Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Fentanyl patches for 200 NIS ($60), packs of Percocet tablets at 450 NIS ($140) and drug dealers on Telegram who'll quite happily supply all these drugs to minors - there is a new disturbing "trend" developing among the country's teens.

An ever-increasing number of teenagers throughout the country, from all sectors of society have become addicted to opioids and a wide variety of prescription painkiller medication during the COVID-19 pandemic. They talk about their desire to escape the depressing reality; how easy it is to fool the doctors to obtain legal prescriptions and the double lives they lead as high school students and addicts. This is a pandemic within a pandemic.

"The first time, it didn't make me feel good. I threw up. Gradually, as the pill kicked in, I started feeling really good. I felt a huge sense of optimism and euphoria. It also eliminated the anxiety. Also, no one noticed I was wasted. I was behaving totally naturally. I went to school, sat in class. While using, I even made good grades (90+) in my matriculation exams. And no one could tell I was taking pills".

Mikhael (the names of all the teenagers interviewed for this article have been changed), who lives in Holon, was fourteen when he started suffering from anxiety. Believing the anxiety would pass with time, his parents didn't seek professional treatment. As the anxiety continued, some friends from the neighborhood told him they knew exactly what would cure it. They brought him a tablet of Oxycodone ("Oxy"), an addictive prescription opioid painkiller.

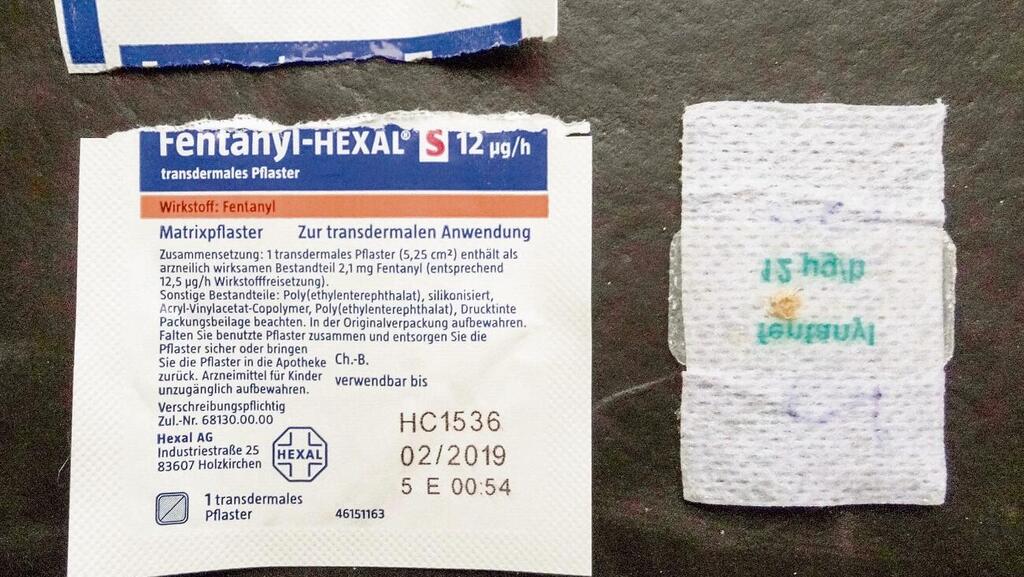

It's been four years since the first pill, but for Mikhael - who's become addicted to the pills – it feels like twenty years. As time went on and the effect subsided, he increased the dosage, starting to use stronger opioids, such as "Fenta 100" patches, containing Fentanyl, a powerful painkiller a hundred times stronger than Morphine. The patch, only legally obtained with a doctor's prescription, is designed as pain relief for cancer patients and patients suffering from especially chronic pain. When the patch is placed on the skin, the substance is released gradually, infiltrating the blood system, relieving the pain. Some teenagers, however, heat up the patch and sniff the fumes.

"The patches were my favorite. That's where the serious addiction started. After a year on Oxy, I moved onto Fenta. The dealer offered me a patch for 200 NIS ($60). He cut me off a quarter for 50 NIS ($15). To economize, I cut up that quarter into tiny pieces as it's really strong anyway. I sucked it and rubbed it on my gums. A small piece was all I needed. It was fun and the high was really strong".

How many teenagers around you use opioids? "A lot. And younger than me. They're all into the patches and Oxy. Some do the patches at home, some outside. I used to like walking around the streets and letting the feeling of optimism take over. When you're under the influence, you feel that everything's fun. So you're sitting in class, chewing a patch."

How much were you spending while you were using? "Something like 200 NIS ($60) a day for over three years. It was hard getting hold of the money, so sometimes I worked in sports and clothing shops. I was high there too."

Mikhael continues to describe his own experiences, reminiscent of a scene in the TV series "Euphoria" which gives a glimpse into the endless range of emotions and drugs in the lives of Generation Z, dealing with loneliness and alienation. At the worst point of his addiction, he recalls how he needed a whole patch a day, as well as three tablets of Clonex, a prescription medication designed to treat anxiety and depression.

As with any addiction, as substance tolerance increases, the euphoric feeling, which initially leads to the addiction, declines. "At the time, I felt that this was the end for me. You're in withdrawal submerged in a huge depression, with horrific symptoms. You can't close your eyes, even if you're tired. You feel terrible - nausea, vomiting - you feel no hunger, nothing, just pain all over your body."

Mikhael isn't alone. Teenage opioid use has itself become a pandemic. It's not a marginal or a dangerous trend threatening at-risk teenagers anymore. "It's all because of COVID," is what we kept hearing from the teenagers that we interviewed for this article. It happens daily both in the center of the country and the outlying peripheral areas, both sides of the Green Line, both in struggling communities and the high schools of more prosperous towns such as Ramat Hasharon.

Last month, the parents of twelfth graders at the Rothberg High School in Ramat Hasharon were notified by the school administration that there had been a "sharp increase in student use of drugs in general, and of prescription medication in particular." A letter sent to parents emphasized that the use of soft drugs was almost routine among students in all age groups, but this time, the story was completely different and significantly more dangerous."It has recently come to our attention that there is heavy use of opioid painkillers (i.e., Morphine, Oxycodone, Fentanyl, etc.) They look like prescription medication which can be swallowed or sniffed," said the message.

Rothberg High School administration also identified COVID as the primary factor exacerbating the situation. "Drug use is in no way new, but like with so much, COVID has made it worse."

Just as the pandemic increased alcohol consumption and drug use among adults, it has affected teenagers looking for a way to escape reality. Some claimed that if it was prescription medication, it couldn't be dangerous, as it was medication sold in pharmacies rather than a drug sold in kiosks. As these opioids, however, come with no medical supervision, the results can be as fatal as street drugs.

Seventeen-year-old Nir from Beit Shemesh found out the hard way. Exactly two years ago, as the pandemic broke out, he started experiencing anxiety attacks. "I was looking to escape, to silence the anxiety and to just be calm. I gradually moved on to painkillers."

How did you get into painkillers? A friend introduced me to Percocet (a forceful painkiller containing Oxycodone and Paracetamol) that he'd gotten from another friend who was taking them. Apparently, his father had a prescription. Then, I had four months of high usage; I'd pop a Percocet and slap on a Fenta patch. That would give me a few days of feeling great."

When do you take opiates? With friends at parties or generally alone? "You do coke to get a party going. Opiate painkillers, you take for the euphoria, to submerge yourself in an ocean of goodness, to get into your own zone, to a life that's not real. It takes you away from all the bad things in the world. It also lasts longer than any other drug. Cocaine is a few minutes and that's it. Opiates are strong. Their euphoria isn't psychedelic, it's very real. It's just sitting around, or not doing anything at all, or walking around the streets, simply feeling free, being yourself. I remember sitting on the sofa during lockdown with my friends, putting a patch on my leg or my arm and giving myself a couple of days of doing nothing, just gazing at Netflix."

Were you aware of the dangers of using opiates? "I thought the Percocet, the Oxy and stuff like that was medication. When I started taking them, I thought it must be better than street drugs, because it's not actually a drug. It's medication." I thought to myself that if a doctor can prescribe Percocet and it gives you a high, it must be fine to take. Back then, I didn't understand that there's no difference between doing this and doing a line of heroin. I can tell you that any teenager, when they start, thinks just like I do and they don't understand what these pills can do to you."

Do you know anyone who became addicted legally? "A friend of mine had a traffic accident when he was seventeen and he was prescribed Percocet and became seriously addicted to it. He ended up in Malkishua (Addiction Treatment Center). He suffered withdrawal symptoms... he was in pain and he really did need to take these pills, but he didn't know they were addictive. No one explained to him that if you become addicted to these painkillers, you'll end up worse off than people doing coke, psychedelic drugs or crystal meth. When you become addicted to Percocet, you can't get through to the person. It's the worse addiction there is. Like heroin."

Like many teenagers, Nir resolved that it was too late. "I did a Fenta patch that was on my leg for a few hours. When I took it off, I went in withdrawal (DT's). I vomited for six hours straight. I knew that if I took even one more pill, it would only be bad for me. You reach a point where you say to yourself: the only thing I have to live for is the patch."

How widespread do think it is? "Some people only take it if someone gets hold of some - for the euphoria. And then there are the addicts, but it's like that everywhere. Especially Percocet and Oxycodone. Most of my friends have taken opioid painkillers at least once or twice. Anywhere you'll find teenagers, there'll always be a few who are into it."

When he thinks about why it spread around him, Nir is very single-minded: "It's all because of COVID. Kids are struggling with difficult mental health situations and in this uncertainty, teenagers are looking for some kind of variety. Even if you're not looking to escape from anything, boredom only brings trouble. What's there left to do when you're at home all day, except for watching Netflix and taking drugs?"

The opioid family has a number of sub-groups, the primary being opiates. Although the best-known drug within this group is heroin, it's not the only one: Morphine, Oxycodone, Percocet, Fentanyl patches are all forceful painkillers of the opiate family.

To relieve pain, opiate painkillers work directly on the nervous system and affect central parts of the brain that control feelings, but the side effects can be horrific: breathing difficulties, nausea and constipation, as well as physical symptoms such as stomach problems and total destruction of the immune system and psychedelic symptoms including anxiety attacks, psychosis, depression, grouchiness and decreased motivation. Overdosing can be fatal – ask any American friend about the catastrophes these drugs can cause.

The light-handedness with which these medications were distributed in the United States led to the opioid crisis, a national calamity claiming half a million American lives over twenty years. And the youth? According to data provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), one in eight young Americans reported using opioids during their high school years. At least 80% of heroin users in the United States started out with opioids with a doctor's prescription.

Israel, as yet, doesn't have official data, but all the experts we spoke to talked about a marked increase in opioid use during the COVID pandemic. The reason is clear: a new study conducted by the Israel National Institute for Health Policy Research (NIHP) in conjunction with the Maccabi HMO, observed an increase of 200,000 in reports of mental health problems by youngsters aged 12-17, compared to the same period preceding the pandemic. Gender segmentation suggests that the most significant increase is among teenage girls, where the study testified to a 68% increase in reports of depression, 67% increase in eating disorders and a 42% increase in anxiety.

To truly understand what painkillers can do to teenagers, we must take into account that the brain doesn't finish developing until we're in our mid-twenties. During adolescence, many parts of the brain aren't fully developed. These are the sections parts of the brain linked to judgment and delayed gratification. A developing brain is much more sensitive to psychoactive substances and is damaged far more seriously than the brain of an adult, and the ramifications can include decreased memory skills and a variety of topical injuries in the brain.

Anecdotal evidence from teenagers is supported by the medical profession. "A lot of problems start with these substances at an early age," Dr. Dorit Yodashkin Porat, of the Lev Hasharon Mental Health Center says.

"This is one of the most difficult addictions, like heroin addiction. People started using them to get a 'high' and at some stage, the 'high' disappears and they carry on using so as not to experience withdrawal symptoms. As the body gets used to the substance, it requires higher quantities to achieve the same effect as in the past. And when you don't have the substance, you feel very unpleasant withdrawal symptoms that make you feel that you need it. People become focused just on getting hold of the substance. All their activity, their whole day, is centered on this. They don't care about anything."

How has the pandemic affected opioid use? "From my fieldwork, I see at least a 50-60% increase in the use of opioid painkillers among teenagers. It's become very easy to obtain through the Telegram app. Because COVID has brought with it a lot of emotional difficulties, in relationships with friends and parents, isolation, depression and loneliness, some teenagers see taking these substances as a means of easing emotional pain. If a teenage girl feels that, during the pandemic, she's lost her social circle, that others are meeting up and she's not - and it doesn't matter if it's true or not – she'll sit at home and develop all sorts of self-image issues and her feeling of self-worth which may manifest themselves in the form of eating disorders or anxiety. We see also increased use among children considered normative, good and stable kids, with two functional, working parents. These aren't kids from troubled backgrounds. These are kids who, before the pandemic, suffered no significant functional problems."

Why do they turn to drugs rather than to psychological support when they feel troubled? "It's important to remember that waiting periods for an appointment in the public health system are very long. For youth and children, it's about six months, which for a child with problems right now, is irrelevant."

"The painkillers are really popular, like weed," declares Or, a Haifa 12th grade student. The excitement over weed has gone down for teenagers who are looking for other ways of getting high. It's a very difficult time. We're not getting what we need. Our parents have their own stuff, and kids are just looking to find themselves. And this drug is easily available. I personally know someone who was hit very hard by painkillers and patches, but it made no difference to his friends. They kept taking it because they're just looking to escape somehow".

Nineteen-year-old Maya from Jerusalem also wanted to escape and it was almost fatal. Giving us this interview from the Villa Balance Addiction Rehabilitation Center in Saviyon, she now describes her life as a "miracle".

"When I was sixteen, I tried Percocet for the first time. A friend of mine from the neighborhood introduced me to it and it made me feel good immediately. I had just had an accident on my electric bike and I needed a metal implant. My arm really hurt a lot and I also wanted some more of the euphoria that I'd already tasted… so I'd tell the doctor that I was in pain from the metal implant and he'd automatically give me a prescription for 5mg Percocet. And it continued. I carried on claiming I was in pain. I played every trick in the book just to carry on getting the prescription and he even increased the dosage. I eventually went up to 10mg – the strongest dosage there is. I was taking ninety pills a month – which is a lot!"

How easy was it to get the doctor to increase the dosage? "It was very simple. I'd call him and say 'It's not enough. I’m still in pain. We have to increase the dosage'. And he would."

At any point, did he warn you of the dangers posed by these pills? "There was one time he muttered 'what's it gonna be?' and that was it."

After a full year of using Percocet, Maya was introduced to a yet more dangerous opiate: Fentanyl. "I didn't really understand how crazy it was. When I saw that I could get a prescription for it, I said "OK. let's give it a try"."

How did you convince the doctor? The transition from Percocet to Fentanyl is a serious step. "I simply told him that the Percocet wasn't helping me anymore and was giving me constipation."

Maya effortlessly got her hands on the drug with the doctor's permission, completely legally, getting in deeper and deeper, to a place of possible no-return. "I remember one friend always telling me 'Never try the patches'. So, curiosity got the better of me, and I did want to try. At first, the doctor prescribed me three 12mcg patches – each patch was supposed to last for three days. I would stick it on or smoke it. I'd remove the adhesive, put it on silver foil, carefully heat it up from underneath and inhale the fumes with a straw. Doctor's orders were to stick it on my body, but the substance releases very slowly, so to get high, I was simply smoking it".

It must be emphasized - with correct, time-constrained use and under medical supervision, Fentanyl patches and other opioids can give relief to patients suffering from pain. This, however, isn't the story here. Maya was sniffing the Fenta fumes, asking over and over again to increase her dosage. She'd often finish sniffing all her Fenta before the month was up. "I went up from three 23mcg patches to ten 25mcg patches. For the rest of the month, I'd get sorted through friends with pills or other opiates. I got to the stage that I couldn't get through the day without some kind of opiate."

And then came the day that Maya almost lost her life. "I was sitting at my friend's house. I was doing a patch and I had a heart attack," she recalls with a humiliating look. My friend called for a mobile intensive care unit and the next thing I remember was waking up in the vehicle after they'd resuscitated me. If I'd been on my own, I'd have died that day. It was a miracle."

The Health Ministry has very clear regulations, stipulating that opiate painkillers should only be given to youngsters in especially acute circumstances, such as following an operation or suffering from extreme pain and even then, they should be prescribed for a limited time period and under close medical supervision. Maya's sad tale shows how, on the ground, sometimes the very opposite happens and the ease with which teenagers can get their hands on fatal drugs seems unbearable. Following conversations with friends for whom it's worked, teenagers arrive at their doctor's appointment very well prepared. So, although there's no real medical justification, they get the opioids without any great effort.

Eighteen-year-old Chen lives in the Samaria region. Unlike Maya, she didn't need to have an accident or have any kind of pain to get a doctor's prescription. "I knew about drugs from the time I was very young. At thirteen, I was smoking weed. Aged fifteen, I was hanging out with friends when a friend brought a Fenta patch. I instantly liked the clarity from the tranquility it brings… that the world stands still... everything's quiet and you don't have to make any effort or do anything. I, very quickly, managed to get a prescription for it. I'd buy patches at the pharmacy".

How did you get a prescription? "I just made up stories for the doctor. I told him that I had chronic back pains. They did a few tests on me, but I exaggerated everything. I knew that for certain kind of pain, I'd get what I wanted".

How did you know what kind of pain would get you a prescription? "Friends told me. I knew that this guy or that guy had got a prescription. Fourteen to seventeen-year-old kids. One guy had a prescription for patches, another for cannabis. No problem."

Did anyone say to you "It's addictive, be careful"? "No. No one warned me".

By the time Chen was sixteen, she had prescriptions for Fentanyl. It started with a 25-mcg dosage, sometimes six patches a day. She was using it for two years. It just escalated.

Didn't you have to renew the prescription? "I renewed it every six months with no difficulty at all, sometimes through my family doctor, sometimes through a psychiatrist, sometimes through a back clinic. I put on a show and I was sorted. And if I was in withdrawal because I hadn't done a patch in a couple of days, then that was the best show ever, because I really was in enormous pain and I made them believe that my back was hurting.

"Two years into this, I realized that I had a real problem. I started freaking out, my body felt unsettled. The clarity and tranquility had disappeared and any time I wasn't high, I felt I was going crazy. I couldn't breathe. And then when I was high, my mind was coming up with nonsense and I came up with all sorts of delusions about myself. I felt I couldn't go on, that any moment, I'd find myself in Abarbanel [Mental Health Medical Center]".

Where did the need to block out your feelings come from? "When I first got to Villa Balance, nearly two months ago, I just thought I'd need to do the physical withdrawal and that would be it. As time goes on, I see that, although the physical withdrawal and rehabilitation are very hard, that's the easy part. Home was very problematic; my parents got divorced. The home disintegrated - my mother and five siblings all broke down. Everyone was crying all day long. I couldn’t be sad about the divorce. It broke me. It had always been very hard. There was never any physical violence, but my parents argued all the time and there were always rows at home. I think this was the main thing that drove me to use drugs... the painkillers gave me what I didn't have at home – some peace and quiet."

How did you get up and take yourself to rehab? "What saved me was the desire to become a mother. When I started losing it, the thought of being a mother hit me hard. I said to myself: 'What are you doing to yourself? What kind of mother are you going to be'? I realized I wouldn't carry on living like this for much longer and what kind of mother will I be if I don't make it to 20?"

Although teenagers have found ways to fool the system, the drugs are readily available anyway. It's often a friend or relative who gets the opioids, which are very popular prescriptions in Israel. Clalit, Israel's largest HMO, issued 115,000 opioid prescriptions in 2013. Four years later, in 2017, the same HMO issued 116,000 such prescriptions – a 45% increase. The trend is similar at Israel's other health funds.

"At the end of the day, it's all about availability," says Nir. "If a friend's father had a slipped disc, there'd be opiates in the fridge, so we'd immediately try and get our hands on them. The moment someone got a packet from their parents, we'd finish them off immediately".

Even when dealers received our message presenting ourselves as a seventeen-year-old girl, they had no problem supplying the goods. A pack of five Fenta patches sells for 300 NIS ($100) and a pack of twenty 10mg Percocet pills sells for 450 NIS ($140). A pack of 20mg Oxycodone pills goes for 400 ($125).

"Teenagers don't see this stuff as drugs," says Ilan (like the youngsters interviewed for this article, speaking under an assumed name) who, working in the educational system, has seen opioid abuse up close. Echoing what we've been hearing from the teenagers, Ilan tells us: "This is something we haven't seen before. It's new. The kids are getting the drugs from Telegram or prescriptions from their parents, and they're teaching one another what to say to the doctor to get a prescription on their own. As young people's problems have increased during the pandemic, prescriptions are being written quite freely. Teenagers are ingenious enough to do their homework about exactly what they need to know and precisely what to say exactly to the doctor to get the drugs."

Which sector of the community is in danger? Are there identifiable characteristics? "We see it at all levels of society, from high-flying students through to special-ed kids and drop-outs. It's the whole spectrum. The pandemic has turned everyone into at-risk students," he says.

The vicious cycle caused by opioids is especially cruel because it's so hard to get out of it. Withdrawal symptoms are particularly harsh, including horrific muscle pain, constant flu-like symptoms, diarrhea, muscle contractions and endless shivering. "I've never seen withdrawal lasting less than five months," says Dr. Irena El Or, psychiatrist specializing in narcology.

"Like withdrawing from heroin, this is also a chronic addiction – and to get to remission, totally retreating from the illness, after years of using is very difficult, especially for young people. Invariably, I have no choice but to transfer withdrawal patients from painkillers to Suboxone or Methadone (prescription medication designed to reduce the pain of withdrawal from opioids) and only when I see some kind of stabilization, do I start decreasing the dosage of the alternative medication. Patients often stumble on the way, even if they do have supportive homes," she adds.

"Yes, you can get out of it, but addiction is a problem they'll have to learn to deal with their whole lives," explains Dr. Yodeshkin Porat. "The temptation to go back to using will be there for their whole lives. At Lev Hasharon Mental Health Center, we've been running an outpatient ward for teenage addicts. It's Israel's first, and sadly the only, such ward in the country. We need units like this throughout the country.

What advice would you give concerned parents? "Be very, very vigilant, try to create an open dialog as much as possible, as youngsters have numerous layers of denial and lies around their usage. It's important to allow for open discourse, offering them help as much as possible."

Is there any real way for a parent to catch it in time? "Watch out to see if this kind of medication is disappearing from the fridge, or if their teenager is going to various doctors, asking them all for a prescription for pain medication, pay attention to changes in behavior, if they shut themselves off, start stealing or if their functioning level or general interest seems to decrease, or if their regular group of friends suddenly changes."

Mikhael has been clean for two weeks. Ever since his parents discovered he was using, he's been undergoing psychiatric treatment and has been prescribed Suboxone. Nir, six months clean, also sees a psychiatrist, takes psychiatric medication and also has a prescription for medical marijuana. Maya, clean for two months, is participating in a structured rehabilitation program, and Chen has been clean now for two and a half months.

Their real struggle, however, has only just begun.

The Health Ministry said in response: "Prescription opioid medication addiction is known and the ministry has been working for several years towards its eradication. We have established an executive committee discussing what steps to take to improve response. We are unaware of purchasing medication via family doctors. We plan to operate with the professional bodies to publish a platform on the matter, dealing specifically with teenagers and young people.

"In light of the information that you have presented, we will add to the inspection questionnaire for HMO family doctors, specific questions pertaining to youngsters. We will focus on increasing doctors' awareness concerning teenagers and adolescents."