Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Footage from IDF's operation in Hamas weapon factory

(Video: IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

The building to which we were headed did not look different from the other businesses, workshops and residences that were around it. We were in the heart of al-Bureij camp. The area had just been taken over by the 188th Armored Division, but still not completely free of terrorists or gunshots and explosions. Despite the hardships, Col. Or Volozinski, the division commander, is focused on the mission.

Read more:

"Come on in," Volozinski says to me and a small group of journalists who had come to him in armored vehicles from Israel. We entered a one-story building, which is actually a large room with benches attached to the walls. There is also a coffee corner. The place, it turns out, was used as a breakroom for the workers at the explosives factory, which operated in the tunnel below several buildings in the neighborhood.

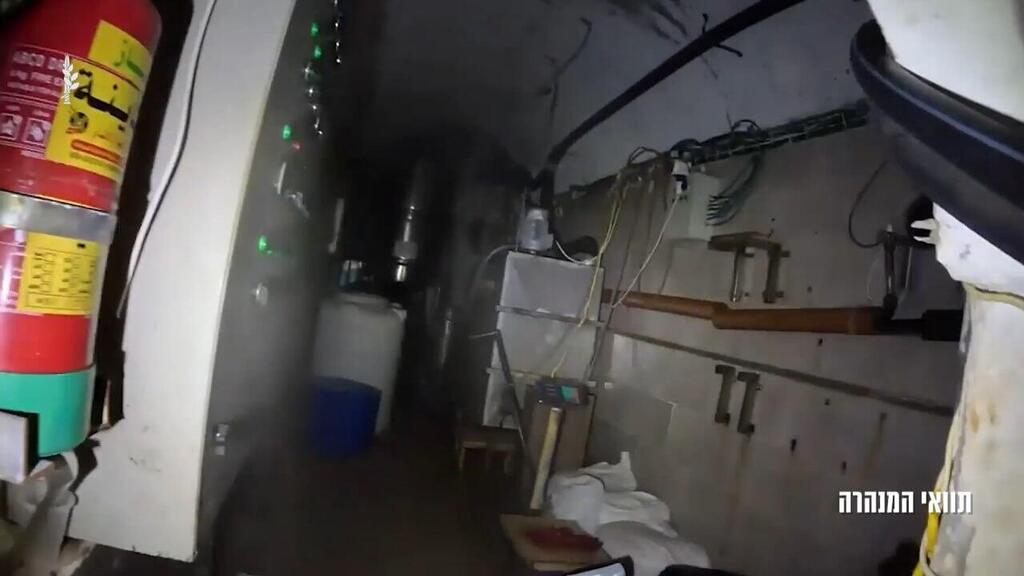

From a side room, stairs lead down to the factory, where Hamas produced propellant explosives for its long-range rockets and heavy mortar bombs. The division commander went down the stairs, and we followed him. A strong smell of ammonia and other chemicals hit our nose. I felt a burning sensation in my eyes.

The entrance of the tunnel is made of reinforced concrete, and it is clear that it should withstand a heavy bombardment and perhaps even absorb a direct hit. On the side throw a white coverall, which was worn by one of the workers who handled the mixing of the chemicals that make up the explosives. He must also have used a gas mask, because otherwise he would not have been able to withstand the acrid fumes that filled the tunnel. Fearing for our safety, we did not go deeper into the explosives production tunnel, and contented ourselves with a peek inside. The reason is not only a fear of breathing poisoning, but because these vapors are explosive. Any spark could produce an explosion, as it sometimes does, despite the precautions the forces take when handling these tunnels.

The IDF spokesman took us to see this tunnel so that we could get an idea of the extent and degree of danger of the military production system that Hamas has developed in several places in the Gaza Strip. The sophistication of the system is evident not only in the products, but also in the location of the various factories - including the underground explosives factory that was underneath to a residential and commercial neighborhood, in the heart of what is known as the al-Boreij refugee camp south of the Gaza River.

This settlement, which is no longer a refugee camp but rather a town with high-rise buildings, is one of the three "central camps" in the Gaza Strip. They are located between the Khan Yunis area, which is south of them, and the north of the Gaza Strip and Gaza City - which is north of them. The factory for the production of explosives is located a few hundred meters from the central axis that runs through the Gaza Strip from north to south, the Salah al-Din axis, whose IDF nickname is the "Tancher axis". This fact is important, because this is how the explosives produced in al-Boreij can be transported Underground to the metal factory - which is also near the Tancher axis. In the metal factory, the iron and steel bodies of the rockets and missiles are cast and produced, in a large hangar above ground.

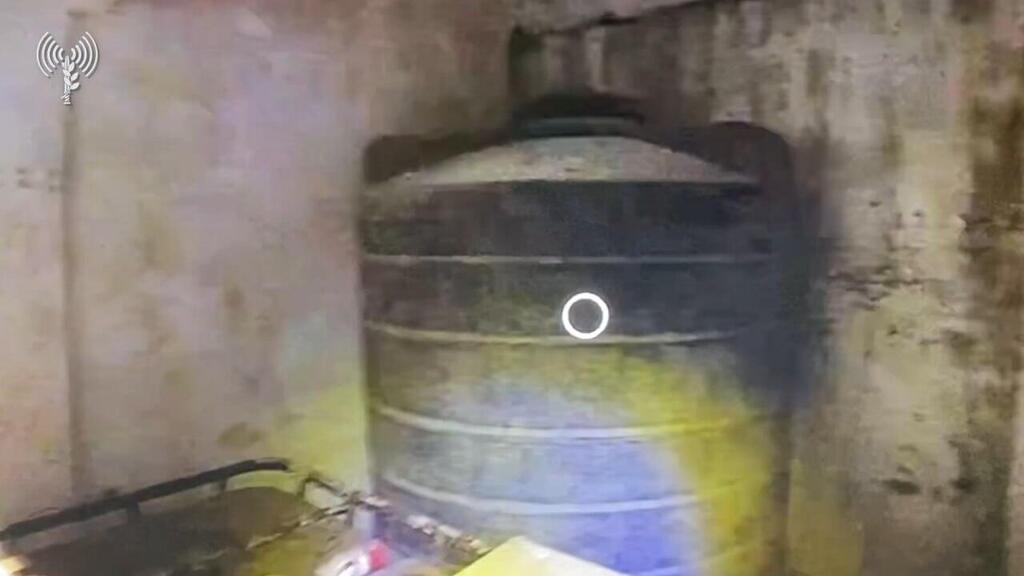

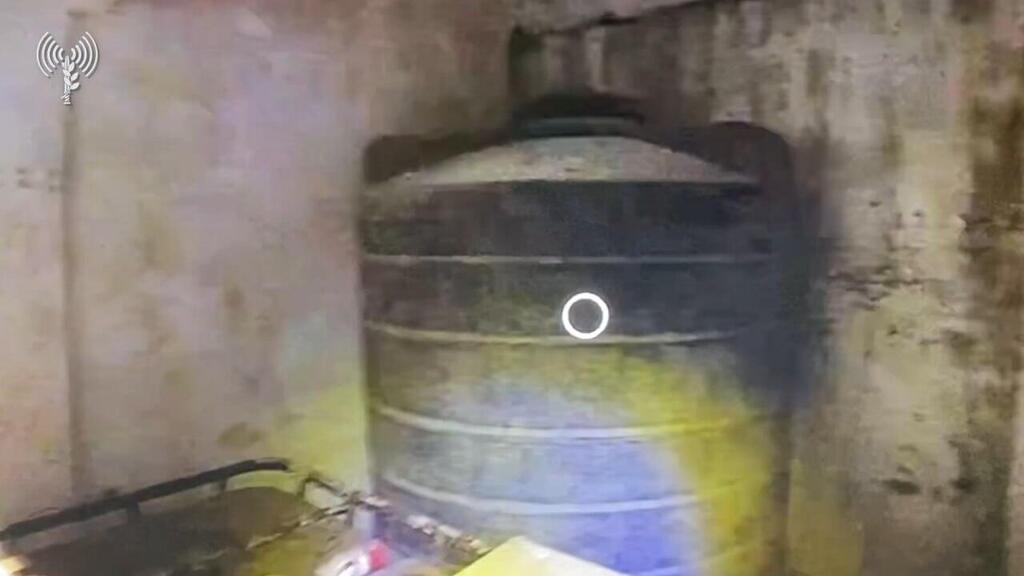

The bodies of these rockets and mortar bombs are then filled with explosives, in a set of underground tunnels under a production shed. The reason why everything related to explosives is underground is that if the Air Force bombs the production site, it will damage the metals but not cause a large explosion - equivalent in strength to several tons of explosives.

This process, in any case, makes it possible to transport and connect all the components of the military that are produced in the area quickly, especially at night and under the protection of the civilian population.

"A perfect array, from the producer to the consumer"

We returned to the APCs. Volozinski, 188th brigade, bid us farewell, not before telling us that the mission in the central camps was still incomplete. The exposure of Hamas's military production system, which he started in al-Bureij camp, made it clear to him how dangerous the terrorist organization is and how much is required to dismantle all of its military infrastructure.

"We knew about this formation and also reached it based on intelligence, but we didn't know how big the underground military industry was," said the division commander.

9 View gallery

Anywhere underground there is a cache of weapons or a production site

(Photo: IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

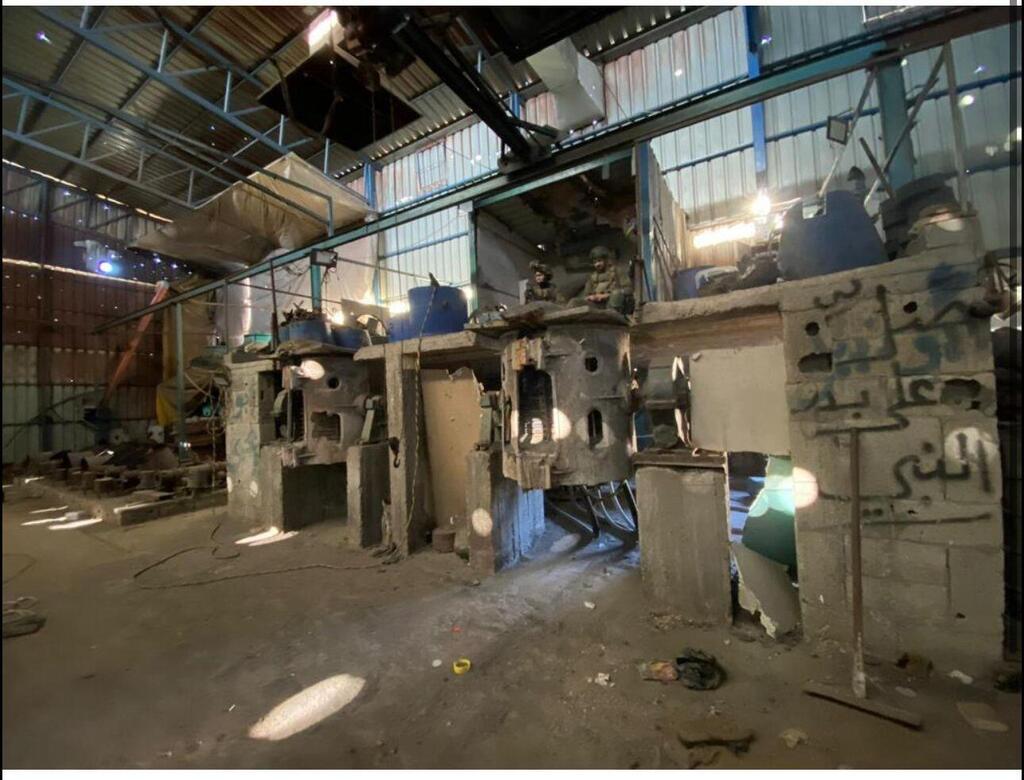

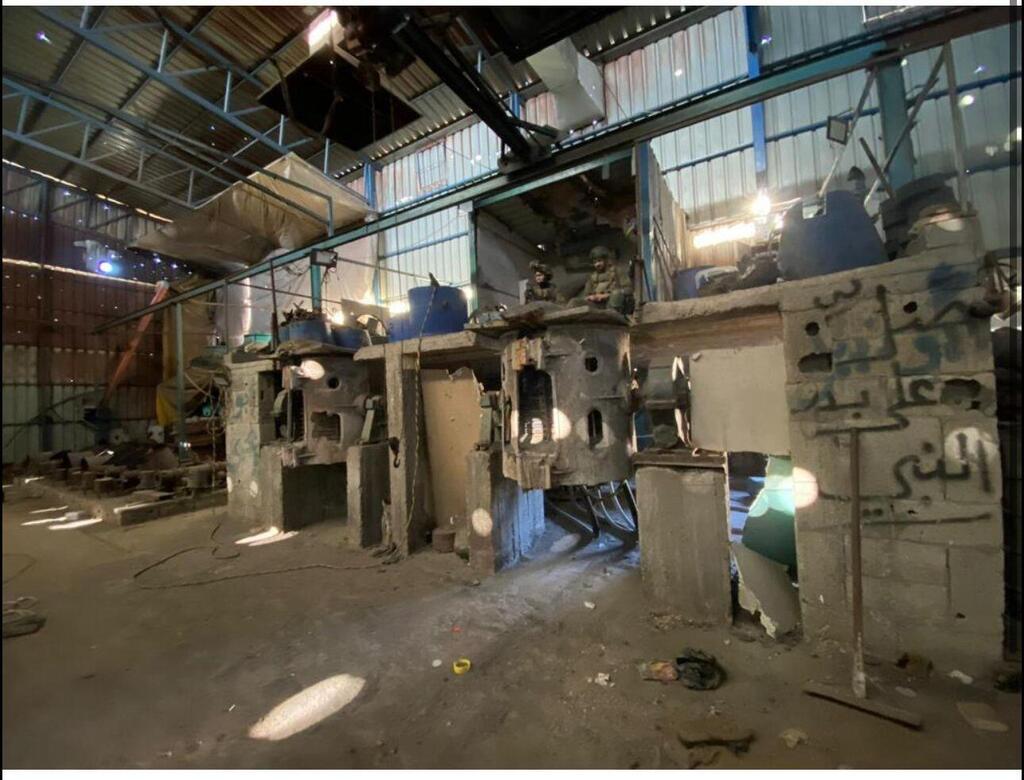

South of there, in the Al-Maghazi refugee camp which is the southernmost of the three camps, we entered a large shed. Actually it was a tall hangar made of a steel frame. Sheets of tin and asbestos serve as its roof and walls, which hide what is going on in it. According to the IDF, the largest lathe found in Gaza since the beginning of the war was found there.

On one side of the hangar there are furnaces for casting mortar bombs and presses for rolling steel plates for long-range missiles. In another corner, IEDs against tanks and people are manufactured, each of which contains tens or even hundreds of kilograms of explosives. These large IEDs supposedly could blow a tank up in the air or punch a huge hole through it when stepped on. In the southeast corner there is a large shaft, missiles several meters long can enter it. An elevator takes them down to the depths of the earth, where the workers will fill them with explosives.

To the right of the hangar where the long-range missiles, mortar bombs and heavy IEDs are made is an innocent block factory. To his left is a clothing store that offers its services to the civilian population, which must frequent the store without knowing of the explosives underground. This repeated practice of dealing with explosives only underground, were designed to survive Air Force attacks while cowering behind Gazan citizens.

There are three or four production centers like this in Gaza and from what I've seen it's hard not to be impressed, especially by the long-range missiles that are about 6 meters long and contain hundreds of kilograms of explosives. We saw these missiles, which are supposed to reach the north, in a separate shed, inside iron sleds in which they are rolled in from one production station to another underground.

"It's a perfect arrangement of 'from the manufacturer to the consumer,'" said David, commander of Sayeret Golani. At the end of the process, a long Hamas original "M-90" is the final product, which should reach a range of about 90 kilometers, approaching the Hadera area and possibly even north of there.

It will take more time

Years ago, Hamas started self-production when Israel cut off its smuggling routes. Until then, missiles and other means of warfare had reached Gaza from Iran and Hezbollah by sea. Smuggled weapons, bought in Libya, were smuggled into the Strip from Sinai through tunnels to Gaza. Hamas slowly learned to develop and produce the missiles it lacked through Iranian guidance, and used dual-use materials such as chemicals and fertilizers, originally intended for agriculture and pipes supposedly intended for irrigation.

The experiments were carried out by Hamas towards the sea or during rounds of conflict that it had with Israel since Operation "Cast Lead" in Hanukkah of 2008. The terrorist organization has gone a long way in the production of the missiles, large rockets and IEDs types and sizes. However, at least Hamas fighters are much less efficient and professional than Hamas' weapons development and production system. As a result, they don't always achieve the full lethal benefit from what their military industry provides them.

9 View gallery

Hamas uses a variety of dual use products to produce weapons

(Photo: IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

The threat is indeed more serious than the security establishment estimated, but we must know that the destruction of this array is an operation in itself, which requires professionals and explosives in unimaginable quantities. The IDF must drive carefully and act at a slow and safe pace. Without its dismantling, the residents of the Gaza Envelope will not be able to return to their homes.

"We will dismantle these Hamas infrastructures," said Golani Brigade Commander, Col. Yair Peli, whose men are still encountering terrorists in the al-Maghazi camp, "but it will take time." When one of the journalists asked him, "How long?", Col. Peli explained. "We have patience. It will take a month, two months, three, as long as it takes. We will be here and do the work so that the residents of the Gaza Envelope can return to their homes, and they will have security and a sense of security."

9 View gallery

IDF shows journalists the extent of Hamas' weapon production

(Photo: IDF Spokesperson's Unit)

The Chief of Staff said on Sunday that the fighting in Gaza will last about a year. When you see the quantities of explosives and the careful work that is required, and the operational accidents that occur during the handling of these enormous quantities, you understand that Lieutenant General Halevi was not exaggerating.