"You also won't hear about how I fought all by myself with a knife between my teeth. It's simply a story about a boy who survived thanks to a lot of luck and resourcefulness."

Yoram (Wlodek) Sztykgold, 76, begins his account with a "warning", finding it difficult to understand why anyone would be interested in his personal story, doubting there is anyone who really wants to hear about those dark times at the Warsaw Ghetto.

- For further information and the full list of displaced children, visit the "Remember Me?" website at http://rememberme.ushmm.org/

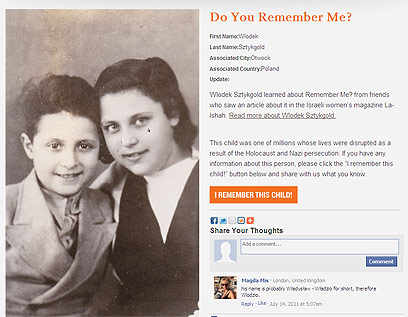

He recently received a phone call from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and was informed that a picture from the children's home where he recovered after the war appears in the "Remember Me" project album, which aims to locate 1,100 orphaned children who survived the Holocaust.

He was only three years old when the war began. His memories are the memories of a child – dramatic, surreal, unorganized.

He remembers the time his terrified grandfather emerged from the bathroom with his pants pulled down, the dog he had at the ghetto, which almost turned him in, the pot of hot soup that remained on the table in a house whose tenants disappeared – the pot which saved his life.

Bag with chocolate

Yoram was born in Warsaw in September 1936 to a wealthy traditional Jewish family. His father, Mistislav Moshe Josef, was an engineer and the owner of one of Europe's biggest gas street lamps factory and another that made hospital equipment.His grandfather worked in real estate and had a lot of property in Poland.

Yoram was Moshe and Helena's youngest child. His sister, Wanda, was four years older than him. The family lived in a large house with servants, nannies and a cook.

When the Nazis occupied Poland in 1939, the Sztykgold home was included in the area of Warsaw which was surrounded by a wall and turned into a ghetto.

The Nazis looted the expensive belongings and ordered the family to move into the kitchen. The rest of the huge house was turned into a laundry for the German army's underwear.

Yoram remembers the strong sanitization smell. He would spend days in the hideout his father created inside the room where bundles of linen would arrive, well packed, "like building blocks, in a German order." His father placed an oxygen tubule between the packages.

Yoram and his sister on museum website. 'I remember the prayers she taught me by heart'

The Germans robbed most of the Sztykgold family's money, and what they could take and hide bought life in the ghetto. With money and diamonds, father Moshe purchased food and certificates and used his connections outside the ghetto. He later smuggled his daughter Wanda out of the ghetto under a false identity, while little Yoram remained with his parents.

Wanda left, not before teaching her small brother all the Christian prayers by heart, as if she knew that one day he would need them.

"I am a grownup person today and I forget a lot of things, but I still remember those prayers by heart, word for word. It’s something that will never be erased.

"During the first few months, my mother Helena would cover my eyes when we walked on the street," Yoram recalls. "But you didn't have to see to understand what was going on.

"The ghetto was as noisy as a beehive, so crowded that you couldn't walk on the street, with a terrible stench. Sick people, children dying under the houses, flies everywhere. In the ghetto

"I never raised my head as I walked on the street. I always looked down so as not to see what was happening and not to meet the eyes of a German soldier."

He was always armed with a bag his mother had prepared for any scenario. "There were clothes in there and a bottle of wine and chocolate. Every time I returned home I would discover it was all stolen. People fought to survive."

'Hell on both sides and we're marching'

Yoram remembers how his grandparents' health and mental condition deteriorated. As two of the richest people in Warsaw, they suddenly found themselves penniless.

He remembers when his grandfather became the toilet cleaner at the factory built in his house, and how his grandmother continued to employ a cook even when there was nothing left to cook, until she died of grief.

Once, he recalls, as the Germans raided a block in the ghetto, his grandfather alarmingly jumped out of the bathroom with his pants pulled down, asking, "What happened?" while the family members were looking for him.

"It made us burst into laughter in the middle of all the tension. It was surreal," he remembers.

"The Nazis would raid a block or an entire area, remove the tenants from their homes, and we would hear the gunshots," Yoram recounts. "Every time they'd reach the area, we would jump from one house to another, through the rooftops or basements, and an informer would direct us where to run to.

"One night, after three days of not eating or drinking and basically turning into a corpse, I ran with my parents into one of the houses. A woman stood in the living room holding a hot pot of soup while her children sat around the table.

"I was exhausted and my parents knew I would not survive the night if I didn't put anything in my mouth. 'I have a sick child. Perhaps you could give him some soup?' my mother asked, but the woman in living room refused. 'Ma'am, would you give if you had any?' she responded.

"It was the first and only time I saw my mother cry. Suddenly we heard gunshots and began escaping again. For an hour we ran from place to place, jumping from one attic to another, until we somehow ended up in the same place.

"We entered the apartment again. This time it was empty. The woman and her children had disappeared – perhaps they were taken by the Germans or just ran away. The soup was standing there in the middle of the table and I remember it was still hot. My life was saved, and I still have no explanation why that happened."

Yoram with his sister and mother. 'She was always meticulously dressed' (Photo: Ben Kelmer)

The hunger, Yoram remembers, was intolerable. The German raids increased as the elimination of the ghetto drew near. In one of them, his mother broke down.

"My condition deteriorated because I didn't eat and didn't drink. Mother saw me fading away and gave up. She thought there was no use in running, we must get food even if we have to pay for it with our lives.

"We emerged from the hideout to the street. I looked down and we started marching. On both sides I heard the Germans with the dogs and the gunshots. And we were marching in the middle of the street, on the road, passing by everyone and certain that someone would open fire at any minute. But no one paid attention to us.

"Hell on both sides, people being shot and terrible screams, while we marched in the middle as if we were air. With every step, my heart went up to my throat and I sensed my parents' fear. It was a surreal situation. Minutes of walking felt like eternity.

"Four mounted policemen passed us, we felt the end was near, but they just kept on going, split to both sides while we marched between them toward the barrier, crossed the barrier and continued to a different part of the ghetto, where we got help."

Pedigree dog in poor neighborhood

Thanks to the money hidden by the father, the Sztykgold family members remained in the ghetto until its very last moments.

"At first there were 1,000 people on 1 meter (3.2 feet) in the ghetto until it became impossible to walk on the pavement. Then there were the raids and the number of people in the ghetto was reduced.

"When I left the ghetto, two weeks before the uprising, there was no one on the street anymore. There was a terrible silence. The only ones who remained in the ghetto were those who had a job. Father got me and mother fake certificates and we decided to escape, but at the last minute he announced he wouldn’t be joining us.

"Grandfather was a religious person and he thought that what was happening to us was a punishment from above, and that one can't escape such a punishment. He insisted on staying and father told us he couldn't leave his father and escape, even if he had a hideout waiting for him. Mother and I escaped on our own to a hiding place in one of Warsaw's poorest neighborhoods."

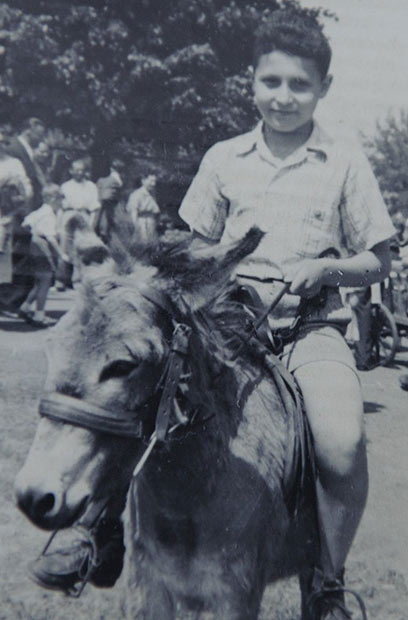

Yoram on a donkey. Immigrated to Israel at 21 (Photo: Ben Kelmer)

Yoram recalls the dog he had when the ghetto was established. "A beautiful pedigree dog which we had during our childhood, until one day my parents decided it was too much, that we cannot continue keeping a pet and feeding it while people are dying of hunger.

"Father bought poison and decided to put her to sleep. But three days later she suddenly came back to life. We were a religious family and we decided to try again. Father decided to smuggle her out and paid for the smuggling."

He never imagined he would see the dog again, several hours after arriving with his mother at a hideout outside the ghetto.

"Father must have made sure that the dog would be returned to me. I was so happy to see her again after everything I went through. It was a moment of joy.

"But less than half an hour later, Polish crooks smelled an opportunity. They immediately suspected that we were Jews, because it was impossible for anyone in such a poor neighborhood to have a well-groomed pedigree dog. They immediately asked for money so as not to hand us over to the Gestapo. We were forced to flee again."

On German officer's lap

The new hideout didn't last long either. While Yoram and his mother went out to catch a breath of fresh air, the Polish landlady who hid them went through their belongings and found fur and a pair of crocodile skin shoes the mother had smuggled.

"Until her very last day, mother always made sure she was meticulously dressed and had an impressive look," Yoram stresses. "What is this, ma'am?" the Polish woman shouted as the two returned from their short walk outside. "Where did you get such expensive stuff?"

The mother replied, "You want to know where it's from? It's a great story, I must tell you. But first I'll feed the child for a few minutes, and then I'll sit down and tell you."

Yoram's mother prepared a small meal for him, and when the Polish woman wasn't looking she packed a small bag and slipped outside.

Yoram will never forget that night. In the freezing cold the two hit the road, all alone in Warsaw's poor neighborhood. The next hiding place was at the other end of the Polish capital.

"The curfew was supposed to start in a short while and we knew there was no way we would make it unless we took a tram which only the Germans could use. Mother had nerves of iron. She told me some bedtime stories about the moon and stars and then she said, 'We're getting on the tram.' And I'm no idiot, I understood what that meant.

"We waited for it to become even darker and walked to the Germans' tram. We got on the streetcar, mother looked in and intentionally chose to sit in the only place facing two German officers. She sat down confidently and smiled, and they smiled back at her.

"I was so scared I couldn't talk. I wasn't scared I would utter nonsense; I was scared I would wet my pants and they would discover our trick.

"Mother was a beautiful woman and they fell for her charm. One of them courted her and the other reached out to me and put me on his lap. Throughout the journey he told me stories and showed me things through the window. At the end of the trip they kissed my mother's hand and we got off at the station."

Escape from toy shop

Yoram and his mother split. He was handed over to the Christian nanny who took care of him before the war. He remembers the day he arrived with her at the playground overlooking the ghetto.

He stood near the carousel, next to children and parents amusing themselves at the sight of the burning ghetto. He was forced to pretend that he was entertained, like everyone else, "by the sight of people falling off the rooftops like candles, from the gunshots and smoke. And that was when I knew that my father and grandfather were still in there."

Only seven years old, he already knew what the end of the world looked like.

Mother Helena hid at a Polish friend's house. Every two weeks she visited her son Yoram for several minutes at the nanny's house. One day, Yoram recalls, during a short walk, the nanny asked to tell Helena something.

"The nanny said that one of her friends who knew about me told her husband. And he asked to know where she was hiding me and where mother was hiding. He told her that if they turned us in they could secure their economic future forever. My mother was smart enough to understand the situation.

"She trusted the nanny, but was afraid she was being followed, so every minute was dangerous. She stopped outside a toy shop and asked the nanny to wait for us outside for a moment because she wanted to buy me a present.

"We entered the store and mother turned to the saleswoman and asked if there was another exit. The woman pointed to a different door. We escaped, leaving the nanny outside."

Last Jew in the world

Helena led Yoram to the last hideout, where he stayed until the end of the war, in the town of Żyrardów near Warsaw. He lived with a Christian family which got a lot of money for hiding him.

"I was pretty free to walk around there and get a breath of fresh air. They knew I was Jewish, but they got good money to watch me."

When the announcement was made about the end of the war, Yoram assumed he had been left alone in the world.

"I hadn't met even one Jew during that period and I assumed everyone had died, that i was the last Jew in the world. I was only nine, but I was concerned that I had been left all alone and didn't know what to do in the world."

Sztykgold in his home. 'I assumed everyone had died' (Photo: Ben Kelmer)

His mother Helena and sister Wanda managed to survive and unite on the other side of the Vistula River, which was liberated six months earlier by the Red Army. Half a year passed before the mother and sister could reach Żyrardów and visit Yoram.

They found him sick and weak, his body swollen from hunger and covered with wounds. It took him months to recover.

His mother volunteered in a Jewish children's home operated by the Joint organization in Otwock and brought him there. Alongside 130 children, many of them orphans left alone in the world, Yoram began a long rehabilitation process with his mother and sister by his side.

In 1949, the children's home was shut down and Yoram moved in with his mother, who had remarried a Jew who survived the Holocaust.

At the age of 21, Yoram left Poland and immigrated to Israel, where he met his sister Wanda who had made aliyah several years earlier. He enlisted with the IDF and then studied architecture. He married Liora and they have two children and six grandchildren.