Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

Excavating a Late Bronze Age tomb in northern Israel's Tel Meggido, scientists discovered a skull with a square hole that is believed to be a rare Near East testimony to ancient brain surgery, according to a new study published Wednesday in the journal PLOS ONE.

The procedure, called trephination, is one of the oldest surgical procedures known to mankind and involves drilling a piece of bone and excising it, most commonly from the skull.

3 View gallery

Remains of siblings unearthed in Tel Meggido

(Photo: Kalisher et al., PLoS One, 2023)

The findings from the 2016 excavation at the historical site indicate that the procedure was performed as early as 3,500 years ago.

Rachel Kalisher, a Ph.D. candidate at Brown University’s Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World, led the expedition. Researchers discovered the remains of two upper-class brothers who resided in Megiddo, then a bustling urban center, around the 15th century BCE.

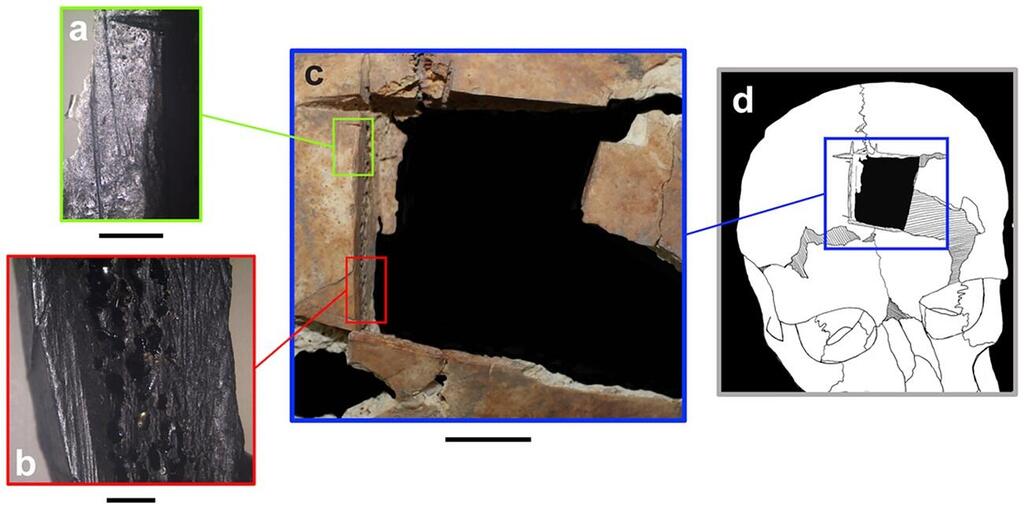

Kalisher and her team found that one of the brothers underwent angular notched trephination before he died, a procedure that involves cutting the scalp, using a sharp-edged instrument to carve four intersecting lines in the skull. She believes it's the earliest evidence of this kind of procedure found in the ancient Near East.

“We have evidence that trephination has been this universal, widespread type of surgery for thousands of years,” Kalisher said. “But in the Near East, we don’t see it so often — there are only about a dozen examples of trephination in this entire region. My hope is that adding more examples to the scholarly record will deepen our field’s understanding of medical care and cultural dynamics in ancient cities in this area.”

Prof. Israel Finkelstein, head of the School of Archaeology and Maritime Cultures at the University of Haifa, says that 4,000 years ago, Megiddo controlled Via Maris, an ancient trade route linking Egypt to Syria and Mesopotamia, making it one of the most prosperous cities of its time.

Kalisher says that since the remains of the two brothers were found next to a palace, as well as the fact that they were buried alongside clay tools made in Cyprus as well as other valuables, it is believed they belonged to the upper echelon of society.

One of the brothers had an awkwardly angled jaw, believed to be some sort of oral dysplasia which perhaps necessitated the procedure in the first place.

The siblings' unusual bone structure is believed to be a sign of anemia or nutritional deficiency in childhood. This could also explain why both died relatively early in their life, the younger brother dying between his late teens and early 20s and his older brother somewhere between his 20s and 40s.

Kalisher believes the cause of the brothers' death was some sort of infectious disease as their skulls were marked by lesions consistent with an infectious disease like tuberculosis or leprosy.

Kalisher says that if the procedure was designed to keep one of the brothers alive, it failed since he apparently died shortly thereafter.

However, many questions remain unanswered, such as why some skulls that showed signs of trephination had round holes while others had more angular notches. It's also unclear how common was the procedure and whether it was performed by other contemporary civilizations.

"Your health needs to be severely compromised for that procedure to even be necessary," Kalisher said. "I'm intrigued as to how widespread it was and would like to cross-reference other examples to come up with a better picture. The evidence also shows that despite some misconceptions, empathy and solidarity were actually quite common in those days, even dating back to the time of Neanderthals."