A recent study by Tel Aviv University challenges the prevailing scientific view that King Solomon’s copper mines harmed worker health in ancient times and continue to affect nearby residents today.

Researchers conducted geochemical surveys at copper production sites in the Timna Valley, dated to the 10th century BCE during the reigns of King David and King Solomon. They found that environmental pollution from ancient copper production was minimal and highly localized, posing no significant risk to residents in the past or present. Additionally, a review of previous studies revealed no evidence that ancient copper production caused global pollution.

The study, led by Prof. Erez Ben-Yosef, Dr. Omri Yagel, Willy Onderczyk, and Dr. Aharon Grinberg from Tel Aviv University’s Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures, was published in Scientific Reports, part of the Nature portfolio.

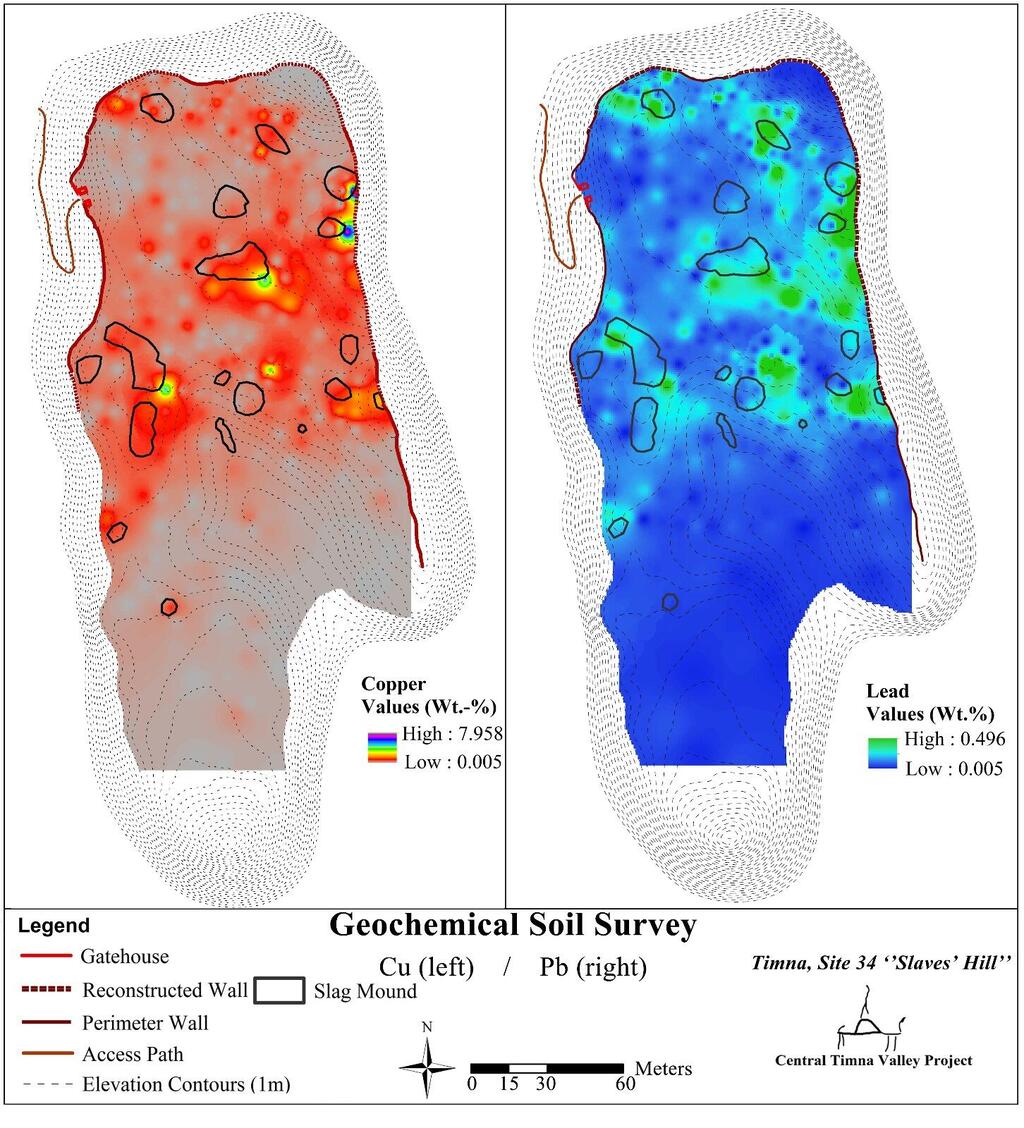

“We focused on two major copper production sites in the Timna Valley—one from the Iron Age, during the time of King Solomon, and an adjacent site that predates it by about 1,500 years,” said Prof. Ben-Yosef. “Our research was unprecedented in scope. We collected and chemically analyzed hundreds of soil samples from both sites, creating high-resolution maps of heavy metal distribution in the area.”

“Our findings reveal that pollution levels at the Timna copper mining sites are extremely low and confined to the vicinity of the ancient furnaces,” Ben-Yosef explained. “For example, lead concentrations—the primary pollutant in metal industries—drop to less than 200 parts per million just a few yards from the furnace. By comparison, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency defines safe levels in industrial environments as up to 1,200 parts per million and 200 parts per million for areas where children are present.”

The findings contradict previous studies, particularly those from the 1990s, which emphasized significant pollution from ancient copper industries. “We demonstrate that this is not true. Pollution in Timna is highly localized, and likely only affected those working directly at the furnaces who inhaled toxic fumes. Beyond the furnace, the soil is completely safe. Furthermore, the correlation we found between copper and lead concentrations in the soil indicates that the metals are ‘trapped’ within slag and other industrial waste, preventing their spread into the soil, plants, or humans,” the researchers explained.

The study also aligns with recent research conducted in Wadi Feynan, Jordan, which similarly recorded very low pollution levels. “Timna and Faynan are ideal research sites because they have not been disturbed by modern mining, as seen in Cyprus, and their arid conditions minimize metal leaching into the soil,” the researchers noted. “In Wadi Feynan, a team led by Prof. Yigal Erel from the Hebrew University analyzed skeletons of people who lived at the mining site during the Iron Age. Only three out of 36 skeletons showed traces of pollution in their teeth, while the rest were completely clean. Our findings in Timna present a similar picture.”

In addition to the geochemical survey, researchers conducted an extensive literature review, which found no evidence of global pollution during the pre-Roman period.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

“In the 1990s, there was a trend to label ancient copper production as the first instance of industrial pollution,” said Dr. Omri Yagel, a lead researcher. “Such claims attract headlines and research funding but unnecessarily project modern pollution issues onto the past. Moreover, there is a tendency in academic literature to use the term ‘pollution’ to describe any trace of ancient metallurgical activity, which has led to the mistaken assumption that metal industries were inherently destructive to humans from their inception—an idea that is simply not true.”

Dr. Yagel further noted, “When large-scale metal production became integral to human civilization, it was lead production—not necessarily other metals—that caused global pollution. A 1990s study claimed to have found copper residues in Greenland ice cores, supposedly transported there through the atmosphere from sites like Timna, but this claim has not been corroborated by any subsequent research. As modern researchers grappling with the effects of climate change, we have an inherent tendency to look for similar changes in the past. However, we must be careful not to conflate localized waste with regional or global environmental pollution.”