The Spanish Inquisition was founded near the end of the 15th century in Spain in order to enforce Catholic orthodoxy across Spain-controlled territories.

To achieve that goal, thousands of Jews were persecuted across the kingdom and given two options: renounce the Jewish faith and become Christian or be deported from Spain. Many Jews chose to convert, becoming Conversos.

Documents recently uncovered by the National Library of Israel showcased the ways in which the Inquisition persecuted descendants of Spanish Jews even after they had been forcefully converted to Christianity.

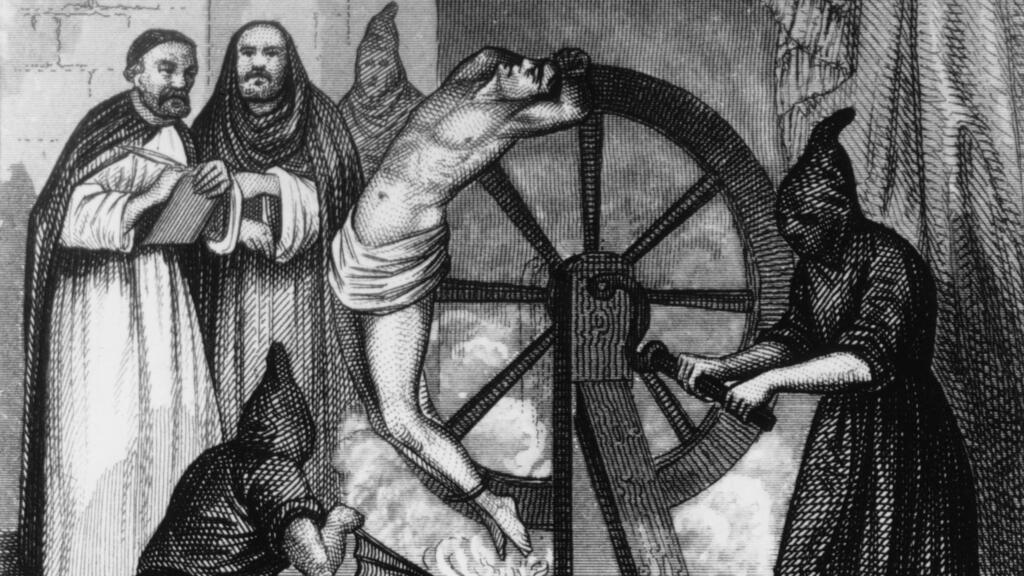

Dr. Aliza Moreno, a historian focusing on Judaism and the Inquisition, says that revealing lists made by Spanish clergymen make it clear they wanted to torture, question, and execute Jews who fled Spain and Portugal and continued to follow Jewish rites.

Jews in Portugal were forced to convert – unlike those in Spain who were also given the option to leave the kingdom – therefore the Inquisition believed that many Jews who converted only did so in order to avoid danger, and were continuing to follow Judaism in secret.

"The presence of the Inquisition in South America has been known in the research community for years," Moreno says. "However, despite the fact that I have long been researching this field, every time, I discover new things, thanks to their meticulous record-keeping."

"The Inquisition was a bureaucratic entity," Moreno notes. "The Conversos (Jews who were forced to convert) who were tried by the Inquisition in South America in the 17th century were more than a century removed from the time of their ancestors' expulsion or forced conversion. These people were born into Christianity and never or had any contact with Judaism.”

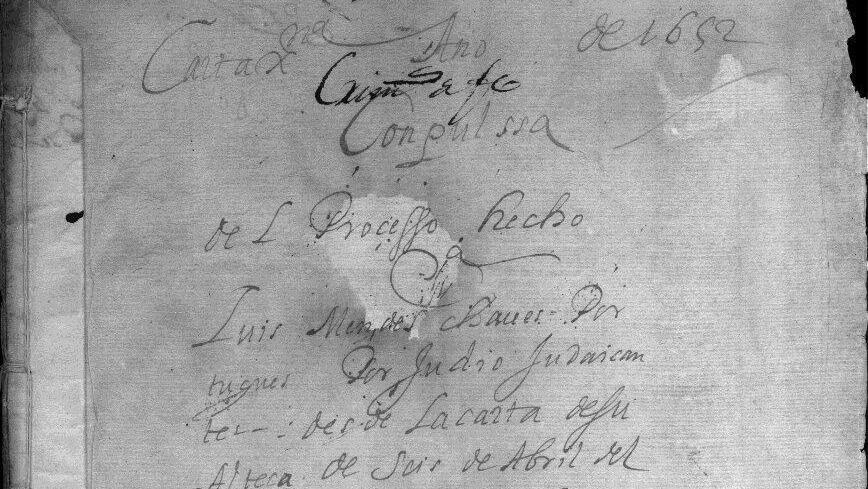

5 View gallery

Memorandum of interrogation made by the Inquisition

(Photo: National Library of Israel Archives)

How were they treated by the church?

"Converso families were stigmatized as disloyal to the Christian faith. They suffered discrimination, and there were restrictions that prevented them from being appointed to positions in governments or churche. The Inquisition would also hold interrogations and trials if they were suspicious of members of these families.”

How did the Inquisition attempt to uncover Jewish victims?

"The Inquisitors tried to make the interrogated confess to crimes attributed to them – for example, that they fasted on Yom Kippur, and that they believed the redemption will come from the 'Law of Moses'.

Inquisitors also made those they interrogated recount their lives, which were written down. You had to say where you were born, how many siblings you had, and what you did for a living. the suspects had no reason to lie about these facts, and it presents us with a mass of research-worthy material to work with.”

Dr. Moreno was born in Columbia and made Aliyah ten years ago. She now works in the National Library of Israel and is in charge of the library’s Jewish texts section. Moreno began looking into the Inquisition during her master’s degree in history and decided to pursue it using her native language, Spanish.

During her work toward her Ph.D., Moreno looked into interrogations made by the Inquisition documented in Columbia’s Cartagena de Indias. Converted Jews who immigrated to the Americas were also met by inquisitors who were sent to make sure no Jewish customs were being practiced.

The Inquisition, however, faced difficulties in locating where decedents of converted Jews who arrive in the Americas from Portugal, lived.

“Several generations have passed and the Inquisition had no way of knowing whether Jewish rites were still continuing,” Moreno says. “There were some abnormal cases where it was clear that some former Jews were still carrying out prayer in secret.”

“Luis Chaves, for example, who arrived on the shores of now Venezuela in the first half of the 17th century with a large load of Jewish books – was one such man. He carried prayer books, a Spanish translation of the Bible, a book of halacha, a piece of cloth that was probably a scroll of Esther, a knife that was probably used for slaughtering or circumcision, and more,” she explains.

“In his interrogation, he admitted that while he was in Amsterdam he lived according to the Jewish faith. The documents also include the conclusions from his investigation in 1650.

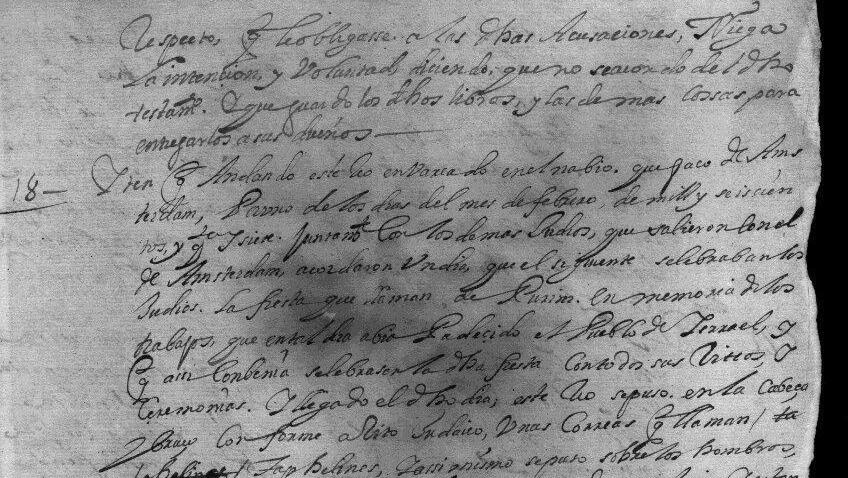

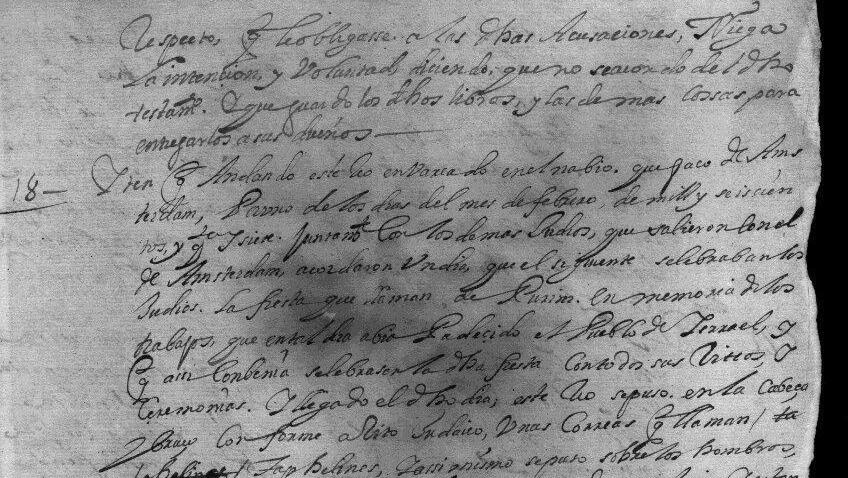

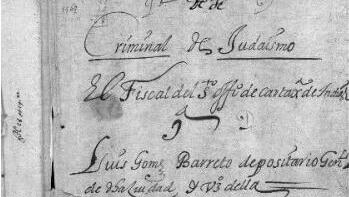

5 View gallery

Page taken from an Inquisition interrogation in 1650

(Photo: National Library of Israel Archives)

“While I find it odd that he would travel to a place where he knew the Inquisition could locate him easily, his documents state that he ‘repented,’ implying that he confessed to the crimes attributed to him and was punished.”

Moreno explains that in 1653, the Inquisition in Cartagena de Indias decided to release Luis Chaves after he confessed and declared his intention to return to the Christian faith. While the document states he was punished, it isn’t clear in what way.

Was it possible to appeal the Inquisition’s decisions?

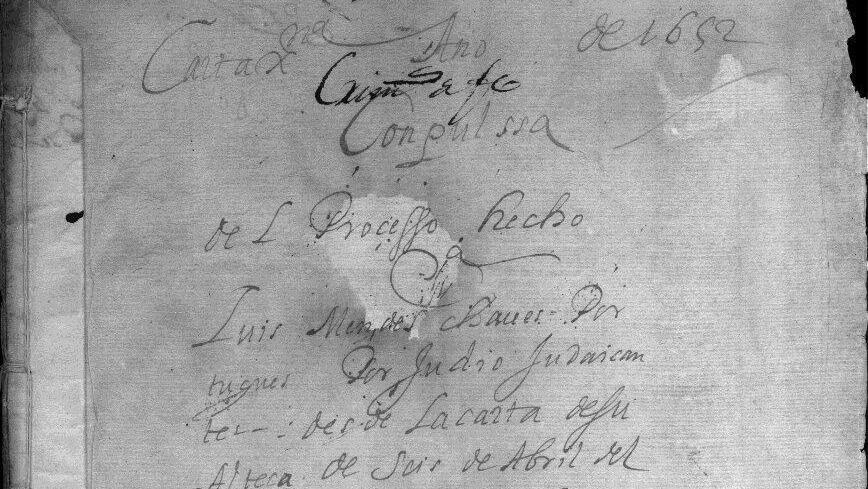

"One of the cases mentioned in the uncovered documents was that of Luis Franco, who was tried in 1626. The court found him guilty and ordered his property to be confiscated, so he appealed the ruling. The second trial took place in 1648, and the appeal was accepted, but only after 22 years have passed."

Dr. Moreno says she was surprised to find that about 10% of the "white" population in these areas of South America were of Portuguese descent. "This likely means they were descendants of Jews. They had a significant role in shaping the colonial society of the period in areas of trade and culture.

“There are even testimonies of how some of them had social connections with Christian Inquisitors and the local elite."

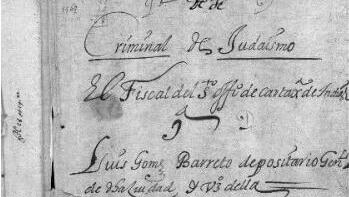

5 View gallery

Page taken from an Inquisition interrogation in 1636

(Photo: National Library of Israel Archives)

Could this explain why Jews weren’t allowed to leave Portugal like they could in Spain?

"Yes. After Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, many of them moved to Portugal and immediately integrated into the local life and the economy. The Portuguese could not afford the economic crisis that would occur if the Jews left, so there was no real intention to allow them to do so, and so they were forced to convert instead."

When did most of these interrogations take place?

"The vast majority of interrogations of Jews took place during the 17th century. Unlike the Inquisition's usual modus operandi in the Iberian Peninsula, in the 15th century, there weren’t many cases of Jewish executions in the Americas.

“In most cases, the accused confessed and received severe punishments including expulsion, confiscation of property, and sometimes corporal punishments, but few were executed."

How was it that the inquisition didn’t pursue the American natives who practiced polytheism?

“One of the goals of the Spanish conquest in South America was a religious one, and they brought priests in order to convert the local populace. Once the Inquisition was sent to make sure everyone followed the Christian law, the local clergy demanded that they maintain the connection with the natives, blocking the Inquisition from persecuting them.”