Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

A significant scientific discovery has emerged from one of the caves in the Jerusalem Hills. A research team comprising archaeologists and geologists from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv University has uncovered 50 cave pearls embedded with archaeological artifacts.

This remarkable find not only marks the largest discovery of its kind in the Middle East but also represents the first instance globally where cave pearls have been found enclosing man-made objects.

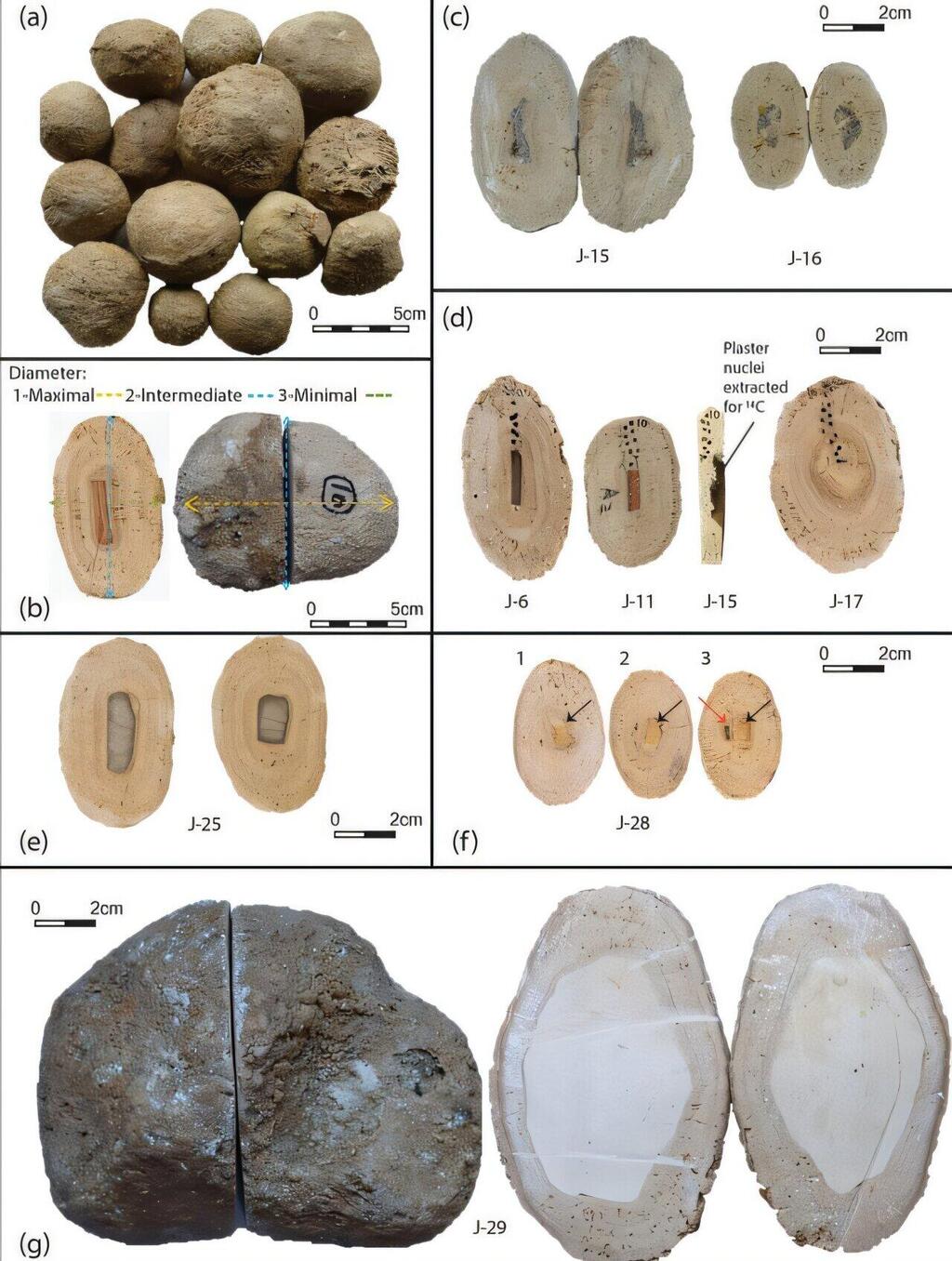

Cave pearls are a rare type of speleothem (cave deposit), similar to stalactites and stalagmites, but uniquely spherical in shape. While cave pearls are documented in caves worldwide, they are seldom found in Israel. Their diameters range from as small as 0.1 millimeters to as large as 12 inches. These formations develop around a central nucleus, which becomes coated over time in concentric layers of mineral deposits, such as calcite (calcium carbonate).

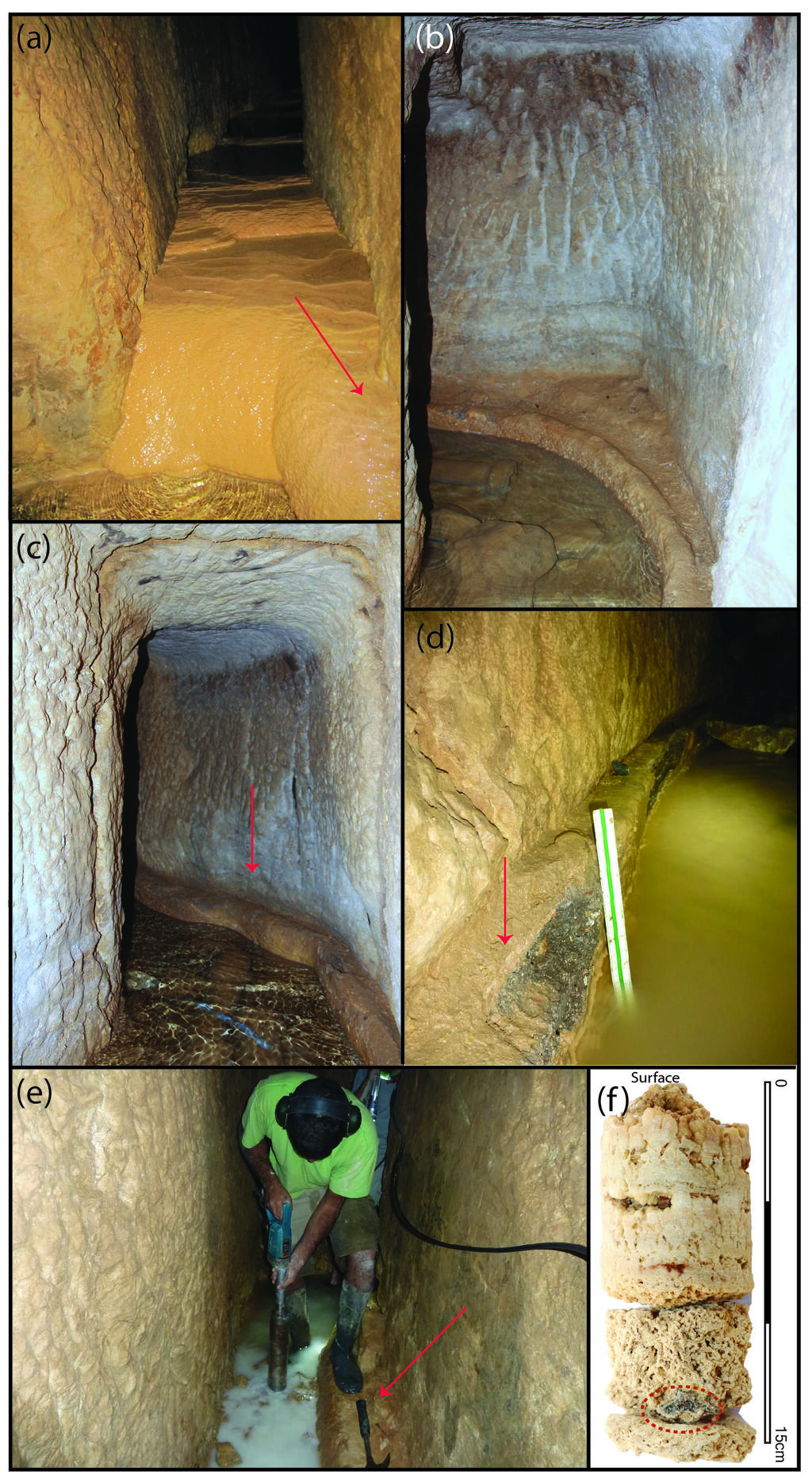

Unlike most speleothems, which typically require thousands of years to form, cave pearls can develop over several centuries under very specific conditions. These include a flat cave floor, a shallow pool of water, slow-moving or dripping water and gradual chemical changes in the environment over time.

The discovery, spearheaded by Dr. Azriel Yechezkael and his colleagues—including Dr. Yoav Vaknin, Shlomit Cooper-Fromkin, Dr. Uri Riv, Prof. Ron Shaar, Prof. Yuval Gadot and Prof. Amos Frumkin—represents the centerpiece of a study recently published in the journal Archaeometry.

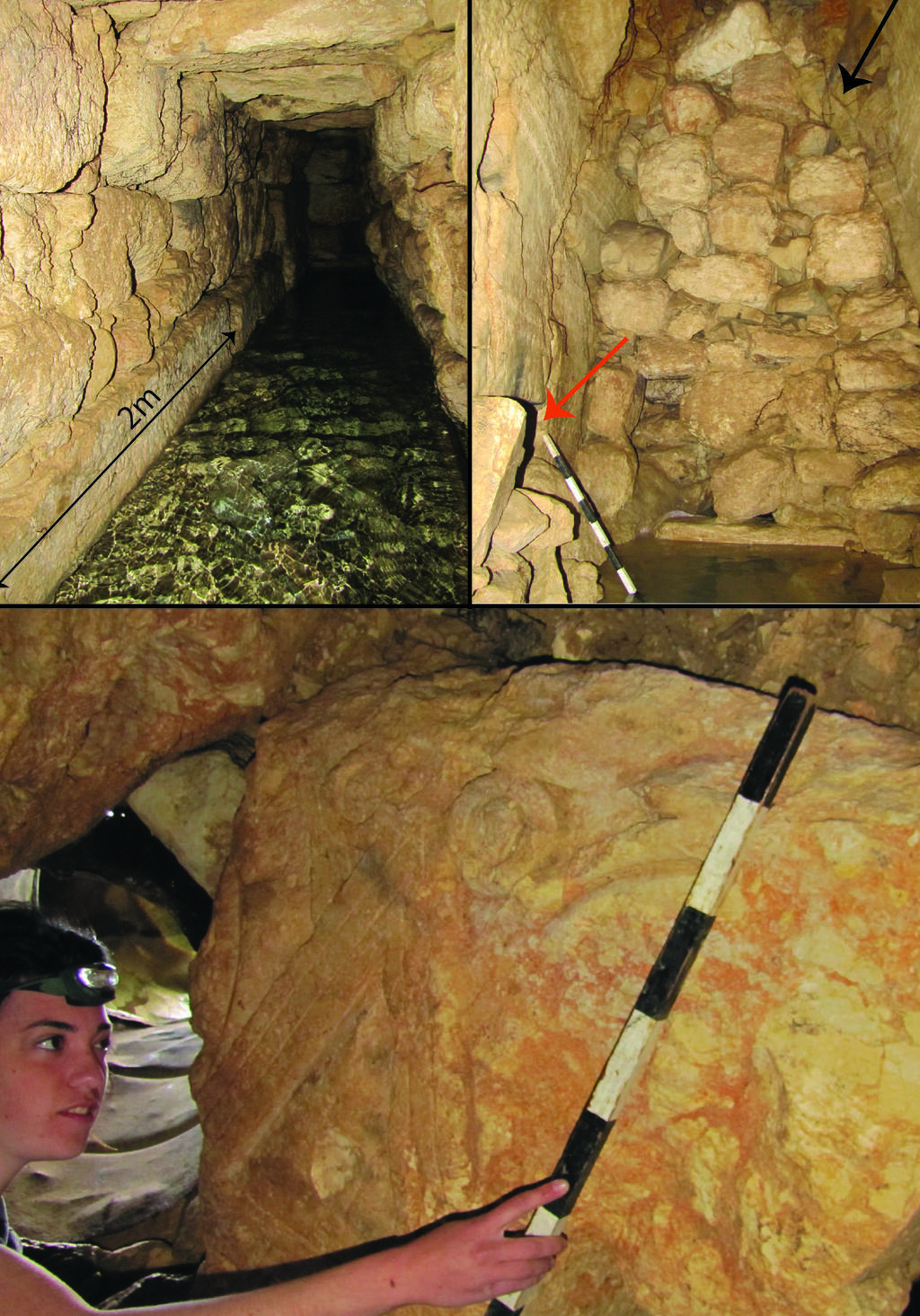

The cave pearls were located within the Ein Jawiza aqueduct, the longest aqueduct in the Jerusalem Hills, stretching 760 feet and characterized by its relatively winding structure compared to other aqueducts in the region.

“Our initial research focused on mapping and surveying archaeological evidence within the Ein Jawiza aqueduct. Cave pearls, a rare category of speleothems, were not something we expected to encounter. The discovery of these pearls, particularly those incorporating archaeological remains like pottery fragments, was entirely unexpected and of immense importance,” explains Dr. Yitzhak.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

“Of the 50 cave pearls we identified, 14 contained pottery fragments, while two others enclosed ancient plaster. These findings indicate that the pearls formed around anthropogenic nuclei, originating from antiquity.”

Artifacts encased in geological time

Analysis of the artifacts revealed that most of the pottery fragments date to the Hellenistic period (333–63 BCE), the Roman period (63 BCE–324 CE) and the Byzantine period (330–636 CE). One shard, however, was tentatively attributed to the Iron Age (1000–586 BCE). Their best efforts notwithstanding, researchers were unable to determine the precise types of vessels from which the pottery fragments originated.

“Despite our thorough analysis, we were unable to definitively identify the majority of the pottery fragments embedded in the cave pearls. However, it is clear that the fragments span multiple historical periods and were made from a variety of materials,” says Dr. Yitzhak.

Two pottery pieces, however, were successfully identified as fragments of ancient ceramic oil lamps. Furthermore, traces of a cobalt-based pigment—a material not naturally present in Israel—were detected on their surfaces. These observations led the researchers to conclude that the lamps were imported during the 2nd or 1st century BCE from regions such as Cyprus or Ephesus, a major Ionian city in Lydia (modern-day Turkey). “These lamps somehow ended up in the aqueduct, broke within it and over time, cave pearls formed around their fragments,” explains Dr. Yitzhak.

A window into the past

Based on both prior studies and current findings, it has been established that the Ein Jawiza aqueduct was first hewn during the Iron Age, likely as part of a royal estate situated near Jerusalem. The aqueduct was repeatedly visited, maintained and renovated throughout its history. Notably, during the Hellenistic period, significant restoration work was carried out, as evidenced by the pottery fragments and pieces of plaster embedded within two additional cave pearls. These were dated to the Hellenistic period using radiocarbon dating (C-14 analysis).

The aqueduct continued to serve the local population during the Roman and Byzantine periods before eventually being abandoned. “The story of the cave pearls provides a fascinating glimpse into how the springs surrounding Jerusalem were utilized by humans across millennia,” concludes Dr. Yitzhak.