Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

In the Jaljulia area near Qesem Cave, close to Rosh HaAyin, unique 400,000-year-old stone tools were discovered, used for hunting and processing fallow deer.

The finding was published in the journal Archaeologies, led by Vlad Litov and Prof. Ran Barkai from the Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures at Tel Aviv University.

For about a million years, early humans used stone tools called scrapers to process hides and scrape meat off the bones of large game they hunted. In Israel, hunters primarily targeted elephants, which provided most of their calories. However, the study reveals that in the late Lower Paleolithic period, around 400,000 years ago, after elephants disappeared from the region, Israeli hunters shifted their focus to fallow deer, which were much smaller and swifter.

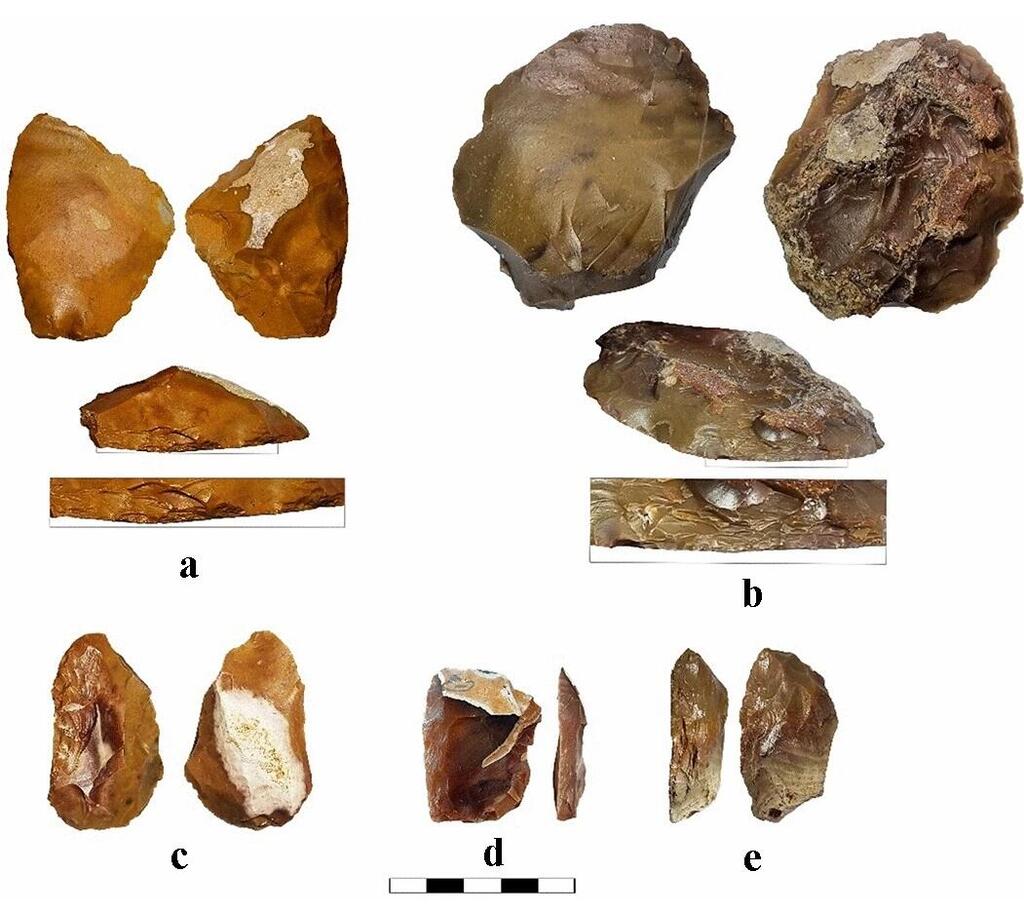

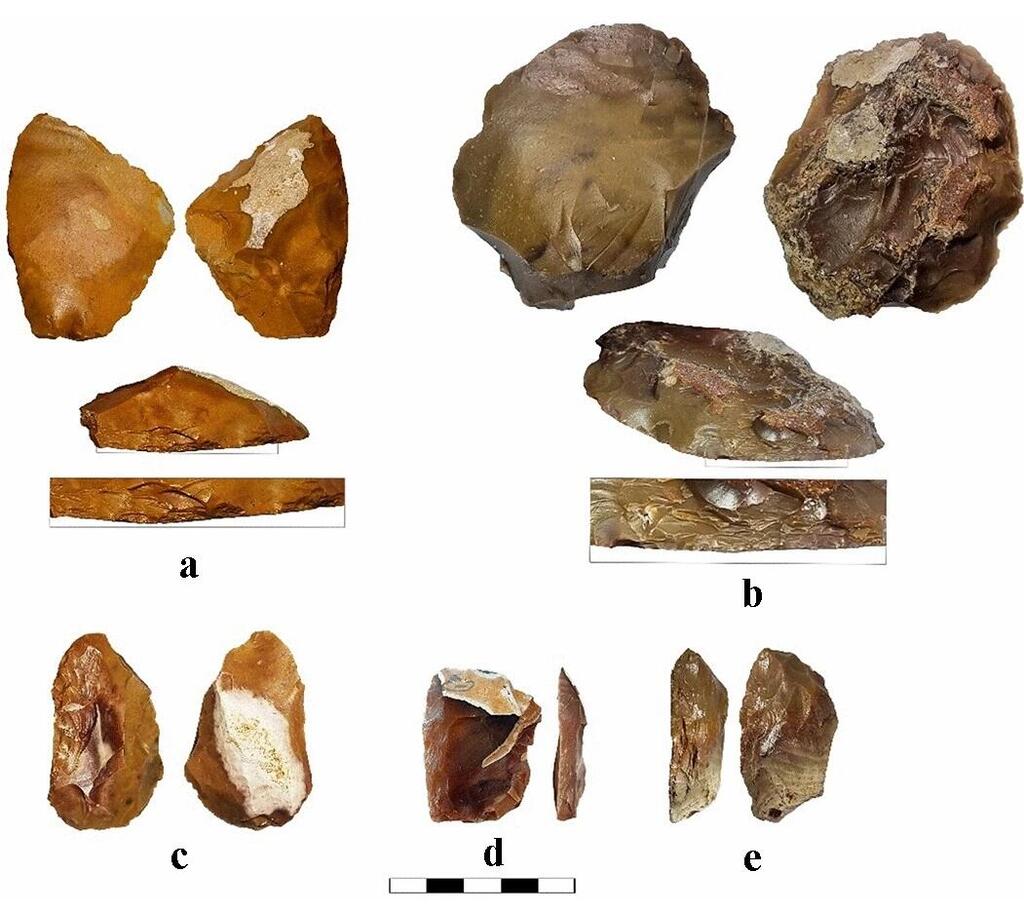

These stone tools were characterized by an active edge shaped like scales, allowing them to be used for both cutting and processing hides. The researchers believe that with the disappearance of elephants, early hunters had to adapt their technology to hunt, butcher, and process the agile fallow deer that lived in the region at that time.

Additionally, the unique stone tools were made from flint sourced from the Samarian hills, east of Jaljulia and Qesem Cave, which were also the calving grounds for fallow deer. Researchers suggest that Mount Ebal and Mount Gerizim were considered sacred to ancient hunters as early as the Paleolithic period.

3 View gallery

Examples of scrapers shaped by Quina-like retouch from the Late Acheulian Jaljulia

(Photo: Tel Aviv University)

Litov explained: "In this study, we sought to understand why stone tools changed throughout human prehistory, focusing on the technological shift in scrapers during the Lower Paleolithic period, around 400,000 years ago. We discovered that during this time, there was a dramatic change in the human diet, likely due to the composition of the fauna: large animals, particularly elephants, disappeared, and humans had to hunt smaller animals, mainly fallow deer."

He added, "Hunting a large, cumbersome elephant is one thing; hunting a swift fallow deer is a completely different story. Butchering a fallow deer is also a more complex and delicate task. This is why we see the emergence of new scrapers with more refined, sharp, and uniform active edges compared to the simple scrapers used by the Acheulean culture for a million years to butcher elephants and other large animals."

Archaeologists from Tel Aviv University excavated the Jaljulia archaeological site near Highway 6, where Homo erectus likely lived, and relied on findings from the nearby Qesem Cave archaeological site. At both sites, many advanced scrapers made from flint not found locally—its closest sources being in the Ben Shemen Forest to the south and the western slopes of Samaria to the east—were discovered.

Prof. Barkai added: "In our research, we identify links between technological developments and changes in the animals that early humans hunted and consumed. For years, scientific research believed that changes in stone tools resulted from the biological and intellectual evolution of humans. We show that the connection is both practical and perceptual: On one hand, humans began making more sophisticated tools because they had to hunt and butcher smaller, swifter, and leaner animals."

He further noted, "On the other hand, we also identify a perceptual connection: The calving areas of fallow deer are in the Ebal and Gerizim mountains of Samaria, and the scrapers from Jaljulia and Qesem Cave used to butcher fallow deer were made from flint from the Samarian hills—a significant distance of about 20 kilometers from Jaljulia. In other words, we found a link between the source of the fallow deer and the flint used to butcher them. We believe this connection had perceptual significance for these hunters. They knew where the fallow deer came from and it was important for them to use tools made from this specific flint to butcher them. This phenomenon is known worldwide and remains prevalent among indigenous groups today."

Prof. Ran BarkaiPhoto: Tel Aviv University

Prof. Ran BarkaiPhoto: Tel Aviv UniversityLitov concluded, "We speculate that the Samarian hills were considered sacred by these ancient people because they were the source of the fallow deer. It's important to note that in Jaljulia, we find many other tools made from stones with different origins. When the local inhabitants saw the elephants disappearing, they became reliant on fallow deer. They identified the source of the abundance of fallow deer and began developing unique scrapers there. This is the beginning of a phenomenon that later spread throughout the world.

"These scrapers first appear in Jaljulia, between 500,000 and 300,000 years ago, still on a small scale. Shortly thereafter, from 400,000 to 200,000 years ago, they appear on a much larger scale in Qesem Cave. Additionally, on Mount Ebal, where an altar attributed to Joshua bin Nun is located, and where the 'Covenant of the Pieces' may have been performed, many butchered fallow deer bones were found. It seems that fallow deer and the Samarian hills were sacred to the people of Israel as well, hundreds of thousands of years after the events described here."