Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

The discovery of the remains of six sheep in the elite burial grounds of Hierakonpolis, a central religious and political hub of Upper Egypt during the late Predynastic (ca. 3200–3100 BCE) and possibly the Early Dynastic period (ca. 3100–2686 BCE), has provided groundbreaking insights into the manipulation of animal morphology for ceremonial purposes. Archaeological analysis revealed deliberate alterations to the horns of these sheep, marking the earliest physical evidence of horn modification in animals –a practice previously known primarily through depictions of cattle in rock art.

Dr. Wim Van Neer of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels described the finding as "the earliest physical evidence of horn modification in animals." Although horn manipulation was documented in ancient rock art, this discovery confirms the practice extended to sheep, broadening understanding of symbolic animal manipulation in prehistoric Africa.

Sheep were introduced to Egypt from the Levant around the 6th millennium BCE and became a significant domesticated species by the 5th millennium BCE. Their cultural and religious importance grew over time, as evidenced by their depictions on pottery, carved reliefs and ceremonial items. By the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2055–1650 BCE), sheep species such as Ovis ammon, characterized by crescent-shaped horns, were integrated into Egyptian religious iconography, frequently associated with deities in the form of horned rams.

Burial context and horn modification

The burial site at Hierakonpolis, situated approximately 100 kilometers from Luxor, was the primary center of worship for the falcon god Horus. Elite burials in this cemetery were accompanied by a diverse array of wild and domesticated animals, including cattle, goats, crocodiles, ostriches, leopards, baboons, wild cats, elephants, bees, hippopotamuses and aurochs. Among these, six sheep were interred in tombs 54, 61 and 79, their remains providing compelling evidence of deliberate horn alteration.

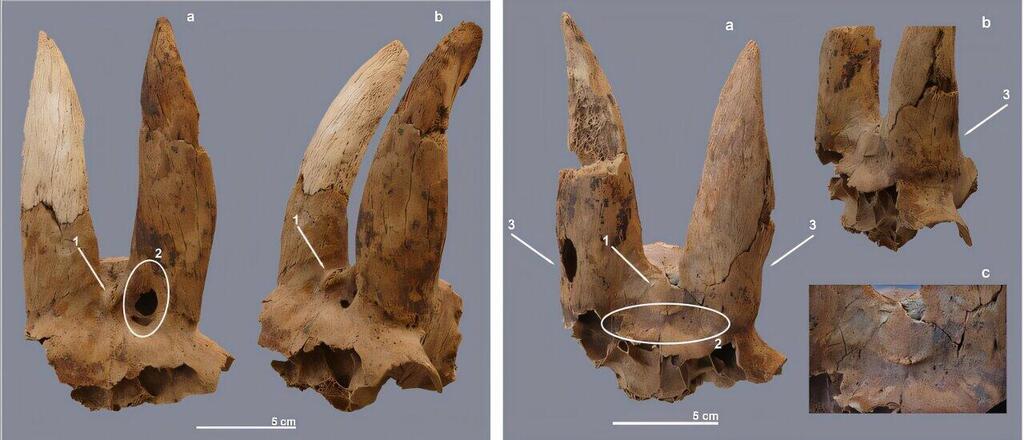

Analysis of sheep skulls showed that their horns had undergone significant modification, including complete removal in some cases. Furthermore, skeletal examinations revealed that several of the sheep had been castrated, as indicated by their elongated and larger bones compared to their non-castrated counterparts. The horn modifications were achieved through a method involving the intentional breaking and repositioning of the skull base at the horns, followed by binding the horns in place until the fractures healed. This process was evidenced by indentations at the horn bases, thin bone growth in the affected areas, and markings on the sides of the horn cores, likely caused by the bindings used during the healing process.

Van Neer noted that similar horn-modification techniques are still practiced today among agro-pastoralist communities in Africa, such as the Pokot in Kenya, who primarily apply the method to goats. In the context of Hierakonpolis, however, the manipulated sheep horns likely served symbolic purposes rather than practical ones. The elites of Hierakonpolis used these modifications as a means of asserting power and control over nature, transforming ordinary animals into extraordinary symbols of status and dominance.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

"It is unlikely these sheep were raised for consumption," Van Neer stated. "Their ages ranged from six to eight years, far exceeding the typical slaughter age of three years for sheep bred for food. These animals were purposefully altered to appear ‘special,’ reflecting the elite's ability to manipulate and dominate the natural world."

Implications and future research

This discovery provides key evidence of how animal modification practices played a role in the symbolic and ceremonial landscape of ancient Egypt. Van Neer and his team aim to explore whether similar horn modifications were applied to cattle or goats in future excavations at Hierakonpolis. Such research will further illuminate the ritualistic and symbolic practices of Egypt’s ancient elite, offering a deeper understanding of human-animal relationships during the formative periods of Egyptian civilization.