The guest who stayed in Room 337 at the Sharon Hotel, located on the shores of Herzliya, captivated the hearts of the receptionists, waiters and housekeepers. "He's a true gentleman and very pleasant," said the hotel receptionist to Yedioth Ahronoth reporters Shaul Nakdimon and Nachum Klieger, as the unusual guest piqued their journalistic curiosity.

Read more:

Those were days of security calm that the Israeli public yearned for, following the end of the Six-Day War, and the Israeli summer was cheerful and tranquil. Shortly before that, the book The Godfather by Italian-American writer Mario Puzo had been released, later serving as the basis for a famous film trilogy, the character of the charismatic gangster captured the imaginations of Israelis.

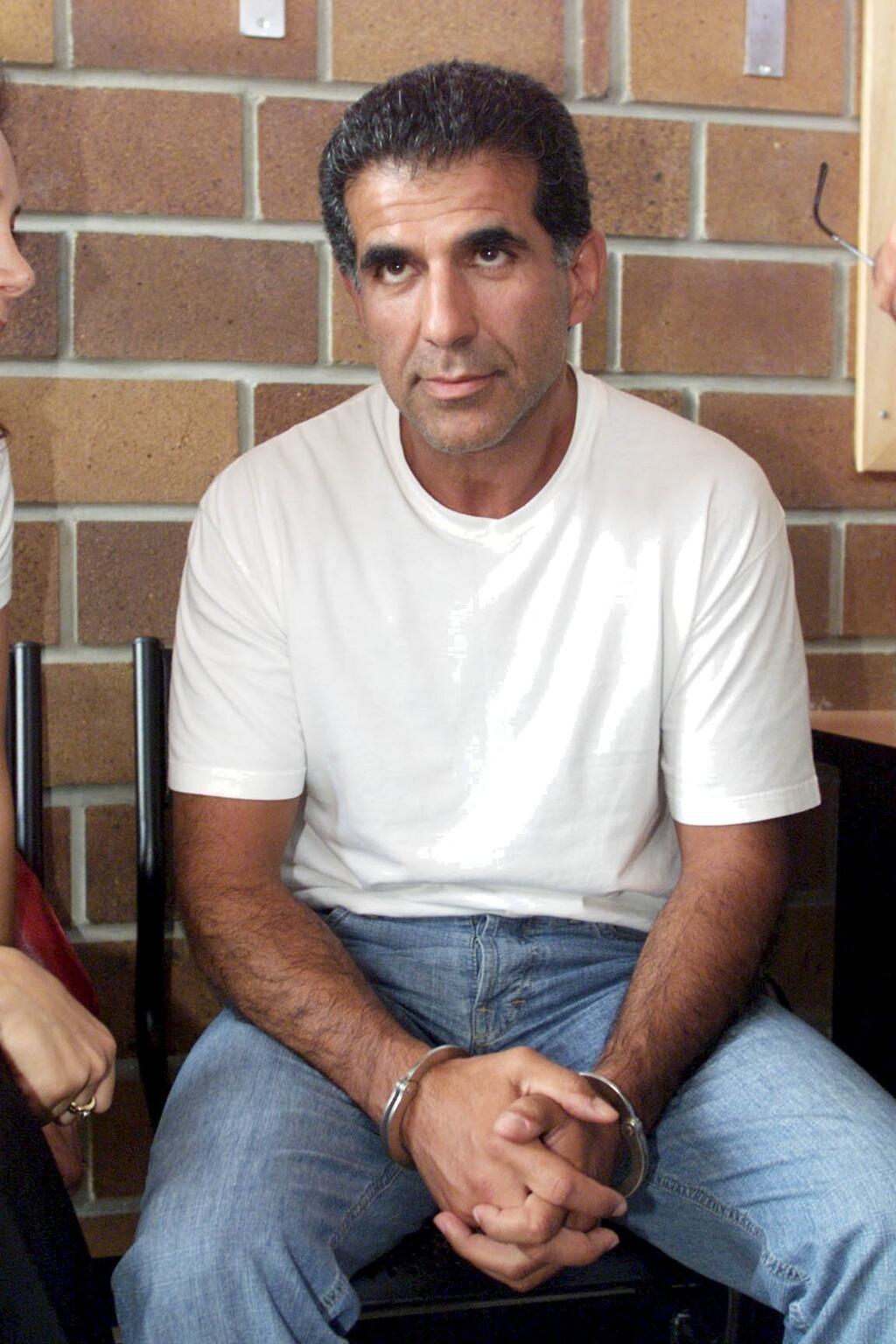

The guest, an American Jew named Meyer Lansky, came to Israel to explore the possibility of settling in the country. However, the praises he received from the hotel staff did not align with the views of the American authorities about him.

In the United States, Lansky was considered one of the top organized crime bosses and a gambling kingpin. Together with his partner, New York mobster Bugsy Siegel, he was a founding figure of the grandiose Las Vegas casinos.

Lansky even reached out to then-interior minister Yosef Burg, with a request for Israeli citizenship, but it was rejected out of concern that he would bring his illicit dealings to Israel and use the country as a refuge from his legal obligations across the sea. Lansky appealed to the Supreme Court, but the judges rejected his case, and he returned to the United States, much to his chagrin.

Meyer Lansky’s deportation did not save the young country from the clutches of organized crime. On the contrary, the early 1970s marked the establishment of hierarchical criminal groups with organized operational mechanisms, led by charismatic, violent and ambitious leaders. The hunger for vice among the local here, be it gambling, drugs or prostitution, was no different from that of American citizens, and organized crime flourished.

For many years, the police ignored all hints and evidence pointing to the existence of organized crime. Committees were formed on the subject, and the media extensively reported on criminal organizations operating in various areas of the country, such as Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, Jaffa, Bat Yam, Ramla-Lod, Netanya, Haifa, Pardes Katz, Ramat Amidar and more.

The main areas of activity were drugs, protection rackets, gambling in Israel and abroad, human trafficking, usurious loans and more. Cautious estimates spoke of billions of shekels rolling under the noses of the authorities each year.

At a certain stage, the country woke up, set aside the debate about the existence of organized crime in Israel, and the war began. Today, with organized crime in Israel being an undeniable reality, and the police finally cracking down on it, it is time to outline the milestones of this industry that affects the lives of each and every one of us.

From the individuals who founded it, through the charismatic figures who led it, its victims, the state's denial of its existence and power, the transformations it underwent over the years, and up to the realization and understanding that organized crime indeed exists in Israel and that it is time to deal with it using all appropriate means.

There are too many prominent figures to list them all. The field, which for some reason is perceived as sexy by the public, contains within it a lot of bloodshed, pain and terror. We are talking about people capable of killing a 17-year-old boy simply because he witnessed a murder, or disposing of the body of a person whose family desperately wants to know his fate, all for the sake of money.

A murder like in the movies

On the night between April 6 and 7, 1970, Ezra "Shem Tov" Mizrahi left an unauthorized casino on Tel Aviv’s Hayarkon St. and headed toward his car which was parked on Allenby St. Suddenly, a man approached him, and from about 50 feet away, he pulled out a 9mm pistol and shot him in the abdomen.

Mizrahi, known as the "king of the underworld" of the Shapira neighborhood in southern Tel Aviv, fell to the ground, clutching his stomach. The man approached him, put the gun against his head, and fired four more deadly shots. Mizrahi's companion, who was with him, was also shot.

The killer began to flee, and a group of soldiers who witnessed the murder chased after him until they caught him. The shooter was Solomon Abu, a French immigrant, who according to suspicion, imported the operating style of European criminal gangs. "It was like in the movies," testified an eyewitness in Abu's trial, who was convicted of double murder and sentenced to two life sentences. The motive for the murder was a dispute between the two over protection money.

This event finally brought to the public's attention the existence of an underworld in Israel. The murder was the opening shot for a series of 13 articles published by journalist Ran Kislev in Haaretz newspaper under the headline "Organized Crime in Israel." "The most denied thing in the country is the existence of organized crime in Israel," Kislev opened the first article in the series, which was published on April 15, 1971.

Ran Kislev's comprehensive investigation described a situation in which organized crime operated in Israel in general, and in Tel Aviv in particular, in most types of crime. At its forefront were individuals with extensive connections, including figures from the ruling party, the IDF, as well as official authorities such as the municipality and the police.

Kislev named the prominent figures of the Israeli mafia during that period, including Mordechai "Mentsh" Tsarfati, YIsrael Danokh, Yaakovle Cohen, and others - comparing them to both the recognized bosses of international organized crime, like Al Capone, and the fictional ones, like Don Corleone from The Godfather.

"Until this series of articles, no one defined organized crime in Israel," notes Avi Davidovich, a criminologist and former deputy head of the international investigations unit at Lahav 443, popularly known as the “Israeli FBI,” and a walking-talking encyclopedia on crime in Israel.

"We know that criminal organizations existed before that. For example, during the days of austerity of the 1950s, there was a thriving black market around prohibited goods like eggs and poultry. We also know that this market flourished under an intensive mask of corruption, with officials of the authorities benefiting from it."

In 1967, the Six-Day War broke out, followed by the War of Attrition. In the early 1970s, between the impressive victory of the Six-Day War, the conclusion of the War of Attrition and the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War, a certain calm prevailed that allowed society to focus on itself and internal issues.

"During that period, the Black Panthers (a protest movement of Mizrahi Jews against discrimination) emerged, and various scandals came to light. This atmosphere, together with the success of the book The Godfather, laid the groundwork for the publication of the report claiming the existence of organized crime in Israel," elaborates Davidovich.

"What is most astonishing is that despite such noticeable differences in background and conditions, the image reminded me of the famous American mafia," Kislev summed up his groundbreaking report.

"Even here, the organization is based on a constant connection between 'families' - or, more precisely, factions. The operational realm includes prostitution, extortion, gambling and smuggling. The power base lies in the number of soldiers each faction's leaders can mobilize on one side, and the opportunities to influence people in high positions on the other."

Kislev added and wrote, "There is also a significant difference. The economic power of the organization in our small country is far from the immense power of the mafia. Another difference: although it already exists for several years, the Israeli organization is still in its early stages. It is possible that today it can be easily eliminated. But it is also possible that in a year or two, we will reach the situation that American society has reached: the mafia in the United States can’t be eliminated."

"The authorities immediately went on the defensive," Davidovich recalls. "Because, in fact, the findings of the report indicated not only the failure of law enforcement in dealing with organized crime but also allegations of corruption that spread among its ranks. In other words, not only are you impotent - you are also partners in crime." Police spokespersons worked extra hours to deny the allegations raised in Kislev’s reports and blamed the situation on a "lack of resources."

Nevertheless, then-justice minister Yaakov Shimon Shapira ordered Attorney General Meir Shamgar to examine the allegations raised in Kislev’s report. Shamgar's report was submitted to the government in September 1971. Its conclusion: there is no evidence of organized crime in Israel. The police felt relieved, the government returned to its affairs, the media shifted its focus to a series of deadly terrorist attacks that occurred in the mid-1970s and only the criminals went on with their business unabated.

The birth of a criminal

Rahamim “Gumadi” Aharoni was born in the Hatikva neighborhood of Tel Aviv in 1939. In the 1960s, he moved to live in the nearby Kerem HaTeimanim neighborhood, where he met Tuvia Oshri, and the two were considered leaders of the Kerem HaTeimanim faction, engaged in various criminal activities.

They also established the Bar Bakar meat factory, which later served as the disposal site for the bodies of Amos Orion and Ezra Cohen, a duo of criminals who demanded "compensation" for the prison sentences they claimed to have served after they covered for the charismatic leaders of the faction.

However, prior to that, during the years when the term "organized crime" was practically unheard of in Israel and gangsters were considered mere movie characters, the underworld grew and consolidated its power, spreading its influence over the Tel Aviv metropolitan area.

In 1976, three years after the disastrous Yom Kippur War, the security situation was relatively calm, and Operation Thunderbolt to release Israeli soldiers from Entebbe restored some national pride. Once again, attention could be turned to internal affairs, and the issue of organized crime resurfaced with another series of articles, the work of journalist and writer Avi Valentin, published in Haaretz in August 1977.

"For the opposition, the issue of organized crime was an excellent tactical asset in their battle against the government. The concept of 'organized crime' carried not only the meaning of threat and danger that needed to be warned against but also sort of an indictment against the executive authority for negligence and collusion"

Valentin recounted, among other things, the exploits of Oshri and Aharoni. He described the police's incompetence in detail. In one of his articles, Valentin quoted a police officer who told him, "The police are not built to deal with crime at this level. We need to produce results. We cannot investigate for three months without making arrests. That's why we focus on the 'small fish.'"

Davidovich states, "Back then, they didn't use the term 'organized crime,' but rather 'gangs' and 'groups.' Mapai was still in control, and the person leading the fight against organized crime and corruption was a young Likud lawmaker named Ehud Olmert. For the opposition, the issue of organized crime was an excellent tactical asset in their battle against the government. The concept of 'organized crime' carried not only the meaning of threat and danger that needed to be warned against but also sort of an indictment against the executive authority for negligence and collusion."

The bombshell that shook the Israeli underworld, rocked the public and completely changed the perception of organized crime in Israel, was published by Valentin in March 1978. It was the infamous "List of 11," which became one of the most prominent symbols in the history of organized crime in Israel and perhaps the most significant milestone in recognizing the existence of organized crime in our small country. The explosive name may give the impression of a "most wanted list," but in reality, not all those listed are necessarily the leaders of criminal organizations.

- Mordechai "Mentsh" Tsarfati

- Bezalel Mizrahi

- Rahamim “Gumadi” Aharoni

- Tuvia Oshri

- Eli Tisona

- Ezra Tisona

- Yehezkel Aslan

- Yaakov Epstein

- Rafi Shaul

- Munia Shapira

- David Dzanashvili

"In retrospect, not all the names included in the 'List of 11' had to be on it," recalls Hezi Leder, one of the document's authors, who at the time was the head of the Tel Aviv Police Intelligence Department. "The document itself did not list the crime bosses in Israel. It was a list of individuals who we believed had acquired assets through illegal means, and the goal was to prompt the tax authorities to start building cases against them. At that time, those were the people we dealt with. We were at the beginning of the road, and I admit that things we saw might not have been as we thought."

Leder, who joined the police force in 1975, does not hesitate to honestly speak about those "innocent" days when the police did not understand what was brewing beneath their noses—and maybe didn't want to know. "We need to start from the assumption that when we talk about the end of the 1970s, police procedures were completely different. But criminal behavior was also vastly different."

In what way?

"First of all, there were no mobile phones, no computers and no Facebook. The wiretapping law did not exist yet (it was enacted in 1979 and, among other things, allowed for recording conversations with the consent of one party). The majority of the information that reached us came from informants who cooperated with us. So they came to us with all sorts of stories, and some of them were bullshit. We worked both in Israel and abroad, and the truth is we didn't achieve great success. The police were also cautious about stating that there was organized crime."

How were the criminals different?

"There were many groups operating in specific areas. There was no organized crime in the sense of a criminal group controlling a specific territory. The control was more fragmented. Additionally, there was less violence. There were no assassinations, no shootings on the streets. There were no explosives under cars. In essence, it was different."

Valentin, who still guards the source that leaked the list to him, explains to Ynet how it came into being and how it reached him. "In February 1974, an explosive device went off outside the door of the head of the Tax Authority, Eliezer Shiloni. I had just returned from the Chinese Farm (the ground of one of the fiercest battles against the Egyptian army during the Yom Kippur War). I went to meet him, and he told me about organized crime. I returned to the newspaper and started working on it.

"In the meantime, Shiloni met with Moshe Tiyomkin, the commander of the Tel Aviv District Police, and asked him to prepare a list of individuals suspected of accumulating wealth through criminal means, so that they could be targeted for offenses related to income tax, similar to the method used to bring down the American Mafia boss Al Capone. As a result of that meeting, this list was prepared by the intelligence department of the Tel Aviv District Police."

So who actually leaked the list to you?

"I won't say. I'll just say that the decision to release it wasn't made by one person. I worked for months to obtain this list. I made personal contact with someone. The list was handed over to the tax authorities only months after it was written, solely because I published it."

What impact did it have on organized crime?

"You're still asking me about it thirty-odd years later."

Weren't you afraid to deal with these people?

"I was young. Only 26 years old. Complaints were filed against me with the police, and they stalked my girlfriend. Rahamim Aharoni and Tuvia Oshri talked to me. They were not happy. We met at a restaurant in Kerem (HaTeimanim), and they cornered me in such a way that I couldn't leave. I felt very uncomfortable with them in that meeting. Gumadi was nice, but Tuvia was mean. He was violent. From the tone of his speech, you could understand his aggression. They were threatening."

Murderous blood feuds

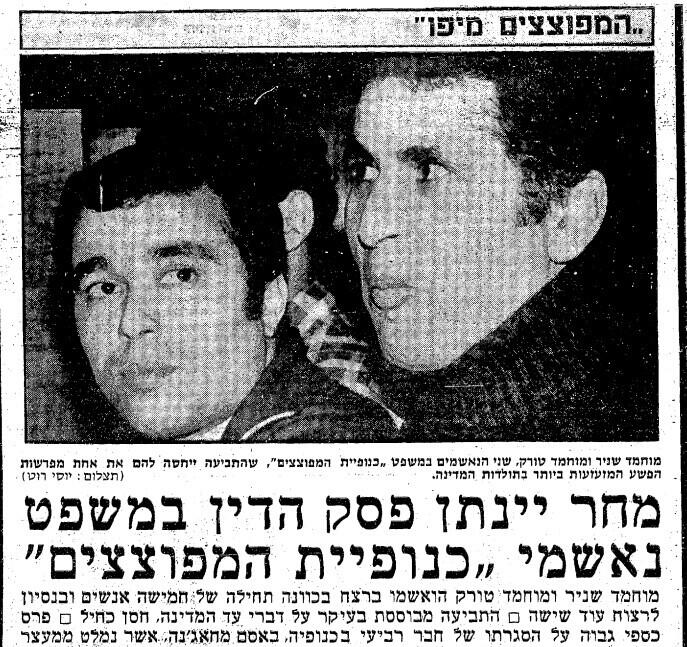

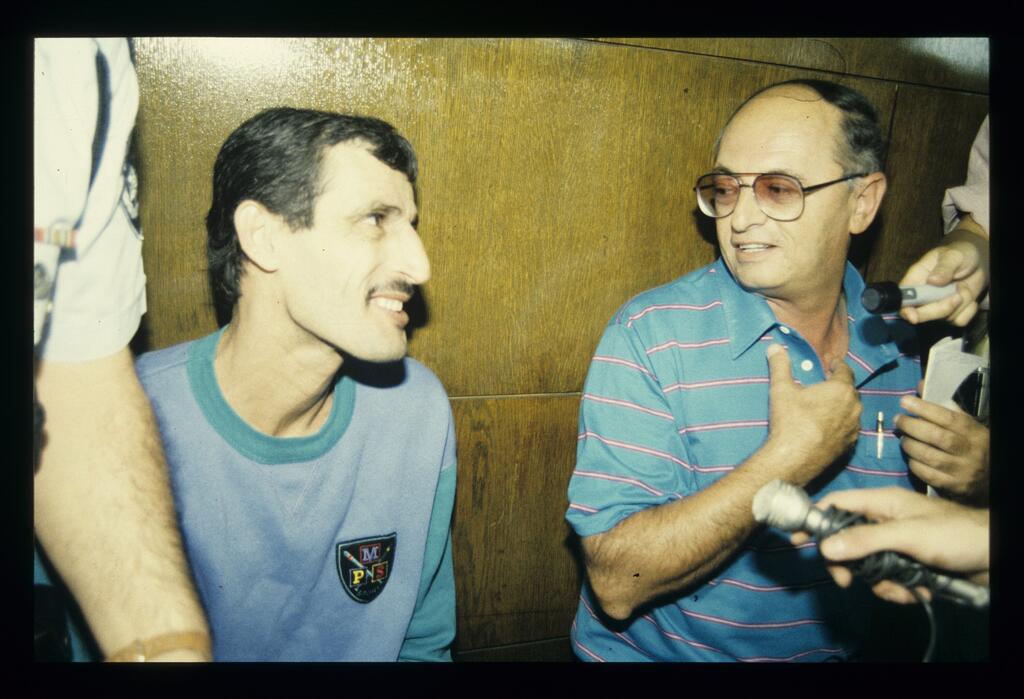

In July 1978, Yehuda Edri, a 32-year-old resident of Bat Yam, parked his car in Jaffa. Within a second, a powerful explosion shook the entire street. Edri died on the spot. It was the opening shot of one of the bloodiest feuds in the history of organized crime in Israel. The conflict erupted between two crime families involved in the drug trade: the Arab family led by Ali Abdullah Shinir and Muhammad Hajj Khalil from Jaffa, and the Jewish family led by Edri from Bat Yam. The former earned the dubious nickname "The Bombers' Gang."

The response to Edri's murder did not take long. In October '78, a booby-trapped grenade exploded under the car of Muhammad Hajj Khalil, injuring him moderately. It turned out that the assassination attempt didn't go smoothly, so another attempt was made in July 1979. Assassins opened fire at his store in Jaffa. Edri's brother and others were arrested and stood trial for this murder, but they were acquitted due to lack of evidence.

The assassination of Muhammad Hajj Khalil was not the last act of revenge for Edri's murder. In August '79, assailants broke into the home of Ali Abdullah Shinir in Jaffa and beat him to death with an axe, along with his wife, children, and a witness who passed near the scene.

Fortunately, the others were only injured. From that point on, a bloody and murderous spree began, claiming many victims, including a young couple whose car exploded while they were placing their two-year-old daughter in the booby-trapped vehicle. The daughter was injured, along with six other passersby.

After an intensive investigation, two suspects were brought to trial, aided by the recruitment of Hassan Khalil, a key figure in Muhammad Shinir's gang, who was a central player in the organization. Shinir, the head of the gang, received convictions for murder and was sentenced to 12 years in prison, of which he served two-thirds before being released.

Two years after his release, he murdered his brother, his brother-in-law and Police officer Ofer Cohen before committing suicide. His deputy, Muhammad Turk was convicted of serious offenses, including two counts of murder, and was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Thus, the 1980s began in Israel. "If there was a criminal decade, with the highest crime rate, it was this decade," says Davidovich. "Israel was already in the era of organized crime."

This time, the government authorities began to show signs of awakening. The conclusions of the Shimron Commission, headed by former attorney general Erwin Shimron, were prompted by the series of articles by Avi Valentine.

The commission determined that there was organized crime, but it was of an "Israeli nature." This was supported by a court ruling in a defamation suit filed by Bezalel Mizrahi and against Valentin and "Haaretz," in which Mizrahi emerged victorious. However, the judge determined that the defendants "proved the existence of organized crime in Israel."

According to Davidovich, "The late 80s and early 90s were characterized by a wave of immigration from the Soviet Union. And then something interesting happened here. It was actually the police who coined the term 'Russian mafia.' In this case, there was no problem acknowledging the existence of a mafia because it came from abroad. It's not like we allowed it to flourish. But it did serve as a reason to demand additional resources. Some defined Russian crime as a 'strategic threat' to Israel. However, if we map out the criminal organizations in Israel, we won't find any Russian organization there."

One of Israel's veteran criminal lawyers, who represented many prominent criminal figures, talks about the transformations that took place in the field during those years. "The 80s and 90s were characterized by top criminals carrying out the crimes themselves. The generation of crime bosses like Shmaya Angel, Herzl Avitan, Morris Algarisi, Yaakov Shemesh and even Yitzhak Abergil in his early years—all of them were hands-on individuals.

"There were rivalries because everyone wanted to be on top, but it wasn't yet organized; each node stood on its own. There were local organizations, like the Pardes Katz and Ramat Amidar gangs, but they still weren't organized crime organizations in the classic sense of the term.

"One of the colossal failures of this period was the prison system, which placed the 12 most notorious criminals, known as the 'Daring Dozen,' in a single wing—the Rakefet Wing in Nitzan Prison. They created an aquarium of crime. During those years, being a state's witness was like crossing the most dangerous lines, and anyone who considered himself a 'man' in the world of crime would never become a state's witness. They definitely had their codes of conduct. They knew how to show respect."

The lawyer tells a story about a former client of his, one of the most prominent criminals who operated here in the 70s and 80s, a killer whose name is known in every household in Israel.

"One day, when I visited him in prison, he asked me to deliver something for him to someone from his cell, which was prohibited. Some drawing. I told him, 'I won't do such a thing.' So he said to me, 'You know what, because you said no, and I know you're honest, I'll hire you.'"

According to him, "Over time, the nodes realized that they couldn't keep going to prison every Monday and Thursday. Instead, they needed a 'security belt' of operatives, drivers and guards, so that if one falls, they can replenish the ranks. And then, slowly but surely, an organization emerged, and as soon as it marked its territory, another node established its own organization.

"Each one started building its own center, which essentially ensured their survival. While personal rivalries existed before, now a situation of rivalries between organizations arose. Crossing the lines to join another organization symbolized betrayal.

Of course, once you harm members of another organization, reprisals begin between the organizations. Violence escalated in an atmosphere of lawlessness. Such an organization also needs a budget. There are expenses, like any organization. So they started getting involved in businesses like bottle recycling and other means of funding. The pioneers of the system were names like Abergil, Rosenstein, Avutbul and Alperon. Even in the Arab sector, they began to understand the principles."

The wars between the organizations became bloody. In June 2002, Yaakov Abergil, the brother of Yitzhak and Meir, was assassinated, shot outside his home in front of his wife and children. In August of the same year, Felix Abutbul was murdered in a shooting outside his casino in Prague. Yaakov Alperon was assassinated in November 2008 in a car bombing, and so on. Innocent civilians also lost their lives. In 2008, Margarita Lautin, a 31-year-old resident of Yehud, was murdered in front of her husband and infant daughter during a failed attempt to assassinate the criminal Rami Amir.

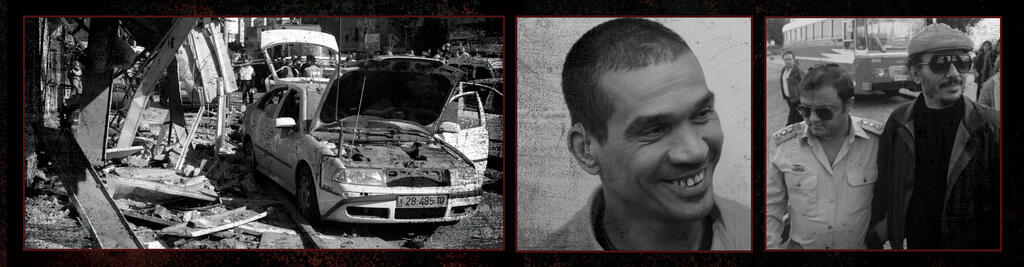

However, the defining event of Israeli organized crime occurred in December 2003. A powerful explosion shook Yehuda Halevi St. in Tel Aviv. Those days were the peak of Palestinian terrorist attacks that claimed the lives of many Israelis. The first police officers to arrive at the scene found three dead bodies - Naftali Magad, Rahamim Tzruya and Moshe Mizrahi - and dozens of injured individuals, initially assuming it was another such attack.

However, when they discovered that one of the injured was a bodyguard of the criminal Ze'ev Rosenstein and that the explosive device was placed above the door of his favorite currency exchange office, they realized it was an underworld assassination attempt. The country was horrified, and authorities were ready to wage a relentless war to permanently dismantle the criminal organizations. The investigation into the bombing and the subsequent legal proceedings against the culprits later became known as Case 512.

The case that changed everything

It is impossible to discuss the history of organized crime in Israel and the rise of these organizations without mentioning the Trade Bank affair. Eti Alon, the bank's employee, executed a colossal embezzlement between 1997 and 2002, amassing an astronomical sum of a quarter billion shekels. The theft was carried out on behalf of her brother, Ofer, who was addicted to gambling and used the stolen money to pay off his debts, thereby providing funding to the criminal organizations, led by the Abergil family, and contributing to their empowerment.

"In the early 2000s, the Israeli authorities finally began to realize that they could not continue like this, and that instead of these idiotic disputes over the existence of organized crime, they needed to do something," says Davidovich.

"The Trade Bank affair left the criminal organizations in a state of luxury and growth. The bombing on Yehuda Halevi Street, which Commissioner Aharonishki called the 'Felons' Park Hotel,' was a turning point. It should be remembered that after the bombing at the Park Hotel, Israel launched Operation Defensive Shield."

The turbulent 2000s marked the onset of another Defensive Shield-like operation in the war against organized crime. In 2000, the Anti-Money Laundering Law was enacted, and in 2003, the term "criminal organization" was finally enshrined in Israeli law. The Organized Crime Combat Law was enacted, defining a criminal organization as "a group of people, whether associated or unassociated, operating in an organized, systematic and continuous pattern to commit offenses."

The law imposes a ten-year prison sentence on the leader of a criminal organization and mandatory forfeiture for those convicted of activities within such an organization. In 2008, the Witness Protection Authority and the police's Lahav 433 unit, the IDF's combat unit against organized crime and corruption, were established. This unit has also led the infamous Case 512 for years.

In the 2000s, the Tel Aviv District Police Intelligence Department investigated several murder cases and assassination attempts within its jurisdiction but with limited success. The turning point came in late 2011 when an Israeli arrested in Brazil began cooperating with the police, providing detailed information about violent events. He later became a state witness, and he was not the only one. In total, five individuals from the organization testified behind bulletproof glass in the Tel Aviv District Court after signing an agreement with the state.

In 2021, after decades of violence and crime, 18 years since the murder of three innocent people and following six years of trial, the Israeli criminal world reached a catharsis.

In an 824-page verdict, the panel of judges at the Tel Aviv District Court, led by Judge Gilya Ravid, determined that Yitzhak Abergil headed a ruthless and murderous criminal organization. He was charged with intentionally causing the deaths of three individuals in the 2003 bombing on Yehuda Halevi St., the attempted murder of his rival Ze'ev Rosenstein and a long list of other offenses.

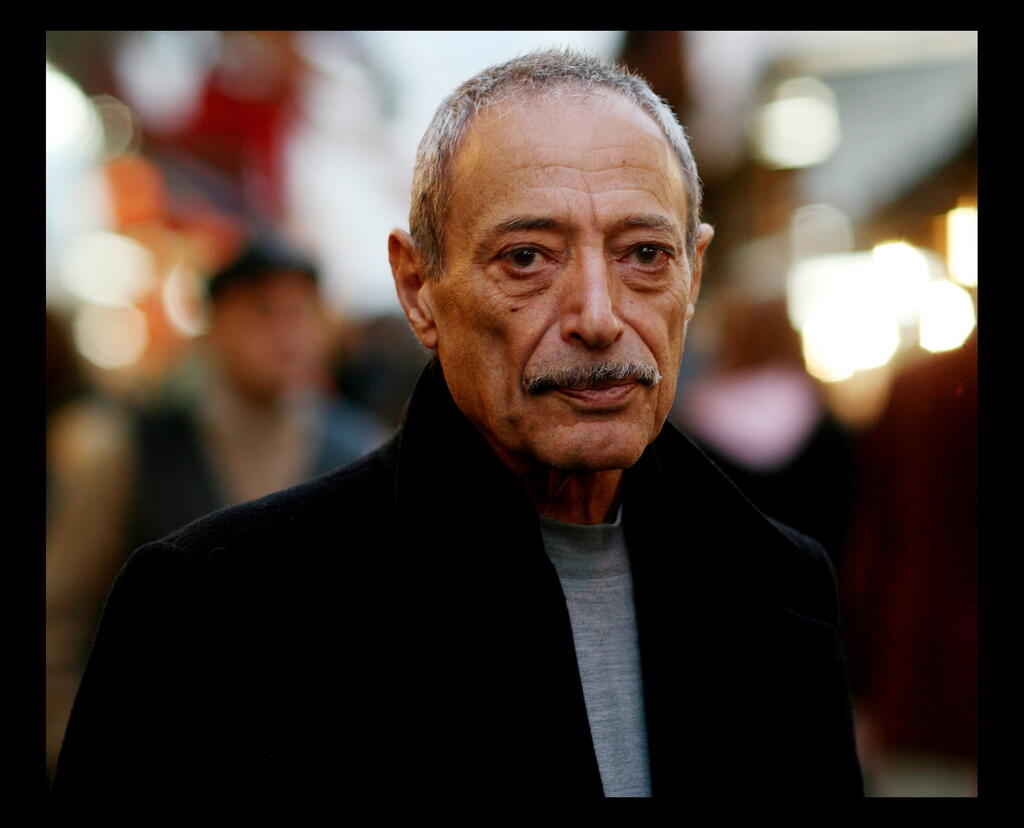

Reading the verdict tells the complete story of an Israeli criminal organization. Abergil stood, directed, organized, controlled and supervised the members of the organization. "The gray life of a submissive worker in a factory, the workplace to which he was assigned after his release, did not satisfy his personality and aspirations for admiration, money, honor and publicity," the judges wrote.

During those years, he sought to establish himself as a leader in the criminal underworld and, for that purpose, instigated a bloody internal struggle against those he perceived as his enemies and those allegedly involved in the murder of his brother, Yaakov. Thanks to his charisma, Abergil managed to recruit many soldiers for the organization, including prominent figures within the criminal groups who obeyed him and engaged in the organization's activities in Israel and abroad. Abergil had direct contact with his subordinates within the organization while maintaining secrecy within its ranks.

"Over the years, Abergil's charismatic and powerful persona strengthened the organization's power and the prestige it gained," the judges said. "Many in the criminal world sought his proximity. Being close to Yitzhak Abergil opened doors in the underworld. This prestige, which also received media attention, assisted Abergil and his associates in establishing connections both in Israel and internationally, strengthening their criminal activities. The organization grew and expanded to become a significant international force operating in various fields: weapons, gambling, drugs and violence."

To fund the organization's activities and solidify its position and power, Abergil operated behind an extensive international network engaged in massive drug trafficking. Abergil directed the organization's economic activities and instructed the use of organization funds for its criminal activities. As part of this, he instructed the managers to transfer organization funds to the operatives in Israel for criminal activities.

The court ruled that although Abergil did not personally carry out the acts, he was guilty of them as the head of the organization. The prosecution's sigh of relief was heard throughout the streets of Tel Aviv. Abergil, 54, is unlikely to be ever released from prison.

The plaintiff's attorney, Nissim Marom, expressed satisfaction, stating, "The verdict is a resounding blow by law enforcement authorities against the criminal organizations that have operated in Israel in recent decades." So, what lies ahead?

Most of the figures mentioned from the world of crime throughout the article are no longer among the living. "They did not reach old age," says Leder. Case 512 dealt a severe blow to organized crime in Israel, but it certainly did not completely defeat it. Today, we can see extensive organized crime activities, for example, in the Arab sector.

So what's next? Where is organized crime in Israel heading?

Davidovich: "Case 512 is an international milestone. It's a once-in-a-lifetime case. We need to create such a case at least once every decade to minimize the phenomenon. In terms of violence, we can see where we stand. In the Arab sector, there is an average of three homicides per week."

"The police now have the necessary tools. They have the authority to protect witnesses on the right side, so they can recruit agents and state witnesses without worrying about future headaches. They have the authority for tax evasion on the left side, and the law banning money laundering, which allows them to 'freeze' assets. So, on the day of the arrest, they can issue seizure orders for bank accounts, apartments, yachts—what have you."

13 View gallery

The aftermath of the assassination attempt against Zeev Rosenstein

(Photo: Michael Kramer)

"And then we see on television those images of seizing BMWs and Mercedes-Benz cars. Beyond the luxury aspect, it's effective. Because if you put the head of the organization in prison, he can still manage the organization. But if you empty his pockets, then despite all his charisma, he's worth nothing."

Leder: "Let it be clear—there is no vacuum. Criminal organizations will continue to thrive here because that's how the world operates. The question is, who will stand against them? Which police force, which prosecution, which judicial system?"

Did Case 512 create deterrence?

"For the classic criminal, there is no deterrence. If that's his way of life, he will continue to act accordingly. Prison is not a consideration for him. It may even have the opposite effect. In prison, a young criminal only strengthens his position and gains experience. No one should have any illusions that this story will ever end."