Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

A new study provides compelling evidence for the early presence of the Ethiopian wolf in the African continent, as far back as 1.5 million years ago.

More Stories:

The study, which was held by staff of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, contradicts previous claims suggesting the wolf arrived in Africa only about 20,000 years ago from Eurasia, and was published in the journal Communications Biology.

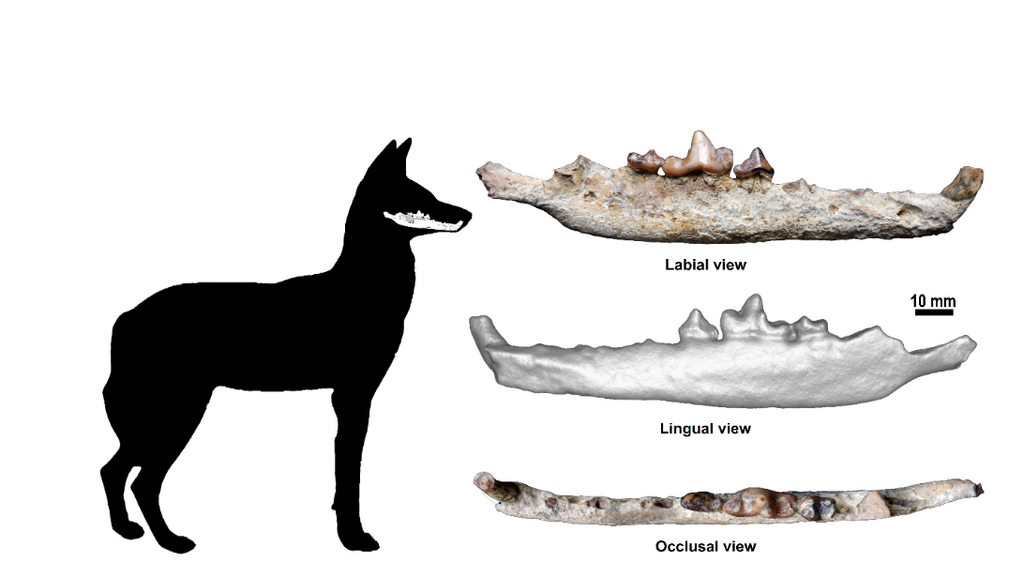

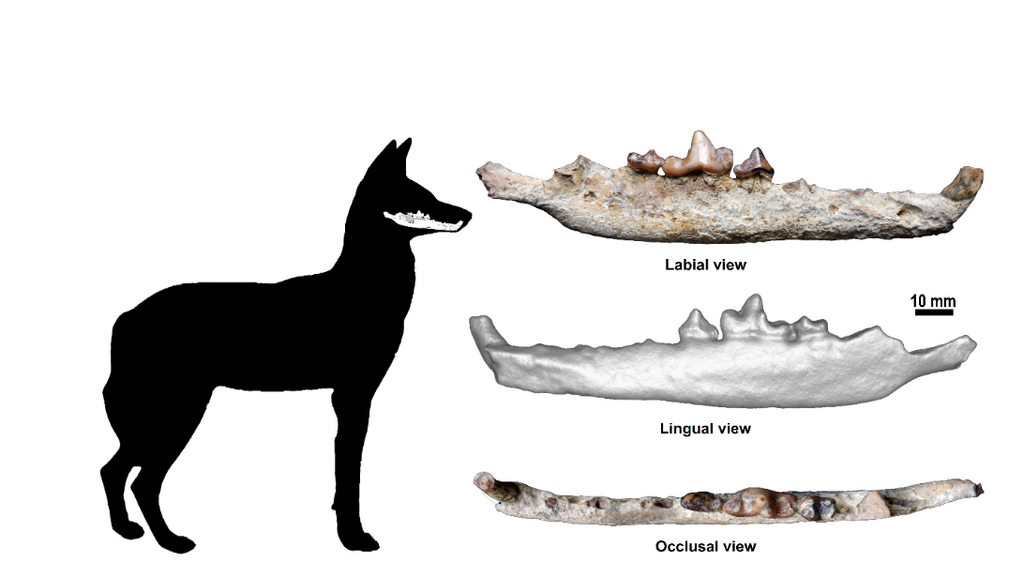

During excavations carried out in 2017 at the Melka Wakena archaeological site located in Ethiopia, led by Prof. Erella Hovers and Dr. Tegenu Gossa from the Hebrew University's Institute of Archaeology, a mandible belonging to the canid family was discovered, which is estimated to be around 1.5 million years old.

The mandible was identified by a team of researchers from the University of California, Berkeley, led by Prof. Bienvenido Martínez-Navarro from the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution (IPHES) in Tarragona, Spain, as the first-ever fossil of the Ethiopian wolf.

The Ethiopian wolf (Canis simensis) is an endangered species facing extinction. It is of medium size, weighing between 12 to 18 kilograms, and is found exclusively in Ethiopia. Its limited ecological and unique adaptability allows it to survive only in areas above 3,000 meters above sea level, where the climate is relatively cool for a significant part of the year.

4 View gallery

Mandible found by researchers

(Photo: Tegenu Gossa, Bienvenido Martínez-Navarro C. J. Sharp; distributed under CC BY-SA 4.0)

Currently, there are only around 500 individuals of the Ethiopian wolf remaining, dispersed in isolated populations primarily in the Bale and Simien Mountains in the southern and northern parts of Ethiopia.

To identify the unique mandible, researchers used paleontological measurements, alongside advanced statistical methods. In the second stage of the study, extensive use of unique bio-climatic algorithms was made.

These models calculate environmental changes throughout a species' existence and the impact of climatic conditions on the necessary habitats for the wolf's survival in the highlands of Ethiopia.

"Our work shows that the Ethiopian wolf was on the brink of extinction several times during its million and a half years in Ethiopia, as a result of climate warming that reduced its viable habitats to higher regions where the conditions for its survival still remained," Prof. Hovers explained.

4 View gallery

Dr. Tegenu Gossa, Prof. Erella Hovers, and Prof. Bienvenido Martínez-Navarro

(Photo: Eduardo Pesao)

"These regions were geographically isolated, creating reproductive barriers that endangered the continued existence of the Ethiopian wolf. As the climate cooled, conditions led to the recovery of the necessary ecological system for the species' survival, allowing the wolves to return and expand their territories."

"The expansion of habitats and connectivity between its populations enabled the Ethiopian wolf to recover from the brink of extinction every time," she added. "The discovery from Melka Wakena, at an elevation of only 2,300 meters, likely represents a period of recovery."

According to researchers, the bio-climatic models which are based on previous findings also allow for predicting how future climate change might affect the Ethiopian wolf population, stressing that action must be taken to prevent the negative impact of climate change.

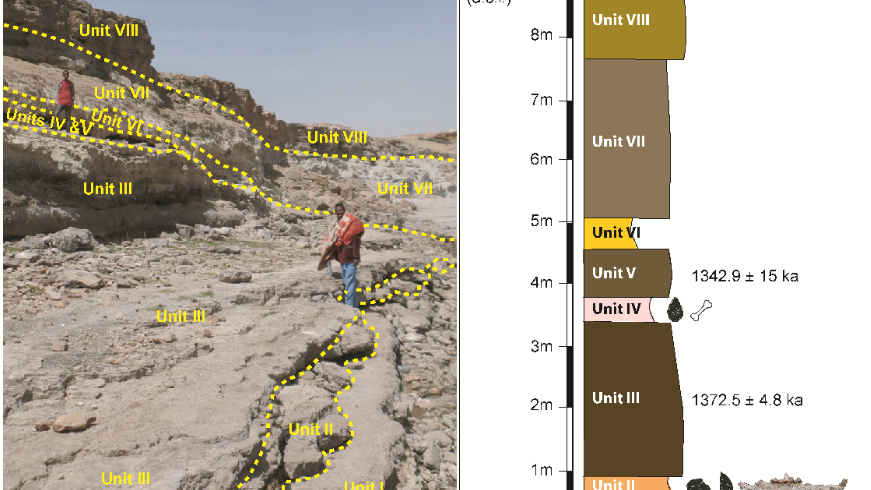

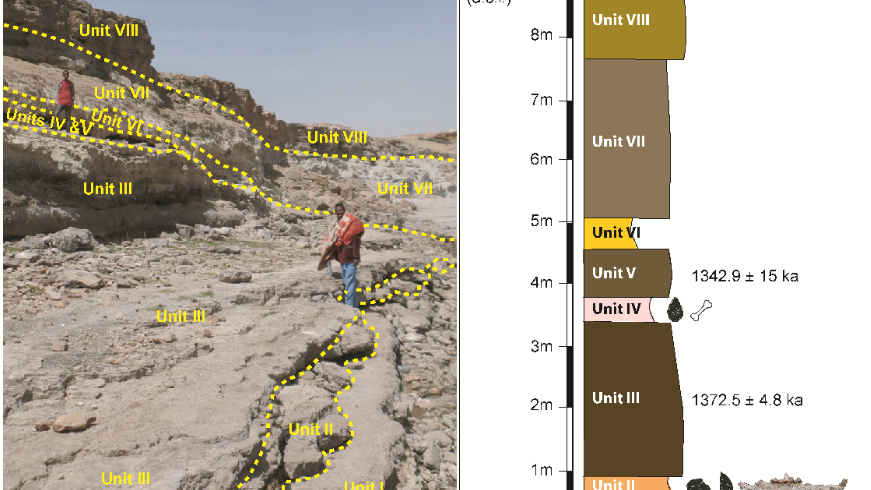

4 View gallery

The excavation area in Ethiopia and a graph showing land strata where the mandible was found

(Photo: Tegenu Gossa, Asfawossen Asrat)

"We were all aware of the threat of extinction facing the Ethiopian wolf before the study, but the predictions were more troubling than first thought. We found that global warming, combined with the expansion of agricultural areas, would result in the wolves' habitat being destroyed by 2080 by the most optimistic estimates," Prof. Hovers said.

"We hope that the research will raise further awareness of the urgent need to preserve the Ethiopian wolf's habitats."

The researchers emphasized that the significance of the Melka Wakena finding extends to the study of human prehistory as well. Most research in this field in East Africa focuses on the Great Rift Valley, which contains a rich collection of human fossils and archaeological sites dating back millions of years.

The study's findings reveal the need for further research into geological and ecological environments in an attempt to unravel Africa's environmental effects of human evolution.