people’s party. Good God. Could you imagine a single tourist coming here knowing they hate foreigners here? Maybe they’ll come to see Nazis – like in a zoo. They’re very clever people. That’s the frightening part. They always manage to turn an economic threat into a culture war. It happened against the immigrants and it’s now happening against the government and its ecological policies.

They make people afraid – not of their bank accounts - but rather about their cultural identity. It’s an ugly, devious campaign, but very clever. You have to be in contact with them, but it doesn’t happen. They feel that the Greens are trying to reprogram them, that they’ll work against themselves. You talk to them about giving up their diesel cars. That’s sacrosanct.“

Sonneberg is home to just over 58,000 residents. Over 20% have left in recent years. A decade ago, foreigners made up less than 2% of the population. They currently number 8% (the national average is 13%).

Zola, the butcher at “Orient Market” on Gustav-König-Strasse is happy to have arrived in Germany from Syria five years ago. “There’s work. Everyone helps. You don’t wake up every morning wondering if you’ll still be alive by nighttime.“

And the rise of the right doesn’t scare you?

“Habibi, we lived through Assad’s dictatorship and everything we went through and everything we lost along the way – we’ve used up a whole lifetime’s supply of fear.“

In Erfurt, they’re still staging demonstrations against building a 30 ft high minaret on a mosque – in a city where the church spire reaches 75 ft into the sky. The demonstrations include dozens of residents of Erfurt and the surrounding area who show up in the small hours, and make a horrific noise – supposedly to warn the surrounding residents about the muezzin’s call to prayer upon completion of the mosque.

“They sometimes come into our neighborhoods," says Ramadan, a refugee from Afghanistan. “They tell us we’re not wanted. Last time this was socially acceptable, it ended in gas chambers.” He's wearing a T-shirt reading “Love for All. Hatred for None.”

A survey conducted by the University of Leipzig found that 50% of the residents of Eastern Germany are not happy with democracy as it stands today. Thirty percent agree that Germany needs one strong party. Not everyone who votes for AfD is a right-wing extremist, but everyone who votes for them is consciously voting for a racist, antisemitic, anti-democratic party.

Thirty percent believe that Germans are better than other people and that "Jews use dirty tricks to achieve their goals." Twenty percent believe that had it not been for the extermination of the Jews, Hitler would have been considered an excellent leader. Twelve percent hold extremist right-wing views, compared to just 2% in the West.

“AfD provides a legal home for people from the Neo-Nazi scene,” says local resident, Martina Kellner. “There are lots of businesses here who contribute to AfD and support them. AfD gives decent employment to psychopathic people as a cover. Living here is living in fear. We all know what’s happening right under our own noses and no one can save us or help us.“

On the other hand, Matthäus Wagner from the village of Haselbach boasts a decisive AfD majority: “Look. I heat my house with logs that I get myself from the forest. I don’t rely on the state, the suppliers or economic changes. I don’t want the state interfering with that. My home is my identity. This is where I escaped to from the Stasi, the union and the changes that capitalism has brought. I’m just asking that they don’t get into the last symbol of my identity, my place of refuge. And definitely not without consulting me.”

“The media has weakened,” says Markus Nilienthal. “They have their own newspaper that they give out for free. They’re active on social media and they control the narrative here. They like it when the secret service classifies them as dangerous as it’s a marketing tool and every action against them victimizes them. This time they won, even when all the other parties united against them. It’s a process of normalization.“

Katharina König-Preuss, a member of the Thuringia parliament representing the left-wing “Die Linke” party was born in 1978 in East Germany where her father served as a church minister. “My father was in the opposition. When I was a little girl, they’d put me in a corner and spit on me. My father once took some children to visit Auschwitz and they asked how people became Nazis. My father said that if he knew, he’d know how to cure them or fight them. It still rings true.“

When she was 18, as part of a project organized by her father, she visited Israel and fell in love with the country. She later returned to volunteer with the elderly for 18 months in Jerusalem. She has been returning to visit two or three times a year ever since. Upon her election to parliament in 2009, she was charged with the task of battling racism, fascism and antisemitism.

11 View gallery

Katharina König-Preuss holds up a sign against AfD leader Björn Höcke

(Photo: Ze'ev Avrahami)

Her office in Seefeld is jam-packed with anti-Nazi leaflets and posters. She also founded the “Haskala” project to root out antisemitism from within her own party.

Why don’t you demonstrate a presence like AfD?

“I can’t duplicate myself. We tried doing it once a month, but it was impossible. I don’t understand where their funding and manpower is coming from. On the other hand, they don’t do anything in the parliament. I have to read hundreds of pages every week to be prepared for parliamentary debates. They show up, sign in so as not to pay a fine, and then leave. When they are there, they talk to YouTube or Facebook. They have no desire to debate, just to market themselves. They just see what the Greens are doing and suggest the opposite. Zero activity on all fronts.“

Do you see yourself leaving?

“My parents’ friends say I should leave before it’s too late. There are already songs about how they’re going to kill me. I can’t leave, because who’ll stay to fight them? Who’ll protect those who can’t leave?”

Is there a red line?

“When they sing songs or say they want to put me in a gas chamber or call me a whore for the Jews, that’s one thing, but if they get to my family – that’ll be reason to leave. But what then? Where to? I don’t want them to win. I’m afraid. Very afraid.“

“Just before I left Sonneberg, I went to the AfD headquarters at Austrasse 5. The whole place is decorated with party flags and maps. It was locked shut. I sat on the steps in front of the building. An hour later, a school bell chimed and two schoolchildren came down the street. A German girl with an African boy. They were about ten, carrying heavy book bags. They were laughing and chatting. They exchanged glances, gestured with hands and parted ways, walking on opposite sides of the sidewalk for a few hundred feet. Like a hope box, filled with despair.”

“I got into my car, lit a cigarette, pushed down on the gas as hard as I could – to flee this cursed place, flee the hatred, the racism and the promises that this is just the beginning. The radio was playing a Simon & Garfunkel song. Raindrops started covering the windscreen. Another gentle song by an American singer came on the radio. Then the newsreader announced that in their municipal elections, the town of Raguhn-Jeßnitz had elected Hannes Loth as Germany’s first mayor elected on an AfD ticket."