Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The New Year festival in ancient Egypt, known as Wepet Renpet or "Opening of the Year," featured traditions that resonate even nowadays, such as exchanging gifts among friends and family to convey blessings for the year ahead. However, the celebration also included unique customs, like placing temple deity statues in sunlight for regeneration—a practice rooted in ancient beliefs. Sometimes, older statues were replaced with new ones as part of this ritual.

Interestingly, the timing of the festivities shifted over time, and the Egyptians occasionally celebrated the New Year twice or even three times in a single year. When the Egyptian calendar was established approximately 4,800 years ago, the festival coincided with the summer solstice (around June 21), marking the annual flooding of the Nile—a vital event for agricultural renewal. By the Middle Kingdom period (circa 2030–1640 BCE), however, the festival had moved to the winter solstice in December.

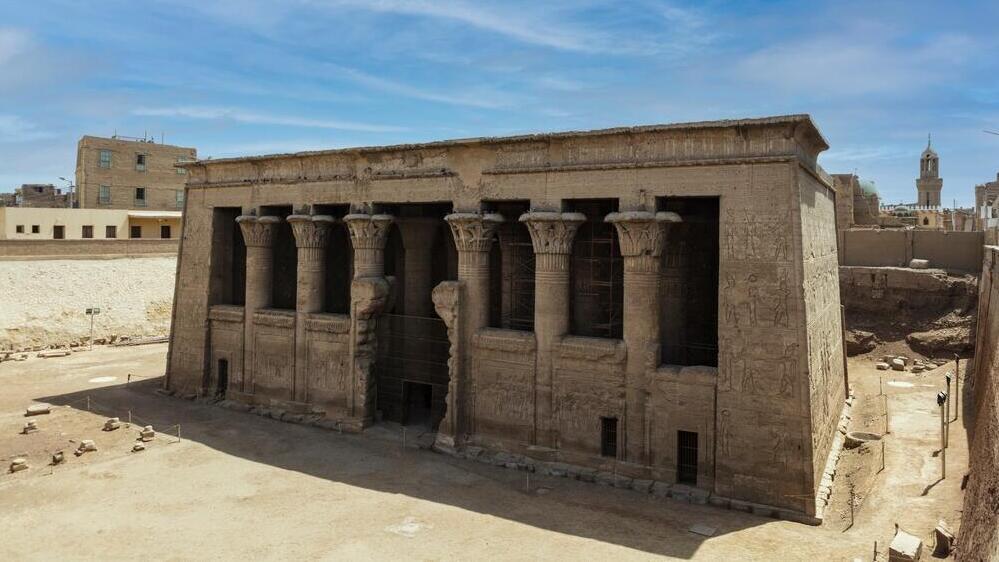

A unique discovery at the Temple of Khnum in Upper Egypt, about 55 kilometers south of Luxor, reveals that during the Roman occupation of Egypt (mid-1st to mid-3rd centuries CE), the New Year was celebrated three times a year.

According to Leo Depuydt, a professor of Egyptology at Brown University, the dates marked the first day of the Egyptian calendar year, the Roman emperor's birthday, and the heliacal rising of Sirius—a celestial event heralding the Nile's inundation and the summer solstice.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

Festivities often took place near iconic landmarks, including the Giza pyramids, adding grandeur to the occasion. Ancient tomb inscriptions describe lavish feasts and the exchange of gifts, symbolizing wishes for a prosperous year.

"The most famous object type relating to [the] new year is the 'new year flask', a lentoid vessel, typically made of faience," or glazed ceramic, John Baines, a professor emeritus of Egyptology at the University of Oxford, told Live Science. Some of these flasks are inscribed with messages wishing the recipient a joyful New Year. "The flasks are for liquids and have a rather small capacity — perhaps suitable for scented oils rather than drinks," Baines added.

3 View gallery

Inscriptions on this 2,600-year-old flask

(Photo: Theodore M. Davis Collection, Bequest of Theodore M. Davis, 1915; The Met)

One such vessel, displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, bears an inscription invoking blessings from the gods Montu (god of war) and Amun-Ra (mentioned in the Bible's Book of Jeremiah) for Pharaoh Amenhotep. It is believed to have held perfume, oil, or Nile water, serving as a symbolic gift during New Year celebrations.