Israelis awoke Monday to what should be a routine annual governmental procedure, but one that they hadn’t seen in 36 months of political instability: The cabinet had approved a draft state budget.

The budget bill, which includes a large number of significant reforms, still has to receive parliamentary approval, but its approval by the government’s ministers is a first and major step forward.

4 View gallery

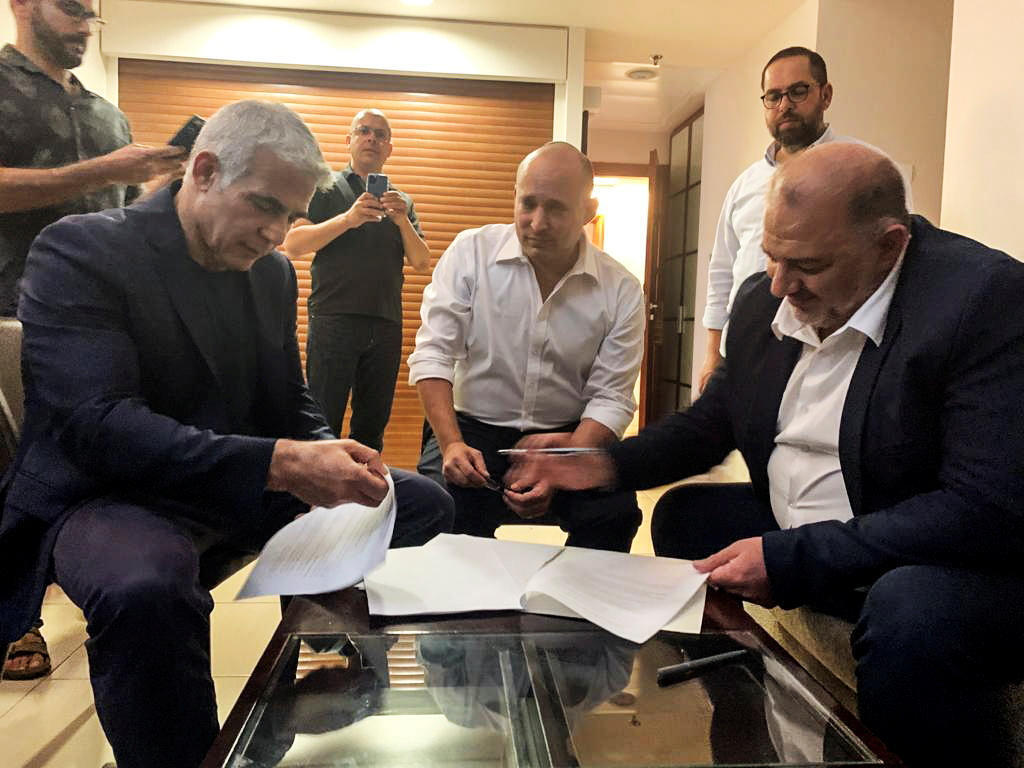

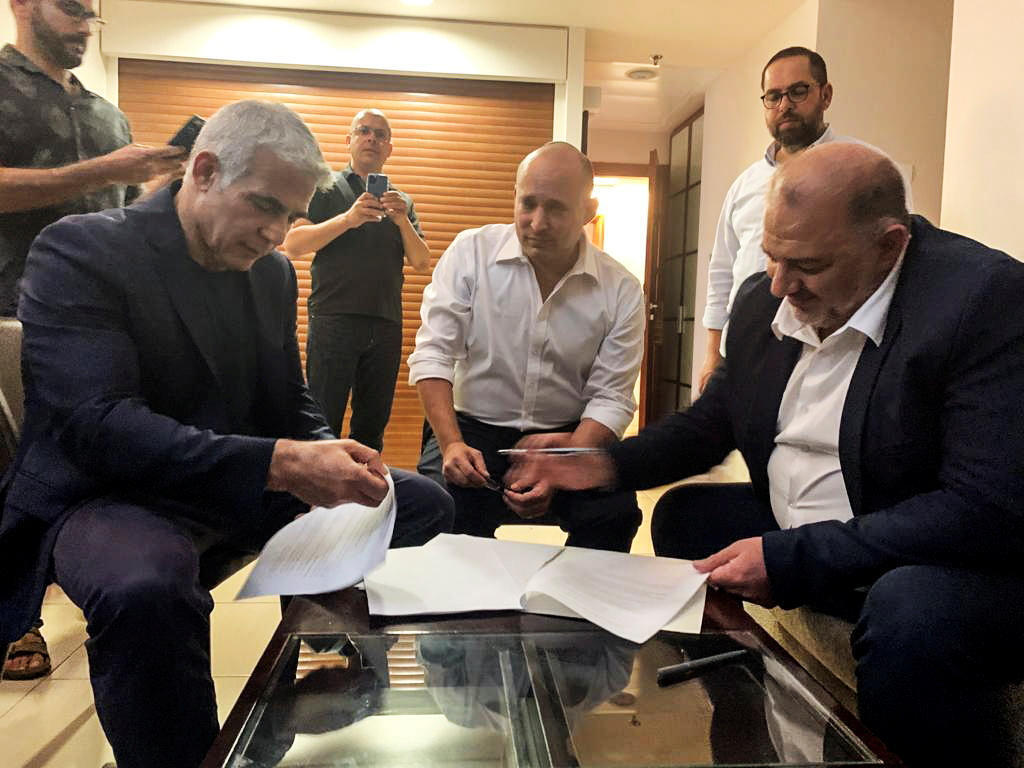

Ra'am leader Mansour Abbas, right, signing the coalition agreement with Yair Lapid, left, and Naftali Bennett that put an Arab party in the coalition for the first time in Israel's history

(Photo: Reuters/Ra'am Handout)

Included in the budget are NIS 29.5 billion ($9.18 billion) intended for Israel’s minorities.

NIS 21.5 billion of that is to be dedicated to a five-year plan for the Arab sector, NIS 3 billion will be directed at the Druze and Circassian minorities, and the Bedouin population will receive NIS 5 billion. The funding allocated to the Arab sector is significantly higher than the NIS 10.7 billion that was approved in the last five-year plan in 2016.

In addition to the funding for five-year plans, it was agreed that NIS 2.5 billion would be directed at fighting crime and violence in the Arab sector. Violent crime has plagued the Arab population in the country in recent years and has cost the lives of many. Arab Israelis have taken to the streets in protest against what demonstrators describe as government and police neglect.

“If [this budget] materializes, it will be a significant leap forward” for the Arab sector, says Dr. Salim Brake, an expert on the Arab society in Israel who teaches political science at the country’s Open University.

“This plan is unprecedented, and if it is realized, it will make a major difference for the Arab population. And at the end of the day, I also think that it will contribute to the state” generally, he says.

The budget bill follows “72 years of neglect” that have created “differences of night and day” between the Jewish majority and Arab minority in the country, Brake says.

The new plans are indeed intended to close the gaps between the majority and the minorities in matters such as education, employment and financial prosperity.

4 View gallery

The Tsofen NGO teaches computer skills to members of Israel's Arab community

(Photo: Courtesy of Tsofen)

A 2019 report by Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics found that in 62 out of 80 “well-being indicators,” Jewish Israelis enjoyed a measurable advantage over their Arab compatriots. The indicators included health, education, personal security and quality of employment parameters.

Brake highlights three major challenges faced by Arabs in Israel.

One issue “is employment,” he says, “opening paths of employment for the Arab population, and especially for Arab women. The level of integration of Arab – especially Muslim and Druze – women into the job market in Israel is one of the lowest in the Middle East.”

Plans at present include a five-year program to increase the presence of Arabs in the tech sector by, among other efforts, encouraging the study of relevant fields.

Only 2.1% of those employed in the high-paying field belong to the sector, according to a 2019 report from the Israel Innovation Authority, which was previously known as the Office of the Chief Scientist, in the Economy Ministry.

The Arab sector comprises 21% of Israeli citizens.

4 View gallery

Israeli Arabs protest in Umm al-Fahm over the state's failure to tackle violence in their community

The second major issue Brake lists is the presence of violence, adding that “violence is also connected to the economy.”

The difficult financial situation, worsened by the pandemic, has pushed people to turn to loan sharks, he says, and this has made its contribution to the rise of violence and crime in Arab Israeli society.

Brake is optimistic that the budget can help to alleviate these first two issues.

However, the biggest problem faced by many Arab Israelis is a shortage of land for building homes, he says. This, though, will not be solved by a bigger budget, but rather demands a change in policy that allocates land for the growth of Arab cities and towns, says the Open University professor.

In contrast to Brake, Prof. Aziz Haidar, a fellow at the Harry S. Truman Research Institute for the Advancement of Peace at the Hebrew University, believes the budget is a drop in the ocean and will be ineffectual in ameliorating the sector’s woes.

“Thirty billion shekels is almost nothing compared to the needs of the Arab population,” Haidar says. “What is needed amounts to hundreds of billions. … This sum will do nothing.”

4 View gallery

Prime Minister Naftali Bennett and Ra'am leader Mansour Abbas in the Knesset as their coalition was sworn in, June 2021

(Photo: AFP)

The professor warns that five-year plans such as those the budget is meant to finance have tended to fizzle out before completion.

“Since they began with these plans − that was in 1961 − there have been 15 five-year plans for the Arab population, none of which ran its course to completion,” he says.

Haidar suggests two steps that he believes will truly help Arab Israeli society.

First, “build industry and trade centers inside or close to Arab towns, something that has rarely been part of the development plans,” he says.

And second, facilitate the founding of Arab tech startups, companies that will grow from within the Arab sector.

These two steps would push for the growth of an Arab economy in Israel, which could ultimately lead to greater integration of Jews and Arabs, but on equal footing, Haidar says.