What separates religion from magic? How is the Jewish world connected to magic and why did certain prayers become associated with protective rituals? A new exhibition at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem attempts to answer these thorny questions.

Titled “Hear, O Israel: The Magic of the Shema,” the show hones in on the Shema, an important Jewish prayer that has been recited for millennia. The first verse of the Shema – “Hear, O Israel: the Lord is our God, the Lord is one” – comes from Deuteronomy and expresses the centrality of monotheism to the Jewish faith.

3 View gallery

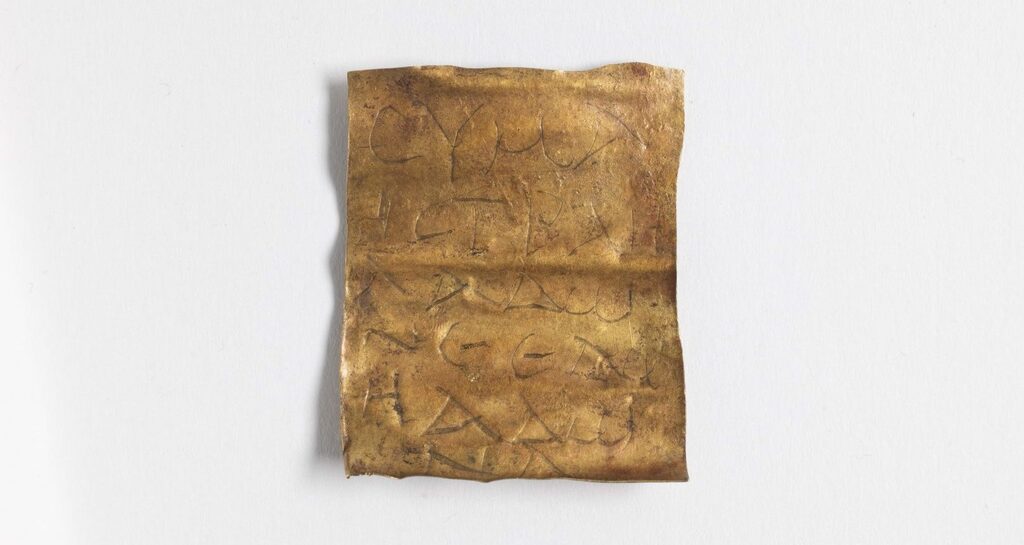

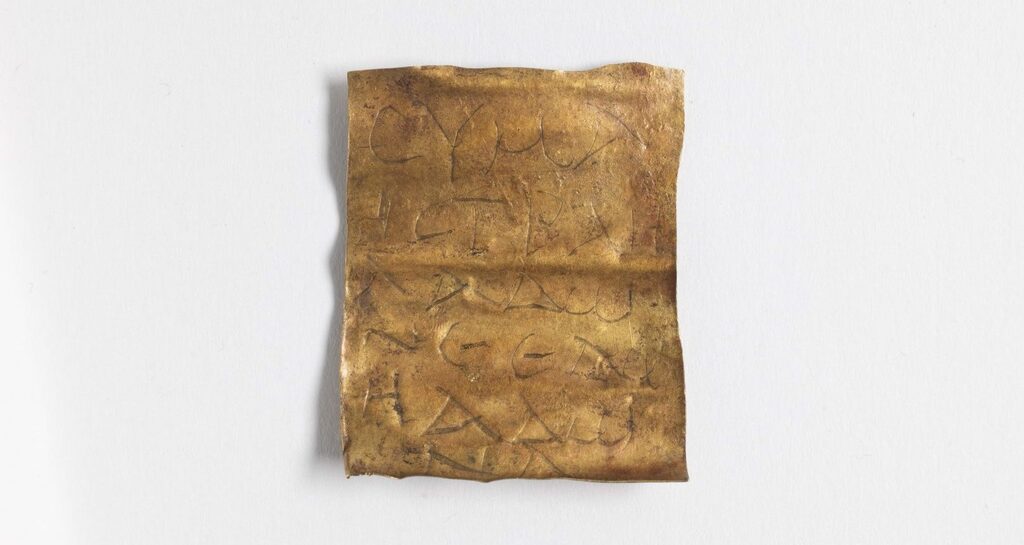

Gold amulet with the Shema written in Greek letters, third century, Halbturn Austria

(Photo: Israel Museum)

Observant Jews recite it several times a day, including before going to sleep. Due to a biblical commandment, the verses of the Shema are also affixed to the doorposts of Jewish households in the form of a mezuzah, as well as included within tefillin (or phylacteries), which are worn during some prayers.

But as the exhibition at the Israel Museum demonstrates, the prayer was also incorporated into Jewish amulets since ancient times. At the show’s entrance lies a small yet curious-looking piece of gold plate in a glass display case. Dating back to the third century CE from Austria, the first verse of Shema is written on it in Greek letters that are barely visible to the naked eye.

According to Nancy Benovitz, one of the exhibit’s curators and a senior editor in the museum’s archaeology department, this gold plate is the earliest known instance of the Shema being used in a Jewish amulet.

“It was rolled up and put in a little case,” Benovitz said, adding that the amulet was found buried alongside a young child.

Next to this intriguing object is a silver armband, inscribed with the first two paragraphs of the Shema prayer and Psalm 91:1 in Greek. This sixth-to-seventh-century piece is originally believed to be from either modern-day Israel or Egypt.

It was this armband-amulet that catalyzed Benovitz to seek out other surprising examples of the Shema being used for protective magic. “It says in the Bible that you can’t go to sorcerers and shouldn’t allow sorcerers to live, but we’re not exactly talking about sorcery,” she related. “We’re talking about beneficial practices.”

3 View gallery

Amulet-armband inscribed with the first two paragraphs of the Shema prayer and Psalm 91:1 in Greek

(Photo: Israel Museum)

The amulets, charms, and spells at the Israel Museum were intended to protect their bearers from ill health or misfortune, while others aimed to impart households with protection.

A fascinating series of rare magic pottery bowls from fifth- to seventh-century Iraq reflect a curious magical practice that was once used by both Jews and non-Jews alike in Babylonia. At the center of the bowls are drawings of strange figures – demons, apparently – surrounded by quotes from the Bible that were written in order to trap them inside.

“They’re actually magic traps for demons,” explained Dudi Mevorah, curator of Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine archaeology at the Israel Museum. “It’s a specific thing that exists only in Babylonia between the fifth and seventh centuries CE, mostly written in Aramaic,” he said.

The bowls were fairly inexpensive to procure and were buried beneath the floor of a household or shop for good luck. “You write the spell within the bowl, you sometimes draw the demon at the center of the bowl – so that he’s trapped both by the bowl and by the spell itself,” Mevorah said.

The museum exhibition provides many other such examples of magical rituals, including manuscripts on kabbalistic practices. It culminates with a row of displays that focus on how the Shema was used in ritual objects prescribed by Jewish law, such as tefillin (phylacteries) and mezuzot. Both are essentially cases that contain scrolls with the words of the Shema.

3 View gallery

Magic bowls from present-day Iraq, which date back to the fifth- to seventh-century Iraq CE

(Photo: Israel Museum)

The juxtaposition of these ritual objects with the other magical items nearby is intended to raise questions about the relationship between religion and magic. Can tefillin and mezuzot also be viewed as amulets?

“If you look back at the Jewish tradition you [can] see that there’s magic even in Bible,” Benovitz affirmed. “It’s just that the word magic that throws people off but really, it’s very much part of our culture. There’s magic in the Talmud, in rabbinic texts, and all sorts of Jewish contexts.

“What’s the difference between religion and magic? Can you really draw a line between them?” she asked. “The answer is: It’s very hard and scholars have been trying for hundreds of years to define the two.”

The article was written by Maya Margit and reprinted with permission from The Media Line