As Gaza endures its worst humanitarian crisis in decades, former Gazan workers who once relied on jobs in Israel are grappling with devastating loss and a future filled with uncertainty. Entire neighborhoods have been leveled, and much of Gaza’s infrastructure is in ruins as Israel’s intensified military campaign, coupled with an already crippling blockade, has left the Strip’s 2.3 million residents in dire straits.

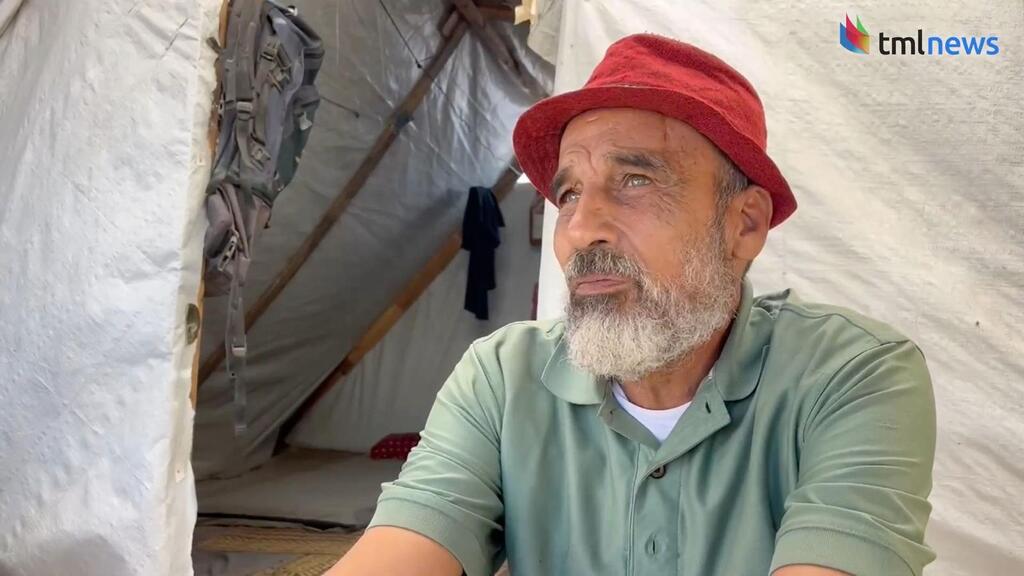

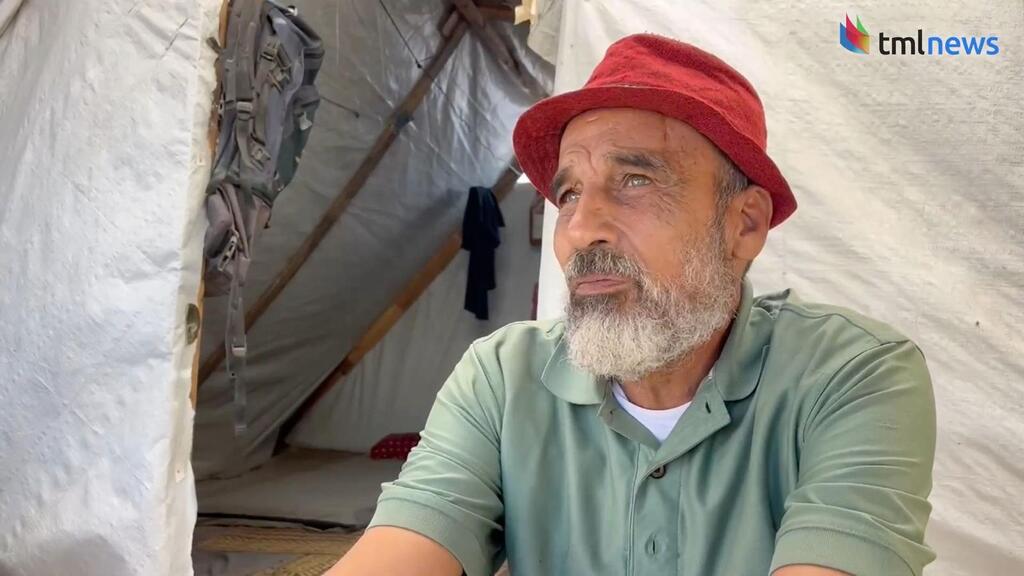

Sami, one of the displaced workers, describes how war has stripped away everything familiar: “It is unbearable. Today, life is impossible. People don’t know how to cope. There is no money, no food. Everyone knows it. When a kilo of onions costs 60 shekels, it’s a catastrophe.”

6 View gallery

Sami, a resident of Gaza and former worker in Israel

(Photo: Screenshot: The Media Line)

He noted that, while in Israel, he worked with both Arab and Jewish Israelis. He said some Jewish colleagues were surprised to work with a Gazan, but it did not prevent mutual interactions.

“When they asked how I got in, I explained that I had a permit,” he told The Media Line. “We are clean people with no connections to Hamas, Islamic Jihad, Fatah, or any other organization. In Gaza, we worked honestly to support our families.”

“This is the result of having bad Islamists in power for years, like Hamas, and it has dragged us back 200 years,” Sami says, expressing frustration with the governing group in Gaza and the toll of ongoing hostilities. “Israel also bears responsibility for our suffering. I have been imprisoned in Israeli jails, and we are caught in a never-ending cycle of violence. Now, we fight for scraps of bread and live in tents.”

The escalating violence has forced tens of thousands to flee their homes, leaving many internally displaced and facing life in makeshift shelters.

Originally from Amman, Sami recalled being caught at the border when hostilities erupted, unable to return home. “The war started while I was at work,” he explaines. “We wanted to leave. We didn’t know what to do because there were no crossings open.”

After being detained by Israeli authorities for a month, Sami returned to Gaza to find that his home had been destroyed and that his wife and daughter were among those killed.

Until recently, cross-border employment provided an economic lifeline for thousands of Gazans, many of whom worked in Israel’s construction and agricultural sectors. In 2021, 7,000 Gazans held Israeli work or trade permits. The following year, the permit quota was increased to 17,000, with a planned increase to 20,000. By 2023, 18,500 Palestinians had visas to enter Israel, but their access was revoked three days after the Hamas attack.

Riyadh, 28, who was born in Turkey, has been living in the southern part of the Strip. He has not seen his father Sami for nine months during the war. He was a medical clown in Gaza and worked in Israel as a painter for 19 days before he got married. Fifteen days later, the war began. His 16-year-old wife was killed during the conflict. Riyadh strongly condemns Hamas for this. “They started the war on October 7. If they had not initiated this, nothing would have happened,” he says.

6 View gallery

Sami, a resident of Gaza, medical clown, and former worker in Israel

(Photo: Screenshot: The Media Line)

For Gazans like Sami, these jobs were essential, providing a steady income in a territory plagued by soaring unemployment and poverty. “I had a permit and was officially employed in Israel,” he recalls, noting he earned approximately 500 shekels a day—a salary that allowed him and his family to live relatively comfortably.

While the majority of workers have either fled Gaza or been killed, The Media Line was able to speak to a businessman who, for security reasons, is not being identified. He has two decades of experience in major industries in Gaza—and is now facing his fourth displacement.

“The period before the war was a symbol of good exchange and cohesion between the two sides. I had great hopes for the future and to continue like this,” he says. “October 7 has destroyed all our dreams and communication on both sides. We blame both Israel and Hamas. They must stop the war immediately.”

When asked why he hadn’t left the Strip, he says that he had “many chances” to do so. He noted that he had been to “the United States, China, and other places” but said he “couldn’t leave” Gaza.

“Even after visiting Ramallah, I couldn’t stay there more than four days and had to return to Gaza,” he says. “We will not leave; this is our land. I want a chance to live like everyone else. My message to the world is that I hope what I am enduring, along with the suffering of my people and children, will never happen again in history.”

Hasan, another longtime worker, shares similar experiences from his 20-year tenure in a block factory in Israel, where he found stability and enough income to support his family in Gaza. “It was generally good, and I earned enough to live a dignified life in Gaza,” he says. “But now, we live like animals. This is the result of having bad Islamists in power, like Hamas. Israel also bears responsibility for our suffering.”

6 View gallery

Hasan, a resident of Gaza and former worker in Israel

(Photo: Screenshot: The Media Line)

Before this latest escalation, Gaza’s labor force had built a fragile but vital relationship with Israeli employers, bridging the gap between the two sides through economic interdependence. For some, this work symbolized a rare opportunity for interaction that transcended the usual hostilities.

While many in Gaza hold Hamas responsible for the conflict, others, like Sami, are outspoken in their criticism of the group’s leadership. “This is not a national movement; it is a betrayal,” he declares.

Hasan echoed these sentiments, saying, “We brought this on ourselves by creating groups like Hamas, who claim to represent Islam but know nothing of it. To me, the Jews are better than the Muslims ruling us here. ... True Islam would never justify their actions.”

- Story reprinted with the permission of The Media Line

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: