Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Fossilized tracks of a dinosaur were found in the garden of a home near the West Bank city of Ramallah, According to Historical Biology Journal.

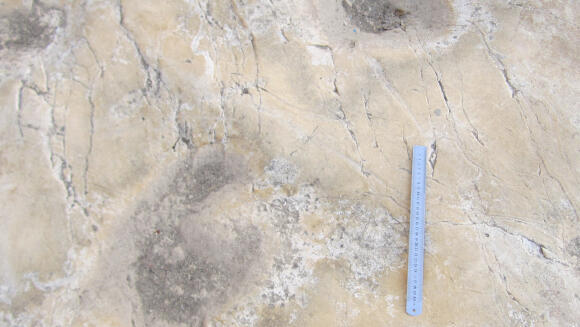

The tracks, which are only the second such found west of the Jordan River, were found in 2019 by a man from the village of al-Bireh and documented by Prof. Abdalla Owais of the Geography and Urban Studies Department at Al-Quds University in East Jerusalem.

Dinosaur tracks were last sighted some 17 kilometers (10.5 miles) away at Beit Zeit near Jerusalem. Both locations are part of the late Early Cretaceous carbonate platform of the eastern Levant. This carbonate platform extends from southern Lebanon to northern Egypt and was part of the southern margin of the Tethys.

The Al-Bireh site was called al-Irsal, named after the neighborhood in which it was found and is dated to over 100 million years ago.

But unlike the tracks observed at Beit Zait - which clearly show a footprint with three frontal fingers, similar to modern-day birds - the al-Irsal tracks were preserved as rounded impressions, making the identification of the animal, or the manner by which they were made, more difficult.

The tracks on the fossils point to an animal trying to remove food from its teeth using the muddy surface.

Similar shapes could be attributed to animal burrows, they could be made by fish searching for food or by the process of erosion in the rock layer.

But the al-Irsal tracks' origin was determined through its appearance on the rock surface, featuring similar patterns at equal intervals like that of a bipedal animal.

Researchers say that the different paths indicate that the two creatures passed by one another, but it is unclear whether they were of the same species.

They also suggest that these prints may have been created by dinosaurs from the Theropoda subspecies, from which birds evolved, or from the chicken-like species Ornithischia. For context, it is speculated that the traces at the Beit Zait belong to an ostrich-like dinosaur from the subspecies Theropoda.

However, it might be too early to draw conclusions about the prehistoric creature who left the footprint.

The preserved tracks in the Judean Mountains indicate that, at least during certain periods at the end of the Cretaceous period, the water over the flooded continental shelf was shallow enough to allow these large animals to walk a long distance from the shore, and potentially even into the sea scavenging for food.