Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

This coming January, Aviva Sela, member of Kibbutz Be’eri, will mark her 97 birthday. She says that as things stand, she won’t celebrate the occasion, only mark it. Perhaps, if by then (her birthday) she sees the return of her beloved grandson, Itay, currently being held in Hamas’s tunnels in Gaza, the son of her daughter Orit and Rafi, who were killed on that terrible day - she might, with great caution, call it a celebration. A small one, but a celebration, nonetheless. Meanwhile, Sela, the last of the founders that survived the massacre in the Kibbutz, wants “someone to explain to me what happened. How can it be that all this happened to us?”

Read more:

Shortly before that dreadful Saturday, Aviva had contracted Corona and still had a heavy lingering cough. Because of this, on the night before the massacre, she slept on a couch in the living room, outside of the safe room, and remained there when the alarms began to blare. It wasn't the first time Aviva had refused to go into the safe room. For years, Aviva and her husband Abraham, who everyone called Bamik, had acted in this way.

"We're too old to run to the safe room every time an alarm sounds," they told their children. And what will you do if there's an intrusion, the kids asked, and terrorists enter the kibbutz? "If they show up," she would answer, "I'll offer them coffee."

And that is, more or less, what she remembers happening. The terrorists stormed the house and took Aviva and Gracie, Aviva’s Filipino caregiver, out to the porch. This is our house, they shouted. You are living in our house. “Tfadalu” (welcome), Aviva told them. “Go on in.”

But before that happened, Gracie, the beloved caregiver, who would be murdered not long after, insisted that Aviva enter the safe room. She laid her in the big bed, laid down beside her, and in the photograph she sent to Osnat, Bamik and Aviva's youngest daughter, the two are seen head-to-head in the small room covered in a floral blue blanket.

Gracie sent the photo at 09:51, a little over two hours after the first message she sent at 07:34. "I'm in the safe room," she wrote, "Mom's still sleeping." Wake her up, Osnat wrote her once the extent of the terrible disaster that was happening in the Kibbutz had already leaked to the media. "Get her into the safe room at once and close the door." At 08:20, Gracie wrote that they were inside, together. And at 09:51, when she had sent the picture, she added that there was no electricity. "Stay there," Osnat replied, "We pray that it will end quickly." At 10:21, Gracie wrote again. "Mom's already gone out to the bathroom three times, and now she's sleeping again." In the photo she sent, Osnat told us, "You can see that mother didn’t have her hearing aid." The mercy of silence in the midst of the dreadful noise, the screams, the sounds of gunfire, and the sirens.

At 10:24, Gracie wrote that she was praying for it to be over already, and at 10:25, she wrote that she was turning her phone off because she wanted to preserve its battery. Then, at 10:28, she sent an update that she was hearing shots outside. At 11:44, this time using Aviva’s cell phone, she wrote to the whole family, “Help, someone has entered the house. We're inside the safe room. There are people inside the house. I'm scared. Help us. Help us. They're looking for something in the house. There's a lot of people here. Please help." That was the last message.

"Everything seemed odd, very odd to me", Aviva says today, sitting on the sofa on the porch of her son Danny's beautiful home in Kochav Yair. Surrounded by family, she recounts what happened, peeks out above her glasses, adjusts her hearing aid, and closes up from time to time, escaping into the comforting fog of repression and forgetfulness. "This was the first time Arabs came in this way to the kibbutz," she says out of nowhere, "I grew up with Arabs and I never saw anything like that, and until this very moment, I’m not sure if it was real or a story that somebody told me." And it wasn’t entirely clear what she saw or heard, aged 96, without her hearing aid, for some of the time even without her eyeglasses. That is, until she decided to get up from the swing upon which others had placed her and began walking.

“I left alone, already without Gracie, I decided that I need to get out of there. I didn’t hear a thing. I also didn’t see anyone. It was egotistical of me, to leave everything like that, and until this very day I don’t understand how I did it. Maybe it was fear that drove me.”

“I left alone”, she tries to recall, “already without Gracie, to the kibbutz’s parking lot. I decided that I need to get out of there. I walked slowly, with my walker, slowly, slowly.” Gracie had managed to put her medications in the walker’s basket, as well as some fruit and a change of shirt. “It was quiet all around” she says, “I didn’t hear a thing. I also didn’t see anyone. It was egotistical of me, to leave everything like that and look for a car that would take me away from there, and until this very day I don’t understand how I did it. Maybe it was fear that drove me. There was one man with a car in the parking lot. I asked him where he was going to. To Tel Aviv he told me. So, I’ll go with you, I told him. And we drove away from there.”

That was around 16:30. Heavy fighting was still going on in Be’eri, and through the gunfire Aviva walked, with her walker, as if she were walking through a land corridor in the middle of a stormy sea. Her neighbors that were there were able to tell that an elite unit that arrived at the location gathered up some of the survivors, including Aviva, and somehow, in a way that isn’t entirely clear, she was taken to a nearby area known as “Shula Hill”. One of the friends contacted the family and Osnat left to get her. She picked up her elderly mother somewhere along the way. “So what do you think?” Aviva asks me, “Did it really happen or was it a story?” Then she is quiet for a moment, and lifts her head again, “How is it that we didn’t know ahead of time,” she asks, “Why wasn’t there any intelligence?”

“Itamar’s Team”, Less One

She was born in “Nesher” (near Haifa) to parents that had come from Poland. She grew up, as she puts it, "In the shadow of the Balad al-Sheik Arab settlement," and she lived this way, she tells us, in Be’eri, as well. "Always in the shadow of the Arabs."

Go home, they told Aviva’s mother at the hospital in Haifa when she went into labor, there's time. That was January 1927. However, by the time her mother had walked down to the Lower City by foot, her contractions had gotten worse, and Aviva, in an interview she gave to Be’eri Archives some nine years ago, said recounted that she had nearly been born on the stairs. Her parents, Shmuel and Rachel Rosenthal, immigrated to Israel together with a group form the Gordonia youth movement, and Aviva grew up in a “Zionist home”. Her father, who worked in the "Nesher" cement factory, was a “Mapainic” (labor party), like all of their neighbors", but on Friday evenings her mother lit candles (in honor of the incoming Sabbath) in candlesticks that Aviva had saved for nearly 80 years, until the terrorists came to the door and screamed that everything in the house was theirs.

She recounted how, during the 1938 riots, the Arabs of Balad al-Sheik, Tel Hanan at present, would shoot at passing cars and at the neighborhood’s homes, and that in one of the murderous attacks a father protected his infant son. "The father was killed, the baby survived, and for some time, the widow stayed with us with the baby in our shack." Did she think that 85 years later, the same thing would happen in the house she built at Kibbutz Be’eri? "No, I never thought it would."

When she finished 12th grade, she joined a “Garin” (a group that serves together in the army, both to help settle the land and as infantry soldiers) of the “Noar Oved” youth group. She underwent training at Gadera, where the kibbutz’s first children were born. “And I was sent to a kindergarten teacher’s course. Not that I wanted to do the course, but that’s what had been decided.” At that time, she met Bamik, a native of the Borochov neighborhood in Givatayim. They were married in 1949 in her parent’s backyard.

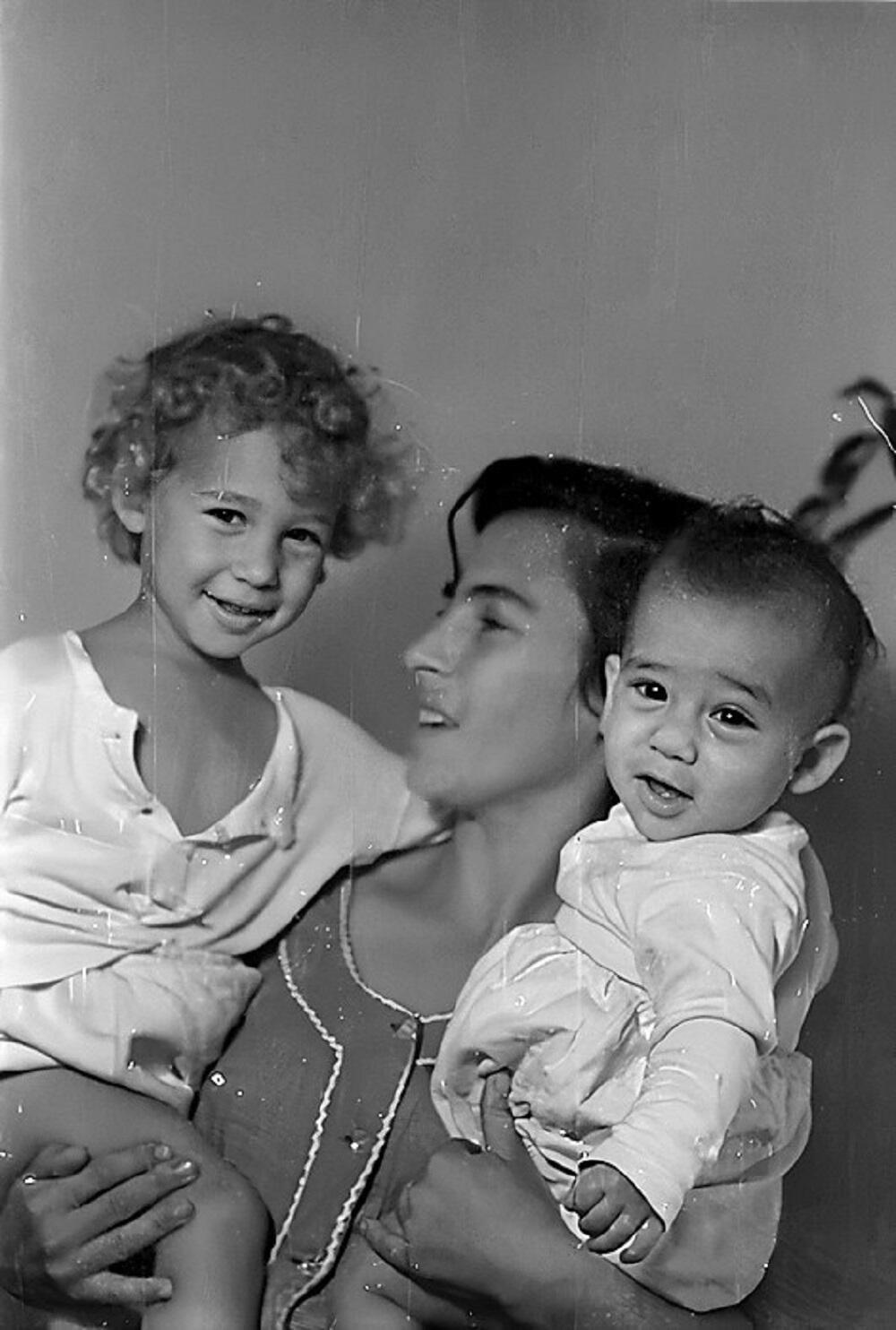

3 View gallery

Aviva Sela as young adult with Danny and Dorit, two of her children

(Photo: Family Album)

“I loved everything about the Kibbutz, even the communal sleeping arrangements.”

At the closing of Yom Kippur, 5707 (1946), the first settlers arrived at the land of Nakhbir (Old Be’eri) and fought there during the War of Independence. Bamik, who was Yigal Allon’s right hand man in the 60s, and later on the kibbutz’s internal secretary and economic coordinator, became in time one of the print shop’s mythological managers and one of those who developed some of the kibbutz’s leading brands. Aviva served in many positions, including being the school’s principal, and she is best remembered from her time as the kibbutz's technical secretary and her ability to give each of the members personal attention. Both of them were among those that the kibbutz defines as the "physical and spiritual founders of the place."

Itamar, the eldest son, was born in 1950. 53 years later, the book "Itamar’s Team", written by Avner Shor, was published. It told the story of the company of soldiers in “Sayeret Matkal” (the IDF’s most elite special forces unit) that Itamar had commanded, the team on which Avi Dichter was a soldier. The same Dichter, who is now a cabinet minister, that three weeks ago was asked, in unambiguous language that cannot not be interpreted otherwise, not to attend the funeral or the shiva of Orit Swirski, Itamar's younger sister. The entire team was there, at the cemetery surrounded by giant eucalyptus trees, standing in the heat at the end of the horrific October, with hundreds, perhaps thousands, who came to accompany her on her final journey. Everyone except Dichter.

Itamar, her eldest son, was Avi Dichter’s commander in “Sayeret Matkal”. The entire team accompanied Itamar’s younger sister, Orit, on her final journey. Everyone except Dichter, who was asked not to attend her funeral or the shiva.

Orit, who just a few months earlier had celebrated her 70th birthday, was murdered at her home in Be'eri. The house that bloomed, that had been filled with art treasures that Orit had gathered one by one with great love, was burned to the ground. "There were four of us," her brothers said at the funeral, "Itamar, Orit, Danny and Osnat. We've remained three. After her departure from this life, we'll never be who we once were or what we dreamed to be."

"The beautiful girl from the 'Shibulim' class” they said in their eulogies, "a noble girl with green, good eyes, full of compassion, smart, a shining light." She believed in goodness, in what was right and worthy of being done.

She met Rafi Swirski at the end of high school, tall, handsome, and smart. They married and had the twins, Merav and Jonathan, then Yuval and Itay. "With unending devotion," the family says, "she was at her parents’ side, as they passed the age of 90. Both before Bamik passed away, three years ago, and afterwards." In the midst of our own Holocaust of 7.10, Aviva insisted on knowing the fate of her daughter. "I have a daughter there," she told whoever would listen, "I have grandchildren."

One of the grandchildren, Itay, 38 years old, was taken hostage. His brothers are incessantly looking, fighting, begging, trying to save him, chasing down every bit of information. Day by day they fight an exhausting, crushing, heartbreaking war to bring him home. She doesn’t often ask about him, about Itay, Grandma Aviva's favorite grandson. Perhaps because she's showing mercy on the family, careful not to make any harder that which is already beyond bearing.

“Protect our Home”

On 15 March 2017, in a letter that Aviva was asked to write to the members of the kibbutz, she wrote as follows: "We send our blessing to every home in Be'eri. Protect the place, guard our home, the kibbutz – there is nothing without it.” She knows today that the kibbutz without which there is nothing, has been destroyed. That the home where she raised her children, the place where her grandchildren came to be pampered, is no longer. She knows that the porch where she used to sit, with the hanging swing covered in colorful cloth, with the blossoming plants, that nothing remains.

But time deceives her, details are becoming lost. Do you remember the woman with the child? Osnat asks her while we are sitting on the porch and evening falls upon the quiet settlement, far away from the war’s inferno. “I don’t know” Aviva says. Testimonials are beginning to amass and take foot. The family collects the data, trying to piece together the pieces of the puzzle, in an attempt to understand what happened there during those hours, how it happened that their mother was saved.

One of the eyewitness accounts came from a kibbutz member that the terrorists chased to Aviva’s porch. She tells that a young woman arrived right after her, bleeding, with a three year old child and an eight year old child who didn’t stop asking what would happen to them. They murdered my husband, the injured woman said in tears. They shot him and my baby (girl). They shot her in the head. Now, she told her son, they will kill us too. Silence, the terrorists screamed, but Aviva, according to the accounts, continued to speak with the woman. She continued, so the woman wouldn’t sink into despair, wouldn’t fall asleep, wouldn’t die. The terrorists were shouting to be quiet, and Aviva continued to speak with the bereaved mother. And when the child began to vomit, she told him that it was alright, alright, that it was not a problem.

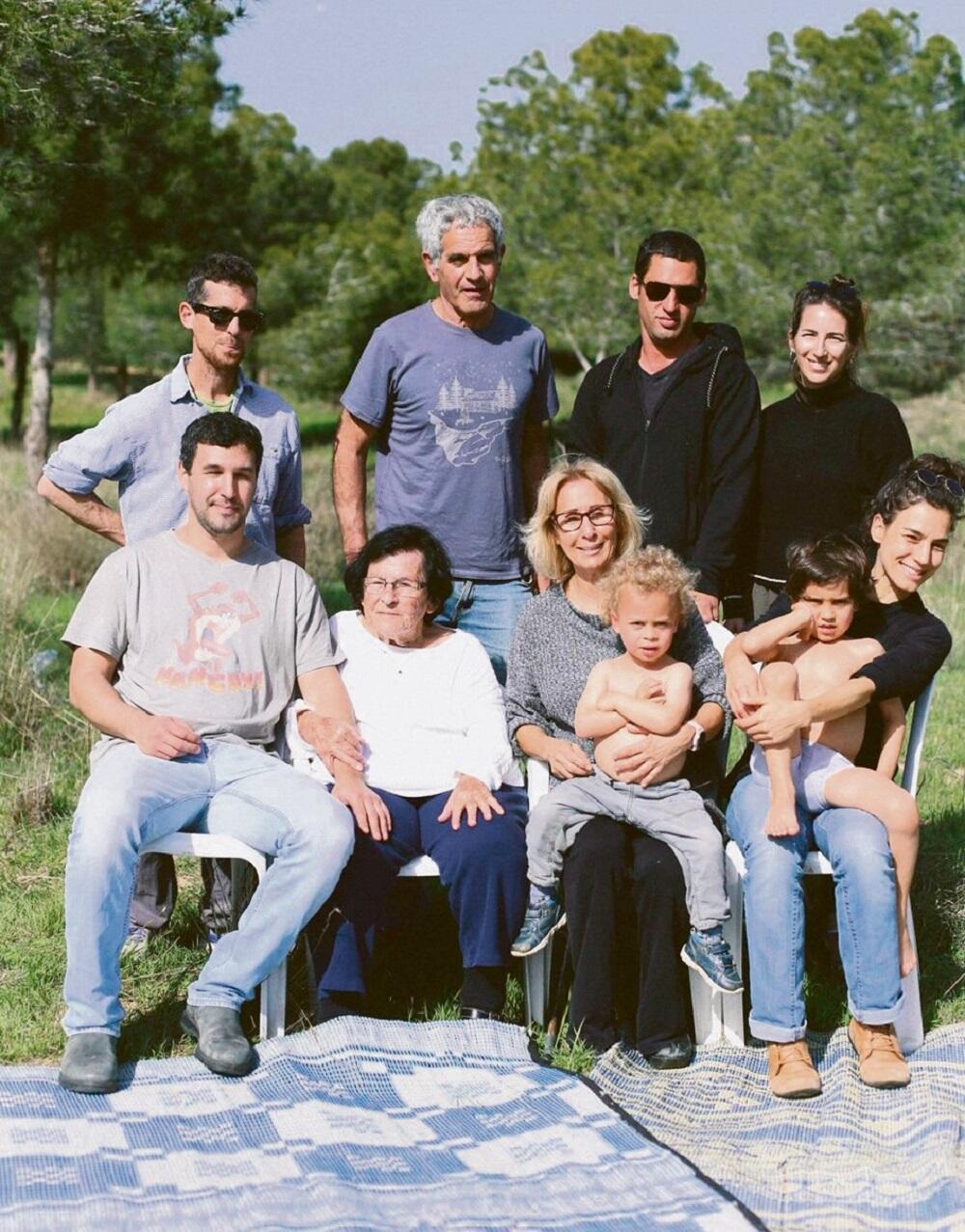

3 View gallery

Aviva Sela with Orit Swirsky to her right, who was murdered, Rafi Swirsky above her who was also murdered and the grandson Itai who is abducted

(Photo: Family Album)

Aviva still asks about Gracie from time to time. Even though she now has a new caregiver, Marisel, who brought a sweet little dog with her. A dog that, in the middle of great chaos, adopted the good-hearted caregiver. "People think they remember exactly what happened", says Osnat, "one of the women, who sat for 30 hours and held the door to the safety room so that the terrorists could not to break in, told the tale of what happened to her, moment by moment. She was sure that she remembered every detail. But a week later, when testimonials were cross-referenced, it became clear that things played out a little differently. For example, she did not remember that during her rescue, the soldiers that came to save her, led her, under fire, to the pickup point, and that in several cases she had to actually crawl."

And Aviva, who for years was responsible for writing Be’eri’s chronicles, a sort of daily recordkeeping that the kibbutz made sure to keep, didn’t write a word or document the terrible tragedy. She watches the news once a day, “at home, with Bamik, we’d watch the news all the time.” She doesn’t read newspapers either. When Itamar took her to visit her friends that were saved and transferred to Ein Gedi, she was happy to go. Happy to meet them. “Everyone’s there,” she says, “all of my friends.”

She knows that to Be’eri she won’t be going back. 85 people were killed in her kibbutz, and approximately 30 are thought to be held hostage by Hamas. All that’s left of the kibbutz she loves so much is dirt and ashes. “In the first decades (of the kibbutz’s existence) the conditions were rough, but we were young, and it didn’t bother us. We worked hard for a great many hours, and we lived life in it its simplest form. I loved everything,” she said in that old interview, “even the communal sleeping arrangements. I didn’t suffer from this, the opposite – shared education gave me a sense of security. I never felt as if I was dumping or abandoning my children. The children’s house was a part of my own home. If ever I felt disquiet for any reason and I felt that I needed to sleep alongside one of the children, I just did exactly that. I didn’t make ‘tsimis’ (a stew) out of it.”

And at the end of the interview, she said: “Not long ago we celebrated my 88th birthday with the children and their spouses, with the grandchildren and the great-grandchildren. We appreciate what is that we created, remember to thank the kibbutz for providing a strong backbone and offering social security – and we know that this is not something to be taken for granted. Now we are growing old together, each one of us with their own problems, but we aren’t alone. Relative to others of our age, our troubles are tolerable.”

When we finished our conversation, evening had already come. A soft darkness, not threatening, lit by the streetlamps. “So, what do you say,” she suddenly asks, “what’s going to happen?” Things will be alright, I say, because what else is there to say. Everyone already knows who’s no longer with us, everyone is waiting for those who are with us, but not here – Orit’s Itay, Orit who is not here. Because that’s what’s important right now. That Itay will come back. That’s what’s important and that’s what they’re working on now, everything possible so that he’ll be returned.