Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

In the early morning at Calcutta's bustling flower market on the banks of the Ganges, pollution obscures the sun and paints the sky a muted gray-brown. Amid the stifling heat of 97 degrees and overwhelming humidity, I find myself engulfed in a teeming sea of people, surrounded by vendors, buyers, porters, rickshaws, trucks, and motorcycles.

Read more:

Struggling to make progress feels futile, like swimming through thick mashed potatoes. Having left my cherished personal space in Israel, I resign myself to surrendering to the relentless human tide of this vibrant city.

It is here, amid the chaos, that I truly grasp what it means to be a tiny drop in a massive tsunami. And oddly enough, it brings a sense of joy. This experience feels timeless, as if this place has always existed and always will, while I am but a transient visitor, soon to fade away.

A few days prior, while seated in the back of Radesh Kumar's rickshaw, my experience in New Delhi evoked a similar sensation. We traveled from the Rohini slum in the city's north, heading towards the center.

The rickshaw's front bumper grazed a sticker urging us to maintain distance from the back bumper of a truck. We found ourselves amid an interminable traffic jam that stretched across the entire horizon. The sun battled to penetrate the smoggy clouds, as the air hung heavy with smoke.

Sirens blared from an array of vehicles, creating a piercing symphony. On either side of the road, the sight of poverty, indifference, and meager existence left a profound impact. And suddenly, out of nowhere, a moment of clarity emerged—a profound understanding of what it truly means to be a part of the human race, a minuscule speck caught within an enigmatic storm.

We all know the only thing truly permanent is change, and yet there has been one constant for as long as we can remember—the undeniable fact that China has held the title of the world's most populous country. However, a significant shift occurred last month when the United Nations announced that India has surpassed China, now claiming the mantle of the most populous nation with nearly 1.43 billion inhabitants.

What once was a narrow gap is set to widen in the coming years as China ages and faces a dwindling birthrate, nearing negative growth. In contrast, India, vibrant and brimming with vitality, will surge ahead. Presently, approximately one out of every five and a half individuals on the planet is Indian.

The repercussions of this shift are poised to impact our world in diverse ways, particularly within India itself, and not solely for the better. The daunting task of nourishing, educating, and ensuring a good quality of life for such a massive population is anything but simple, even for the world's fifth-largest economy (on its way to becoming the third) and a people known for their warmth, wisdom, and resourcefulness.

One needs only glance around to observe the indelible mark Indians have left on various spheres—be it the Vice President of the United States, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, or the CEOs of tech giants like Google, Microsoft, and IBM. They wield influence over Silicon Valley and beyond.

I embarked on a journey to India, aiming to immerse myself in two cities: New Delhi, the nation's capital and one of the world's largest metropolises, boasting a staggering population of over 33 million; and Calcutta, the densely populated city where approximately 15.5 million people reside within a mind-boggling density of over 24,000 individuals per square kilometer (six times more densely-packed than Gaza).

Though separated by a mere 930 miles, these cities stand worlds apart in terms of culture, politics, and economy.

The demographic news has received no official response from both the Indian and Chinese governments, highlighting the failure of each from their respective perspectives. China's birth policy is anticipated to further undermine the nation, while India's absence of a birth policy is expected to come at a significant cost.

The sheer size of India poses challenges, leading to alarmingly high unemployment rates. The official figure hovers around eight percent, but estimates suggest it could be much higher, possibly even double.

The education system is struggling, economic disparities are vast, prompting many to seek better opportunities abroad. The infrastructure in major cities is strained by uncontrollable internal migration, pushing it to the brink of collapse.

At precisely seven in the morning, the aircraft glides gently onto the tarmac of New Delhi's Indira Gandhi Airport. Stepping outside, I am immediately struck by the notable transformation I had been informed about.

The roads have expanded significantly, the city appears much cleaner, particularly along the main thoroughfares, and perhaps most notably, the city center is devoid of the presence of cows. Not a single 'Moo' uttered.

However, the most remarkable change can be witnessed within India's metro system—a colossal mass transit network that has undergone extensive renovation and continues to do so. With ten lines spanning hundreds of kilometers, the system operates at an impressive standard.

The cost of a travel ticket is approximately 50 rupees, about 61 cents. While I do prefer experiencing New Delhi above ground, there is no denying the considerable improvement, especially when punctuality is essential, considering the city's notorious traffic congestion.

After arriving at my hotel in Connaught Place, I swiftly drop off my suitcase and step out onto the bustling street. The scorching heat engulfs me, but I can't help but relish in its familiarity.

It appears that I was missed here too. In this sprawling Metropolis, hardly a soul passes by without stopping me for a conversation and showering me with compliments. "You resemble a movie star!" "Your hair looks fantastic!" Their kind words bring me joy. Everyone is curious, asking about my origins, the cost of my flight, my income, the origin of my shirt, and even my age. I am delighted to engage and provide answers.

The consensus among the locals is overwhelming: the abundance of people in India isn't ideal, pollution and disorder prevail, education is lacking, and life in New Delhi can be challenging and costly. However, there is an undeniable belief that there is nothing quite like India. Here, anything is possible.

I strike up conversations with individuals like Rahul, a 21-year-old living with his rickshaw driver uncle, Ajay, a 23-year-old aspiring to move to California, and Ashok, a 25-year-old curious about my romantic history. The encounters are numerous and diverse. Some may find it bothersome, but I cherish these interactions.

Each person I meet attempts to guide me to various shops, but I am already familiar with their tactics. No, I have no interest in purchasing a carpet, tea, figurines, fabrics, perfumes, or drugs. I decline offers to shine my shoes or clean my ears.

I graciously thank everyone with a smile because I feel content. They all know how to say "Shalom" and "sababa" and have a deep affection for Israel. It is one of the few places in the world, including Israel itself, where Israelis are so widely loved.

In one of the corners, I come across Anil, a 21-year-old. For some reason, I'm immediately drawn to him, even though he asks the same questions as others and tries to lead me to the same shops.

Curiosity piqued, I inquire about his occupation. Anil responds with a casual "nothing," sharing that he is neither employed nor pursuing education. He hails from a neighborhood called Rohini, a name unfamiliar to me.

"Let's grab a chai," I suggest, and we stroll together for about an hour. During our conversation, Anil reveals his aspirations - initially desiring to become a teacher, then shifting his focus to computers after a mere ten minutes, and eventually setting his sights on owning a rickshaw.

I inform him of my upcoming appointments but express interest in meeting again later. He happily agrees, and I hop into a rickshaw to head towards Kahn Market, the vibrant and fashionable district of the city. In New Delhi, one can conveniently book a rickshaw through Uber, sparing the need for constant haggling.

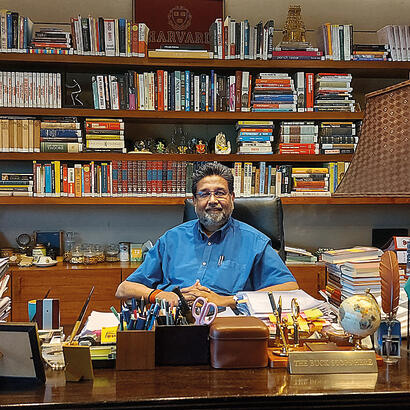

At Cafe Tartal, I encounter Jayanta Ghosal, an experienced political journalist, author, and editor affiliated with the India Today media group. Ghosal displays a keen interest in Israel, having even visited the country as part of a journalists' delegation.

He vividly recalls the informal nature of government spokespersons and the pervasive feeling that he was overdressed wherever he went in Israel. Ghosal expresses admiration for Yuval Noah Harari and was particularly impressed by the Netflix series "Fauda."

According to him, while the Indian government is taking appropriate measures, the issue of population growth remains a significant challenge. Ghosal remarks on India's historical agrarian background, highlighting how British influence transformed the nation for their own benefit, constructing major cities, ports, and railways.

This urbanization process, he argues, has weakened society, likening it to a scenario where all the blood concentrates in the heart, leaving the rest of the body weakened.

Looking ahead? Ghosal is not optimistic. "The order of priorities is distorted," he says. "There are climate, water, deforestation problems - but the government is talking about religious matters. We are moving to the past instead of the future. Towers are being built before the electricity and water grid to support them were laid out."

In a bar, I encounter Anuttama Banerji, a knowledgeable researcher and political analyst based in New Delhi. She holds a master's degree in international relations from both the London School of Economics and Political Science and the University of New Delhi.

Banerji impresses with her proficiency in five languages and displays remarkable intelligence and energy. It turns out she will soon depart India for an internship in London.

According to Banerji, "the nation is changing," but its direction remains uncertain and only time will reveal its course. She finds it quite remarkable that despite the vast population, people in India manage to coexist relatively well.

Together, we contemplate the possibility that polytheism, with its inherent encouragement of openness and tolerance, may play a role in this. Absence of a single ruler allows for diversity. Furthermore, the fact that every Indian is, at minimum, bilingual contributes to the overall harmony. Banerji concludes that the Indian mind possesses flexibility and adaptability.

Banerji also expresses concerns about pressing issues such as unemployment, inadequate infrastructure, and the state of education in India. She emphasizes that these challenges pose a significant danger to the country, asserting that relying solely on academic qualifications just doesn't cut it anymore.

Despite India's status as a democracy with high voter turnout, Banerji observes a concerning shift since the rule of the BJP party, where the dynamics have become centered around Hindus versus Muslims. She cautions that the intensification of this division could lead to unforeseen consequences.

In Banerji's view, religion lies at the heart of many of these issues. She highlights the disproportionate focus on constructing temples while neglecting the construction of hospitals.

According to her, this trend reflects a return to traditional Hinduism and the persistence of the caste system. Banerji expresses apprehension about the potential resurgence of caste divisions, as she sees it as a detrimental development for the country.

Anuttama Banerji shares a profound statement with me that has left a lasting impact: "India is not merely a country; it is a civilization."

I reunite with Anil, who appears without a phone, and together we embark on a rickshaw ride. The rickshaw driver, Rajul, expresses his grievances about overcrowding, pollution and the government.

He mentions the hardships of providing food and financial stability for his two children. According to Rajul, things were better in the past, but not anymore. Our journey takes us to the Muslim neighborhoods in Old Delhi, specifically the market situated beneath the magnificent Mosque.

The area is teeming with people, and the density is overwhelming. It becomes apparent that the Muslim neighborhoods in New Delhi, much like those in Calcutta, are significantly neglected compared to other parts of the city, with striking disparities in living conditions. The deteriorating infrastructure further underscores the challenges faced by these communities.

We sit down for a cup of chai in a small stall that serves multiple purposes: it's a clothing store, a tailor's shop, a chicken slaughterhouse, and even a garage. The owner of the establishment introduces himself as Muhammad Ali (no, not the one you're thinking of...), a 46-year-old man who appears much older due to the hardships he has faced in life.

It's a common sight in India, where the struggles of the poor often age them prematurely. Ali, a lifelong resident of New Delhi, proudly shares his lineage: "I was born here, as was my father, and my child as well." He has a single child who works as a rickshaw driver, while his wife has sadly passed away.

Business is tough for Ali, but he remains hopeful that things might improve. While he takes pride in his country, his opinion of Prime Minister Modi is less favorable. With a gesture, Ali draws a line across his throat, symbolizing slaughter.

"He's a liar," Ali asserts, "a bad man." Others present at the multifunctional establishment, whether they are customers or workers, tend to agree with Ali's sentiment. As Muslims, they perceive Prime Minister Modi as a genuine threat to their lives and well-being.

We make our way through the vast and worn-out Muslim market that stretches in front of New Delhi's magnificent Red Fort. Despite the shabbiness of the surroundings, the people here exude happiness and wear smiles that never fail to leave an impression. As an outsider, I was accustomed to associating poverty with misery, but in India, there are intangible qualities that our eyes cannot perceive.

Leaving the market behind, we head towards the "Kashmiri Gate" metro station and board the train, destined for the Laritala neighborhood, the final stop on the red line. The metro is bustling with activity, and security measures are stringent.

Dedicated carriages for women and designated spaces within each carriage ensure safety and comfort for female passengers. As we move away from Kashmiri Gate, the neighborhoods we pass through grow increasingly impoverished.

A metro ticket, as previously mentioned, costs 61 cents and is in the form of a plastic coin. I ask Anil what he would have done if we hadn't crossed paths today. With a smile, he replies, "Nothing much, just wandering around." In response, I invite him to meet me at my hotel tomorrow at 11, suggesting that we spend some leisurely time together, exploring the city.

The following morning, I rendezvous with Anil, and together we embark on a journey to Rohini, a slum situated in the northwest corner of the city. We hop into Radesh's rickshaw and begin our expedition.

The duration of the trip exceeds an hour, during which I experience a surge of fear on numerous occasions—moments that make me feel as if I've faced death almost a hundred times, excluding the 30 instances that felt painfully real.

As we depart from the bustling city center, the absence of cows becomes apparent. Exhausted, they lie scattered on the traffic islands along the road. Progressing further away from the heart of the city, the landscape undergoes a transformation.

The sight of elegant houses gradually gives way to less appealing structures, transitioning into dilapidated residences, makeshift dwellings constructed from tin, and ultimately, flimsy nylon shacks.

Along our route to Rohini, we pass through neighborhoods more deprived than one could fathom. I request Radesh to slow down as I yearn to witness the reality before me.

At one of the intersections, we encounter a policeman who decides to target us, sensing an opportunity for exploitation. In the face of his threats to revoke Radesh's license, I reluctantly offer a bribe of 1,000 rupees to secure our passage and prevent any further repercussions.

Upon reaching Rohini, we ascend a decrepit staircase that leads to the one-room apartment where Anil's family resides—coincidentally, they share the same first name. Within the confines of this minuscule space, eight individuals call it home, and while it may be cramped, it is meticulously kept clean.

The monthly rent amounts to 3,000 rupees, roughly equivalent to $36, and an additional $11 is allocated for electricity. Occasionally, the weary ceiling fan halts its rotation, allowing an overwhelming heat to permeate the room.

The head of the household has unfortunately passed away, leaving Anil's mother to sustain the family by collecting alms at the train station. Curious about her earnings, I inquire about the amount she typically accumulates.

Anil reveals that earning 100 rupees, equivalent to five shekels, is considered a good day. Within the confinements of the room, Anil recounts tales of violence and brutality stemming from drug-related disputes.

Payeh, Anil's sister-in-law, bears the visible scars of such encounters, with one eye tragically missing. It was lost during a fight that transpired approximately two months ago. Intrigued, I inquire about the cause of the altercation, to which Anil responds that it was over a sum of 150 rupees, less than $2. Payeh is merely 22 years old, and yet has already endured such hardship.

The children residing in the household are deprived of education as they are unable to afford the expenses associated with schooling, despite it being offered free of charge. The costs of books and uniforms prove to be too burdensome.

I inquire about the price of a shirt, and Anil informs me that it amounts to around $8. Moved by their circumstances, I decided to contribute by providing funds to the elderly lady overseeing the room.

I offer her money for three shirts, settle the bill at the grocery store, and leave them with the remaining cash I possess, except for the amount required for my return journey, along with an additional sum for any unforeseen bribes.

I attempt to lighten the atmosphere with a feeble laugh, remarking that it's unfortunate they don't offer credit. However, the reality of the situation dampens any semblance of humor. Anil shares his sentiments with me, expressing, "Externally, I may appear happy, but internally, I'm filled with sadness. That's just how it is. That's life. This is India."

Later that day, I stroll through enchanting gardens adorned with lush trees and graceful fountains. The tourist guides suggest, "If you find yourself in the city, make sure to visit the center, where you can indulge in the melodies of classical music or engage in pleasant conversations over a cup of tea, all while overlooking the serene lily pond... The center transports you to a different time and dimension."

I encounter a prominent journalist from a renowned media establishment in that very place. I share with him that I had just come from Rohini, to which he responds with a look of astonishment.

He confesses that although he was born in New Delhi, he has never visited that part of the city. In the cafeteria, affluent Indians subject the waitstaff to mistreatment. The cost of my sandwich and a glass of juice surpasses what Anil's mother manages to accumulate in a month and a half of enduring humiliation.

The journalist proceeds to order ice cream. I am acutely aware that such disparities exist, yet it pains me, as something within me feels torn apart by the glaring divide.

The sandwiches leave a bland and unappetizing taste in my mouth, and the juice even makes me feel queasy.

The journalist, who prefers to remain anonymous (as is often the case with many journalists—India may boast of being a robust democracy, but one can already sense the erosion taking place), shares insights about how India "came to embrace globalization more than a decade after China, but now finds itself lagging behind, facing significant challenges in catching up."

He discusses how "the previous government's corruption tarnished the economy and deterred potential investors," as well as the pressing issues surrounding infrastructure and more.

The journalist emphasizes that the key to India's success lies in opening up additional maritime trade routes and forging more international agreements. Concluding his thoughts along with the last spoonful of ice cream, he asserts that what India truly needs is a globally recognized indigenous technological advancement.

The following day, driven by a sudden surge of curiosity, I go to Calcutta, the capital of West Bengal. Despite never having set foot there before, I find myself enamored the moment I arrive. It's eight o'clock in the evening, and I'm greeted by the scorching heat of 38 degrees Celsius, accompanied by an unfamiliar level of humidity. Calcutta and I experience love at first sight.

This city, somewhat weathered and worn, has long surpassed its glory days as the capital of the British Empire in India. It now bears the marks of aging, with pockets of poverty but not destitution, frayed edges, and a somewhat hollow center, all while striving to maintain its cultural allure. It's as if Calcutta reflects a reflection of myself. I glance in the mirror and find shades of Calcutta staring back at me.

There's an eccentric, vintage tropical charm to this place, with its aging yellow taxis that appear charming from the outside, yet leave you bewildered once you step inside, pondering how and why these vehicles continue to persevere, driven solely by the determination of their drivers.

As mentioned, Calcutta boasts the highest population density in India, six times that of Gaza. It's impossible to truly convey the essence of Calcutta to those who have never experienced it firsthand. Even while being present in this city, I find it challenging to believe that it exists in reality.

After settling my belongings at the hotel, I venture out to explore the city. Within just half an hour in Calcutta, I come across more books and bookstores than I encountered during my four-day stay in New Delhi.

Calcutta proudly holds the title of being the cultural and artistic capital of India. While it undeniably stands as one of the most densely populated cities in the world, it somehow manages to exude an inexplicable sense of safety.

If New Delhi tops the crime charts among major Indian cities, Calcutta takes a decisive stand against it. While the Indian capital might woo you with excessive enthusiasm, Calcutta plays hard to get. Nobody pays much attention to you here.

If 70% of my energy in New Delhi was consumed by conversations with passers-by, in Calcutta, I'm like air (if only there was enough air). Even the beggars show little interest in me—take it or leave it, their choice. This city is filled with self-assured individuals, leaving me with ample time to simply observe and absorb its essence.

Upon initial observation, Calcutta appears to be much grittier and tougher compared to New Delhi. However, after spending a day or two in this city, one begins to perceive a certain softness hidden beneath its rough, weathered, and prickly exterior.

Poverty here is front and center, but the wealth disparity is not as pronounced as in New Delhi, creating a less stark contrast. It becomes evident that Calcutta is a city predominantly inhabited by the lower castes.

Calcutta boasts a somewhat secular existence, where restaurants serve meat, including beef, and alcoholic beverages. The populace possesses darker skin tones, and there is a higher representation of women on the streets and in places of entertainment.

Temples, on the other hand, are noticeably fewer in number, and even those that do exist worship different deities compared to New Delhi, with special reverence given to goddesses such as Durga and Kali.

Kali, the fierce and wrathful goddess of infinite energy, time, and change, holds a prominent position as the city's patron deity (perhaps explaining the city's name, which is derived from hers). She embodies darkness, much like the city's inhabitants. Despite the bustling and cacophonous nature of the entire city, one can sense a certain tranquility among its residents, albeit in their peculiar and contrasting manner.

There is an underlying tension between the realization that life holds little value and the simultaneous celebration of every fleeting moment. Calcutta stands as a city that inherently defies all earthly and heavenly rulers.

In contrast to the sense of Indian patriotism prevalent in New Delhi, Calcutta struck me with its distinct display of Bengali patriotism. Both culturally and geographically, the people of Calcutta share a closer affinity with neighboring Bangladesh than with far-off New Delhi. It was in Calcutta that I witnessed something unimaginable in New Delhi—a pride flag proudly waving in the cityscape.

In the Muslim enclave of Calcutta, I come across yet another notable contrast between New Delhi and this city.

While the former displays a pro-Israel sentiment, with widespread admiration for Israel and popular TV shows like "Fauda" on Netflix, the larger Muslim population of Calcutta, comprising around 30 percent of the city, fosters a predominantly pro-Palestinian sentiment.

Contemplating this disparity, I make a personal decision that if anyone asks about my origin, I'll simply claim to be from Italy. I even practice a few Italian phrases, but soon realize that my location has rendered such details inconsequential. It becomes clear that no one really cares whether I hail from Italy or Mars, for that matter.

During midday, I have an appointment with one of the wealthiest individuals in Calcutta, Harshavardhan Neotia. At 61 years old, he serves as the head of the Ambuja Neotia Group, a conglomerate involved in real estate, infrastructure, hotels, healthcare, investments, and he also holds the position of Honorary Consul of Israel in India.

Mr. Neotia proves to be a genuinely pleasant person as he graciously welcomes me into his opulent office. The entire complex, situated in the northern part of the city, represents a facet of "New Calcutta."

Our discussion revolves around Indian democracy and the pressing need for improved infrastructure. Although Mr. Neotia keeps a distance from politics as a businessman, it becomes evident that he believes the government is moving in the right direction for India's benefit.

We indulge in a delectable lunch served in his private dining room, where the flavors of Indian cuisine truly captivate my palate. Amid our meal, four individuals continuously tinker with the air conditioner, causing some disturbance around us.

Once again, I am confronted with a somber realization: while wealth may appear illusory, poverty remains an undeniable reality.

The following day, I have a meeting with Yael Silliman, a member of Calcutta's minuscule and conflicted Jewish community. Their story carries both a sense of sadness and elements of comedy.

Presently, fewer than 30 Jews remain in Calcutta, a stark decline from what was once a thriving and vibrant community. Most of the remaining members are in their eighties, and unfortunately, they find themselves embroiled in disagreements and bitter disputes over financial matters. Within the city, the community possesses three synagogues, schools, an ancient cemetery, and a considerable amount of real estate.

Yael Silliman graciously hosts me in her home. She dedicates her research and writing to the fields of anthropology and population studies in India, approaching these topics from a feminist and leftist perspective.

She holds strong opposition to Prime Minister Modi, equating him to (Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin) Netanyahu, as she feels deeply connected and passionate about both the events transpiring in India and Israel.

A Calcutta native, she spent several decades in the United States before returning to her childhood home approximately ten years ago. Presently, she resides with her elderly mother and a small team of household staff.

Yael Silliman introduces me to the fascinating term "Jugaar," which encapsulates the essence of the Indian spirit. This slang word represents a unique blend of resourcefulness, ingenuity, and adaptability.

According to Yael, the greatest challenge lies in the shortcomings of the education system. Indian education predominantly revolves around pursuing degrees, which stifles the Jugaar mentality.

The focus is on attaining white-collar jobs, resulting in the gradual disappearance of traditional skills such as carpentry, weaving, and various other artistic pursuits that are deeply rooted in Indian culture.

She laments that many individuals forsake these traditional crafts in pursuit of prestige and monetary gains, not all of which they merit. She emphasizes that India has not only endured exploitation under British rule but is now experiencing self-inflicted harm due to its own actions.

In the bustling heart of the city, at Presidency University on College Street, I have the opportunity to meet Professor Navras Jaat Aafreedi. Having completed his postdoctoral research at Tel Aviv University and Cambridge, he holds the distinction of teaching the only academic course in Southeast Asia on Jewish-Muslim relations, anti-Semitism, and the Holocaust.

Reflecting on his childhood, Professor Aafreedi recalls being captivated by the notion that Jews were often scapegoated and blamed for various societal issues. This intrigue sparked his academic journey and propelled him to delve deeper into understanding the dynamics surrounding Jewish history and their relationships with other communities.

Professor Aafreedi expresses concern about the escalating tensions and discrimination faced by Muslims in India. He draws attention to the ominous signs that, if left unaddressed, could lead to a humanitarian crisis comparable to the Holocaust.

While the Holocaust serves as a global reminder of the dangers of unchecked hatred, Professor Aafreedi believes that in India, it has unfortunately become a disturbing model.

He highlights the increasing legislative measures targeting Muslims under the guise of revoking social benefits, the rise of inflammatory content on platforms like YouTube inciting violence against Muslims, the process of ghettoization, and the alarming normalization of rape as a patriotic act, particularly in the northern regions of the country.

These concerning developments indicate the need for urgent attention to prevent a potential tragedy.

In reference to Mother Teresa, the esteemed saint of Calcutta and a fellow Nobel laureate hailing from the city, she once said, "You can find Calcutta anywhere in the world, if only you have eyes to see."

Far be it from me to disagree with the great one, for whom a Nobel prize is the least of her accomplishments, but my doubts about her sentiment linger. There is an unmistakable uniqueness to this city, and it is uncertain whether the world could accommodate another place quite like it.