Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Captain B. lives in an Arab community that is not Israel's greatest fan. So, during her five years of service in various Air Force positions, she’s never gone home in uniform. "I have more civilian clothes in my closet at base than uniforms. Before I go home, I change back into civilian clothes. You can’t imagine the lengths we go to at home. In summer and winter, we wash the uniforms and put them straight in the dryer, never hanging them outside."

Why is that? What might happen if people in your community know what you do?

"Physical harm."

To your family?

"Yes."

And they’d have to leave the community?

"I don’t think there’d be anyone left to leave," she says, with a bitter smile.

Is it that bad?

"I think so. It really troubles me. It’s hard for me. I want to proudly walk around in my uniform. I know I love it, but it comes at a price."

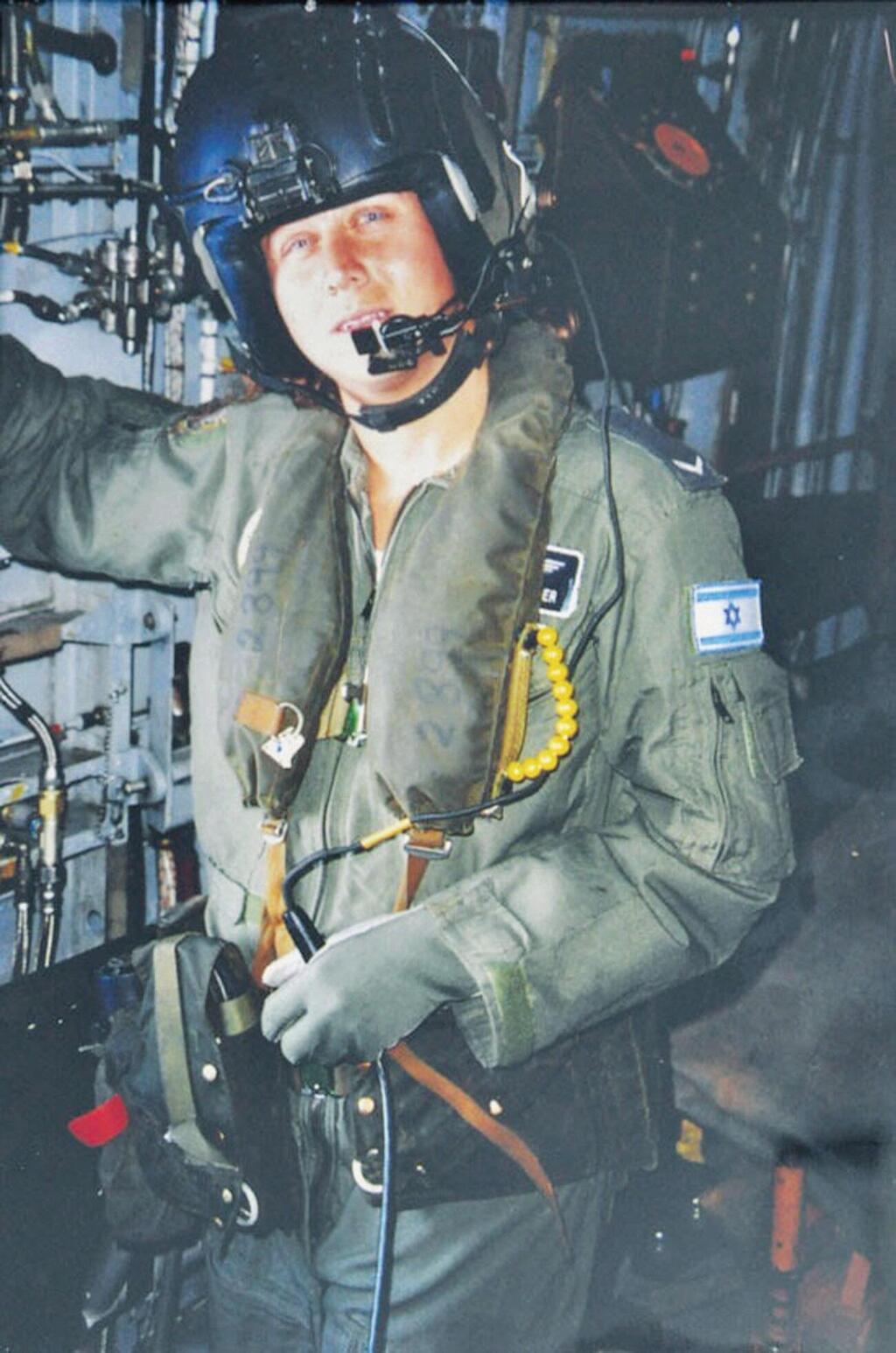

Just as we were about to leave her office for the Black Hawk helipad at the 123rd Squadron where she’s currently serving, something in her suddenly changed. Captain B. stood up straight and couldn’t stop smiling. Donning her flight overalls with a helmet and visor covering the rest of her face, Captain B. quickly climbed onto one of the helicopters to have her picture taken. She clearly feels more like herself around all the helicopters coming and going from the fighting in Gaza, than in the community where she was born and raised.

How long will you keep concealing what you do from your community?

"Recently, there’s been an escalation in hostilities in my community, violent incidents, and shootings. My motto is that although it’s good to die for country, and I don’t care if I'm killed, the thought that something might happen to my family because of me is horrible. I wouldn’t be able to live with it. For me, God comes first, then my family, then the army. That’s the order for me.”

Only on civilian clothes

Three weeks ago, Captain B. became the the first Arab female airborne mechanic in the IDF when she completed the airborne mechanics course with distinction. This isn’t easy for anyone, more so for someone who has to maintain a secret life and a double identity.

When the talented Christian Arab teenager graduated high school with very high grades, everyone in her mixed Muslim-Christian community was sure she’d be studying medicine within six months. However, Captain B. decided to enlist. "I’m fired up in the IDF. I grew up in a home that was always Zionist and always taught us to love the state that provides for us, and therefore we must give back," she said.

"I always knew I wanted to enlist and be part of the people defending the country. And all this even though I could have easily gone to study medicine. My matriculation grades were very high, but after 12th grade, instead of going to university, I went to the IDF recruitment office."

How did your parents take it?

"My parents are perfect," she said with a smile. "They believe in letting their children do what they love. Because I was the first in the family to enlist, there was no one to guide me and tell me about the positions. My mother had heard about the military police, so that’s what I requested. But as my scores in the initial selection tests were so high, I was contacted by the Air Force who invited me to join the IAF Technological College in Haifa. They take people who haven’t studied electronics, and invest two years in which they teach them. Then, when they get their electronic engineering diploma, they join the Air Force’s technical teams. I consulted my mother who said 'Go. Give it a try. What have you got to lose?' So I gave it a shot."

I assume that you were the only Arab there.

"In my first year at the college, there were a lot of terrorist attacks. I was afraid they’d look at me differently, but the truth is that I was received with love by everyone."

This was a big change for you. You came from a very traditional environment to a diverse class with Jews.

"Basically, I grew up in a home with values. Wherever you’ll put me, I’ll keep those values. By us, girls aren’t allowed to smoke or have sex before marriage. I could do whatever I liked and my parents would never know, but if it’s something I grew up with at home, I’ll respect it. I’ve never even smoked a cigarette," she jokes. "Although everyone’s trying to corrupt me on that front."

What do you tell your community?

"They knew I was studying, but no one knew what or where. Obviously, I didn’t come home in uniform."

How hard was it to conceal your secret from your friends back home?

"I cut off contact with all of them, losing years of friendships. For years, I’ve been living this pattern of concealing my life. I constantly have to make up excuses. My only friends are people from the military and when they come visit me at home, they come only in civilian clothes. I’m strict about that."

What about a boyfriend?

"I had a boyfriend for a few good years. Although he wasn’t against my enlisting, when he heard I wanted a combat position, he wouldn’t agree to it. Do you think I cared if he agreed to it or not?”

How did he give up on you?

"He didn’t. It was hard for him. It was a challenge, but we’ve stayed in touch and we’re good friends."

5 View gallery

Search and Rescue Unit soldiers leaving the Black Hawk helicopter

(Photo: IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

Although graduates are generally intended for electronic engineering professions, she began hearing about airborne mechanics during her second year. This is a small group of elite helicopter mechanics who undergo special training after which they regularly join flights. They walk around wearing flight overalls, are considered air support crew, and are responsible for many tasks including emergency repairs in the field, managing the cargo hold in cases of evacuation, and approving landings and take-offs.

A helicopter has two parts, the cockpit and the cargo hold. The pilot is the commander of the cockpit and the airborne mechanic is responsible for the cargo and everything that happens in it.

In the case of the Black Hawk squadrons, the Search and Rescue Unit is responsible for evacuating the wounded and transporting forces deep into enemy territory. Captain B. immediately thought this sounded exciting and decided to give it a try. "Because my Hebrew wasn’t good enough, with my guttural pronunciations, I failed but, as usual, every time I stumbled, I was presented with a better goal.”

Can you give us an example?

During my studies, for example, they told me that they didn’t want me to continue onto the second year 'because I’m an Arab.' I couldn’t understand why and told them that they invited me to join the Air Force. They told me to forget about it and that they’d take care of it. I wasn’t given an explanation."

"In those two years, I represented the college as a minority to guests such as education officials and military personnel. I told them that I was the only Arab student and then they gave me trouble for the following year too. They told me they didn’t want to enlist me because I’m Arab. It’s like they weren’t even sugarcoating the truth. After I completed two years, they didn’t want to enlist me. One of the commanders even told me I could be discharged and keep my degree. I told him that I didn’t want the degree, I wanted the army and they could take back those two years and enlist me."

What did you do?

"One day Gadi Eisenkot, who was the Chief of Defense Staff at the time, arrived for a tour of the college and they presented him with the program's only Arab student. I told him that they didn’t want to enlist me. Within ten days, I was given a draft date. Eisenkot congratulated me when I got my first rank. The college's base commander at the time knew how hard I’d fought to be enlisted and when he awarded me the certificate, he asked to meet my parents. He said to them 'When I saw your daughter standing in front of me at the ceremony, I had shivers all over my body and I shed a tear.' I told him that his saying meant more to me than the degree did."

But Captain B.’s troubles didn’t end there. Most of her class completed their studies and were assigned to various positions in the Air Force’s avionic (aviation electronics) array. This is an advanced and exciting, but mainly top secret, world. Her background didn’t sit so well with some army people. "I was supposed to work in avionic positions and they wouldn’t approve it. They told me I probably wouldn’t get my security clearance," she said.

So what happened then?

"The avionics course coordinator tried to encourage me saying he’d promise to put me in a similar position, as an electrician. So he left with no choice, I did a three-month aviation electrician course and also graduated with distinction. I'm a person who genuinely believes that whatever you do turns out for the best: Now I have certificates both as an electronic engineer and as an aviation electrician. At home, I was taught that wherever they put you, you do your best."

Unstoppable

Although trained as an electronic engineer, B. was assigned as an airborne electrician to the 106th F-15 Squadron. "The atmosphere was good there and so were the people, so I stayed there for three years: two years of regular service and another year as a commissioned officer," she said.

B. was on base during the 2019 November clashes against Palestinian Islamic Jihad in Gaza. "I had to arm the planes sent in there and we loaded crazy amounts of armaments. You don’t really know what it does in the field, but during one of the shifts, after an extensive attack, the pilot returned and came to thank me. He said that his hits were precise and the target was definitely destroyed."

How did that make you feel?

"Full of pride. That's when it clicked about how important my work as a flight technician was. I was already looking to get onto the officers’ training course and I had to get through a special committee because as an Arab, my scores were low. The committee approved me and I qualified as an officer. There were two airborne mechanics in my course who told me that I could re-apply to be an airborne mechanic. That was a dream come true. I fought to get in. But to no avail."

B. was assigned as an officer in the south where she was in charge of one of the maintenance arrays. Throughout Operation Guardian of the Walls in 2021, during the violent riots by Israeli-Arabs, while fighting in Gaza, B.'s situation became more complicated. "At the time my job was to simultaneously monitor a large number of aircraft in a very short time for various squadrons. That whole time, I just kept thinking about my home and my family. The tensions within the Arab communities at the time were not good."

In your community too?

"There were terrorists who came out of our community. There was also shooting and grenades and they spray-painted 'Death to the Jews' on the streets. My commander was afraid to let me go home for the weekend and told me to stay on base."

During this time, her desire to stay in the army and fight for her dream became much clearer. She wanted to become the first female Arab airborne mechanic. She tried again, but her commanders, she said, tried to dissuade her. "They told me there was a great difference between battle and helicopters and that 'you won’t make it.' I told them that if I want something, I get it. When I realized that one of them even gave me a low grade on my reference for the officer’s course, I called to tell my commander, bless her, who was on maternity leave. She angrily called my commander, telling him ‘You won’t stop her from fulfilling her dream and I’m approving her for the course.’ “

Female camaraderie is a beautiful thing but only goes so far. Airborne mechanics usually come from the helicopter's technical array. In the Air Force, these are quite different worlds, almost parallel universes. B.'s commanders understood that the talented officer was unstoppable and opened up a position in the 114th Squadron which was closed the previous year. Now she had the chance to learn about helicopters. "I spent a year there and I was awarded the base's award for excellence."

How do you explain it?

"I have an extremely strong work ethic, like my mother. Over the holidays, our family celebrates until 3 a.m., and she’s at work by six. I’m like her."

Didn’t you have your breaking points?

"During that period, there was one time that I cried and asked myself why I ever enlisted. It was because I felt alone. The helicopters were landing at 2 a.m. and I was back at the squadron the following morning. I needed to show them I was no rookie and I was back at the squadron at 7:30. I needed to show the helicopter crew that there was someone there waiting for them and that the helicopters were landing safely. I am, after all, an officer and if there are any malfunctions, I need to deal with them. So, that week, with sleep deprivation, I asked myself 'Why am I here?' I felt I couldn’t function and I was afraid of making mistakes from being tired and there was no one to help me."

What did you do?

"I called my mother."

Obviously.

"I cried to her and she said to me, 'I won’t hear another word. Get yourself some sick days and come home'".

Did you get yourself sick days?

"What do you think? I stayed right there and pulled myself together. No matter how hard things get, I get up the next day with a smile on my face. I enjoy my work. I wish everyone could do what they love."

"Wake up! Hamas got in!"

Finally, she succeeded and began the prestigious course. She endured eight grueling months, including long hours of studying, with a great deal of fitness, physical endurance, and field training. If a helicopter is forced to land in a hostile location, the aircraft mechanic, as one of the crew, will be forced to navigate in the field, survive, and sometimes fight. B. successfully completed the course and was assigned to the 123rd Squadron in central Israel. Just three months before the end of training, while she was at home on a weekend, October 7 happened.

"My mother woke me. 'Wake up. Hamas got in.' Half asleep, I murmured ‘What do you mean Hamas got in?’ In my mind, all the bases are guarded. She turned on the TV and the first thing I did was text my commander, telling him that although I was in training, I was coming to the base. I wanted to help them with whatever an airborne mechanic knows to do, to feel I was doing my part. I was at the base by 10:30 and ended up staying there for a month, although we were still in the middle of the course.”

Have you seen the Hamas videos? How did that make you feel?

"Yes. I saw them. Horrific."

How did they react to the massacre in your community?

"It’s not that they went out demonstrating or spray painting hate messages outside, but I did see incitement online."

How did you feel when many were actually happy and justified the massacre?

"It’s disappointing. Because when a rocket lands here, it doesn’t distinguish between Arabs and Jews. It kills everyone. I wish they would understand that. But sadly it’s not happening.

Did you get negative reactions from people who know what you do, like from your extended family? Did they call you a traitor?

"Some people said things like ‘You’re using a fighter jet that’s going to attack Arabs.’ I told them I’d prefer one house there (in Gaza) was destroyed, than many here. Because that’s what it means."

How did they react?

"I don’t know. Maybe they didn’t like it, but that’s okay. I don’t care what they think. I believe that house in Gaza, the one the army wanted to attack, contained lots of rockets that could have hit five houses in Israel."

Aren’t you afraid that someone who does know what you do will be tempted to talk about you in your community?

"My uncles who know are keeping it as a secret, to protect me but also because the truth endangers them too. I can tell you that one of my aunts told me she’d never send her children to the army, but if that’s what I wanted, it's up to me. At the end of the day, each person makes their own choice."

Have you been ostracized by family members?

"No. Definitely not. They come to the house, throw me parties when I complete my courses. There’s nothing like it. No one would do that to you because you’re in the army, not Christian Arabs. I even drafted the son of one of my acquaintances."

Do you know anyone who was killed or kidnapped on October 7?

"No, I don’t know many guys in the Ground Forces. Not a lot of us Arabs are serving. Regretfully, I feel, because I believe everyone should enlist because this is the one and only Land of Israel.”

Have you been blamed by Jews about what happened on October 7?

"Nothing. I don’t walk around on the street. People don’t know me. We’re not an exposed family. We don’t stand out. We go from home to work and back. We don’t mix. When people see us in the street, people ask my mother in amazement when she raised the kids."

Many young people in the Arab sector define themselves as Palestinians. How do you define your personal identity?

"First, I don’t believe there’s such a thing as an Israeli who’s also Palestinian. I also don’t know why they define themselves like this. In the Quran, it says Israel and the People of Israel. I define myself as a Christian-Israeli who speaks Arabic. Christians must believe that this is Israel because the Canaanites are mentioned in the Bible."

Would you marry a Jew?

"I have no problem marrying a Jew. I’m not religious, but I obviously wouldn’t convert. Everyone should live with their own religion."

And what does your family think about it?

"I won’t lie to you. My parents are pushing me to be in a relationship. I just always wanted to obtain a profession and be the best at what I do. So a relationship was always secondary for me. In the meantime, I take comfort from my pets.”

Following a great deal of training and exercises, including with the Search and Rescue Unit, with whom the squadron works closely, Captain B. will soon enter the heart of the fighting in Gaza as an aircraft mechanic. “I’ve got butterflies in my stomach. Soon I’ll be an important part of evacuation operations. It's a privilege."

Do you have relatives in Gaza?

"Luckily, no."

How scary is it to enter Gaza in the middle of the war?

"Let me tell you something: I’m not afraid of anything. I truly believe that I can die at any minute. I could trip on my way to the helicopter, break my neck or, God forbid, have a heart attack, so no scenario scares me."

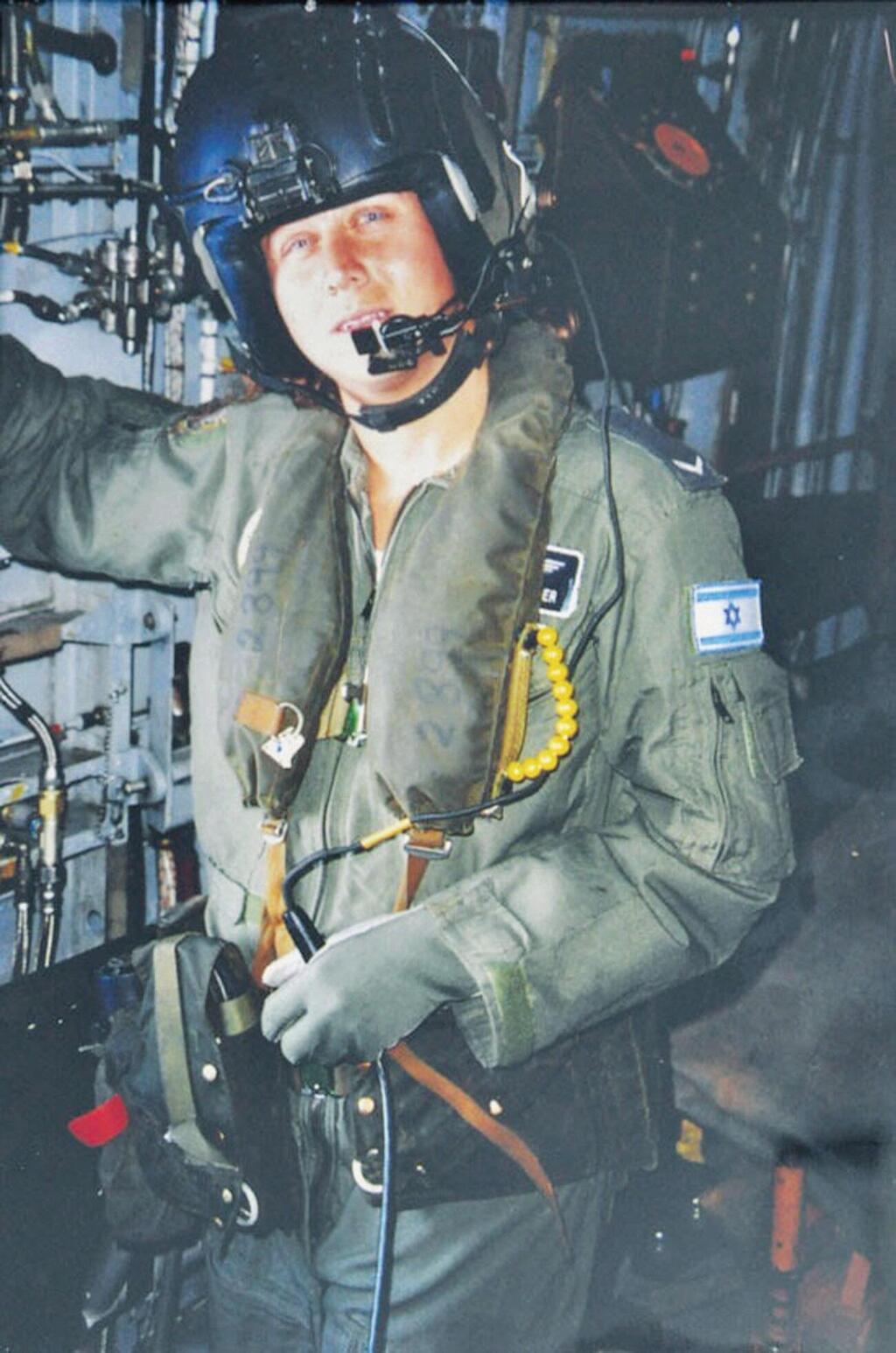

In the Second Lebanon War, the Air Force’s first female airborne mechanic, the late Keren Tendler, was killed as she landed deep in enemy territory. Is this something that crosses your mind?

"Keren? Yes. I’m very familiar with the case. I know that what happened to her could happen to me too. But I can’t keep that thought in my head and let myself be controlled by fear. If I’m afraid of dying every time I get on a helicopter, I’ll be missing my goal. I live today as if I’ll die tomorrow and I don’t care if I die, but the most important thing is that I love what I do and I do the best I can. I’m not afraid. This is how I see life."

5 View gallery

The late Keren Tendler, the Air Force’s first female airborne mechanic

(Photo: IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

What scares you the most?

"I’m most afraid of losing a family member. Other than that, nothing. Honestly."

A combat helicopter was hit by an RPG on October 7 and crash-landed straight into the fighting in a kibbutz, so it’s a realistic scenario.

"Correct. There is that fear, but you’re in a war, so you know you’ll get there, to the battle. And in war, there’ll always be the risk of downing helicopters or God forbid, there could be a technical malfunction in a helicopter. I don’t think about it. First, I look at the reason I went up in the helicopter in the first place, because I know there’s someone wounded in the field. If I went out with the purpose of saving him and I die, as least I did my best."

God forbid, you get captured. In such a situation, you’re in triple danger: You’re in the Air Force, you’re a woman, and you’re an Arab serving in the IDF which they see as the ‘enemy'.

"Captivity is a very painful subject. I know I can be captured, but I can’t live in the shadow of fear. I’m not afraid. I’ll fight with all my strength. At the end of the day, if God forbid it does happen, I’ll take off my overalls and pretend I’m an Arab woman from Gaza. I could kill myself before it happens. As I said, I’m not interested in fear at all. Nothing can break me. Nothing. My mother also thinks so."

What does she think?

"I spoke to my mother about the possibility of getting captured. I asked her how she’d feel when I’m there. She replied ‘It would be very painful for me, but I’m not prepared for 20 people to die to get you out of there'. That’s my mother."

When you land there in Gaza, you can expect to see some very tough things around you, or harming what the army calls uninvolved members of your people. That must be hard.

"True. But other than seeing it for yourself, I don’t think anything can be done about it. It used to be very hard for me to hear about Gazans dying because they’re not all Hamas. But I saw in a video how they train their 10–12-year-old children to cock their guns with their feet because they’re not strong enough to pull them with their hands, then you understand how they have no value for life. They live to die and that’s a shame. It hurts. There are people who don’t deserve to die and they’re the ones who pay the price in the end. Just like our civilians who get hit by rockets.”

So, you’ve made your dream come true. Have you thought of doing the pilots’ training course?

"They wanted to send me to the course, but my parents were against it. They were afraid that I would pose a threat to the state and if I had to abort or something, God forbid, happened to the plane. They said people said it's my fault because I’m Arab. Apart from that, I’m happy because I got the position I wanted and I help the country’s security. Have you seen the helicopter exhibit here?” she asked, pointing to some old helicopters displayed.

What about it?

"So, I’ve said that when I finish my reserve duty, I’ll carry on coming here until they throw me out by force. I want to be buried beneath the helicopter exhibit."